In the 2002 book The Mind in the Cave, South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams explored a transitional episode in early human history: the urge to create art, to carve bone and soft stones, or smear a mix of fat and ochre on to rock walls. Why, asked Lewis-Williams, would early humans crawl along narrow shafts in the darkness to paint in underground spaces few would see? His (controversial) theory was that these early artists were shamanic figures; that their paintings related to visions experienced in altered states of mind, achieved perhaps through intoxicants and rhythmic ritual; and that the wall of the cave was considered a membrane between the spirit world and the realm of the living.

The Mind in the Cave is one of the guiding texts for Hollow Earth, which explores the cave in art and art in the cave. The Nottingham location is significant: the city sits above a network of more than 800 caves, carved into soft sandstone and used at various times as homes for the poor, tanneries and beer cellars.

The show is a lucky dip: sherds and archival material from the subterranean city share the gallery space with architectural models, museum paintings, sound art and oddities including a ceramic Japanese grenade. It’s not so much a show of contemporary art as a show about the kinds of things that interest contemporary artists: geology, deep time, peculiarities of nature, weird sounds, forgotten processes, early art.

“Cave” is not a term reserved for natural caverns. The fascinating California research organisation, The Centre for Land Use Interpretation, documents ways in which human construction frames, carves up and interacts with the dips and surfaces of the earth. Photographs from their archive show subterranean spaces used for storage and car parking. The pioneering French photographer known as Nadar leads us into the old catacombs under Paris. Pauline Oliveros and the Deep Listening Band bring us sounds from the Dan Harpole Cistern, a 200 million-gallon concrete container sunk underground near Seattle by the US military.

Hollow Earth progresses through a theoretical descent from the mouth of the cave to the depths. Allusions to Plato abound. Painting in the 1780s, Joseph Wright of Derby uses a cave’s mouth as a stony frame for a view over the Gulf of Salerno. His contemporaries were fascinated by the power manifested in natural phenomena: chasms and volcanoes that invited contemplation of inner Earth. Caragh Thuring’s 2018 painting Inferno offers a party of Grand Tourists in Georgian dress balanced on a lip of a crater, silhouetted against a golden plane of lava, a fantastical composition that reminds us of the enduring taste for danger, the thrill of threat.

Santu Mofokeng’s photo series Chasing Shadows shows worshippers at cave complexes in central South Africa. Uncanny in candlelight, caverns offer numinous space for ritual. As marginal spaces between the built world and the wilds, caves feel like sites beyond regulation, a world apart from organised religion, connecting worshippers to something ancient and ancestral.

A highlight is Lydia Ourahmane’s 2022 film Tassili, shot among otherworldly rock formations of the Tassili n’Ajjer national park on the Algerian-Libyan border. A site of human shelter for millennia, the rock walls of Tassili carry art dating back 12,000 years – including what appear to be demons and aliens – and which charts the progressive desertification of the region. In her notes for the show, Ourahmane points out the region’s growing inaccessibility. When she first visited there had been three water sources: when she travelled to Tassili with her team to make the film, only one remained. The site is the star here, but an exciting experimental soundtrack composed by musicians Nicolás Jaar, Felicita, Yawning Portal and Sega Bodega connect contemporary rhythms to ancient ritual.

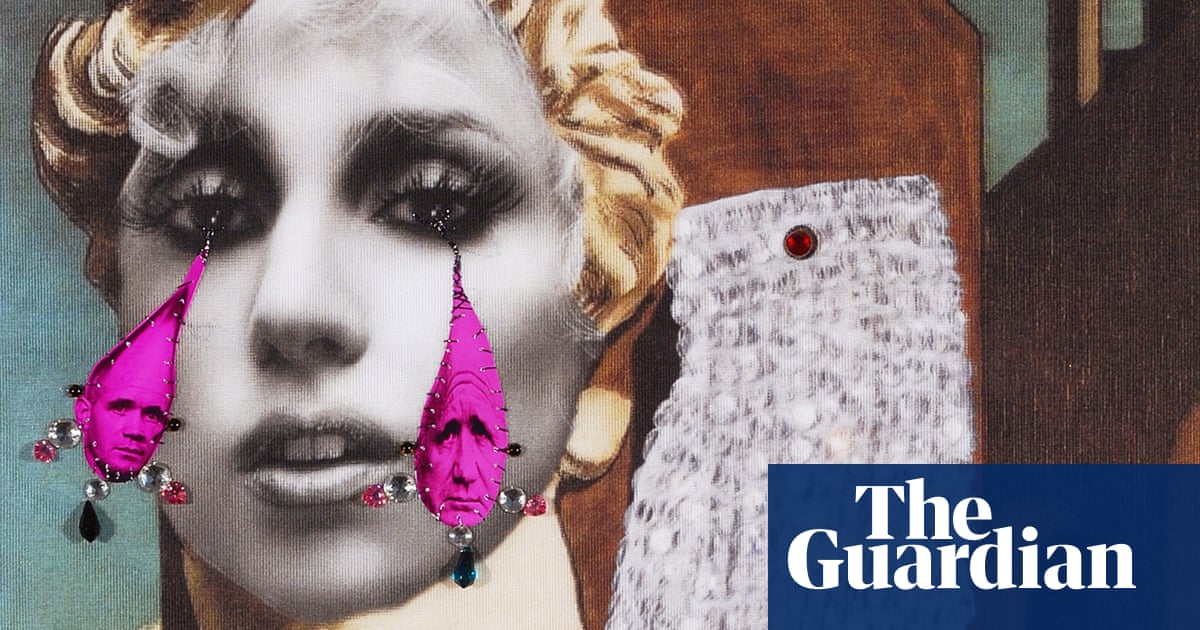

Goshka Macuga’s witty 1999/2022 installation Cave reimagines the cavern as a museum for the modern era. In past iterations she has shown works by artist contemporaries, and objects from a museum archive. Here, a tunnel lined with crumpled brown paper houses wonkily displayed sculptures and paintings. In the centre is a miniature spaceship, apparently poised to launch through a retractable roof, Tracy Island-style.

Some of the most exciting work comes from artists engaging with distant forebears. Chioma Ebinama’s glorious Tibetan scroll-like paintings feel ancient, but slyly insert (otherwise absent) female figures into an 11th-century narrative of meditation and enlightenment.

To complete the vibe, Emma McCormick Goodhart has worked with a perfumer to reproduce the aroma of one of the Lascaux caves (the base notes are “wet clay and moonmilks” apparently). Enveloped in the cavey smell, the cosseting darkness and the pulsing music, you’d be forgiven for wanting to daub the gallery walls.

Hollow Earth: Art Caves & The Subterranean Imaginary is on at Nottingham Contemporary until 22 January 2023, then touring