In the early days of modern US pop music, female artists struggled to achieve the recognition of their male counterparts. So a new marketing trope emerged. It labelled jazz trumpeter Ernestine “Tiny” Davis as “the female Louis Armstrong”. Big band drummer Viola Smith became “the female Gene Krupa”. And the rockabilly pianist Alice Faye Perkins turned into Laura Lee Perkins, “the female Jerry Lee Lewis”.

But no artist inspired more female counterparts than the king of rock’n’roll. “There seemed to be a special drive to find a ‘female Elvis’ at several different record labels” says Leah Branstetter, a musicologist specialising in women in the first wave of rock’n’roll.

Among the many female Elvis Presleys there was only one who took the role literally. She slicked back her hair and styled it to give the effect of sideburns. She wore a low-slung guitar and became known for her uninhibited gyrations. And she assumed the stage name Alis Lesley so that only a couple of consonants separated her from the king. “I’m not aware of anyone who stuck to the ‘female Elvis’ bit quite like Alis Lesley,” says Branstetter.

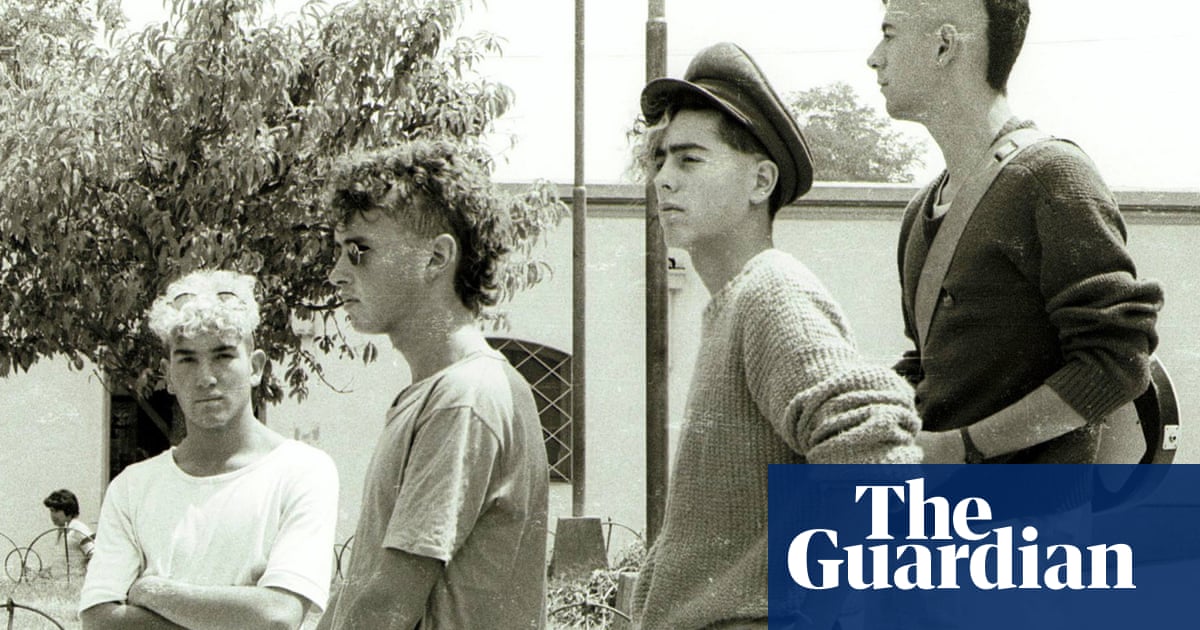

While this approach brought Lesley some early success, her music career was short-lived. In 1959, at the age of 21, she left rock’n’roll behind. In the decades since, she has reportedly given just one interview. But, this year, Lesley was unexpectedly thrust back in the spotlight when she was revealed as the figure between Little Richard and Eddie Cochran on the cover of Bob Dylan’s new book, his first since 2004’s Chronicles: Volume One. Due in November, The Philosophy of Modern Song comprises 60 essays by Dylan on songs by other artists. The press release states that the book’s images have been “carefully curated”, inviting speculation as to why such an obscure artist as Lesley should have been chosen for the cover. Dylan, naturally, hasn’t commented.

Lesley got her start during Dylan’s formative years, so it’s possible that he may have been familiar with her, or even seen her passing through on the US touring circuit. She started out playing local nightclubs in a band called the Arizona Stringdusters in her home town of Phoenix. But her big break came in 1956 when she was invited to perform with bandleader Buddy Morrow. During an uninhibited rendition of Blue Suede Shoes, Lesley kicked off her shoes. The audience loved it and touring schedules were soon drawn up.

When Lesley performed in Las Vegas, Presley himself came to see her. He was reportedly impressed enough to recommend her for Little Richard’s forthcoming tour of Australia. The press began to take interest and declared that Lesley was “destined for long-term stardom”.

She released her first single in April 1957. Unfortunately, it would also be her last. Titled Heartbreak Harry, the record invited an obvious association with Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel, the bestselling single of the previous year. And while it received a favourable notice in trade magazine Cashbox, which called it “a terrific rock and roller”, the record failed to capture the public’s attention. By the time of the Australia tour with Little Richard a few months later, Lesley was already talking about quitting. “I’m not growing old in show business,” she told one reporter. “I’m thinking of the future.”

Other press coverage at the time alluded to her ambitions to write original material. Branstetter posits that this may have been a factor behind her disillusionment with the music business. “I think interviews with Alis Lesley show that she had a lot of ambition and that she had no intention of being the ‘female Elvis’ for ever. Perhaps the desire to write her own songs had something to do with that.”

When Lesley returned to the US she spoke even more candidly to the press. “I don’t particularly like show business,” she said. “But I can’t get out of my contracts for at least two more years.”

Over those next two years, she continued touring, performing a setlist peppered with Elvis hits – Hound Dog, Don’t Be Cruel and Blue Suede Shoes. She once shared the bill with Bobby Darin just as he was emerging into superstardom. And she seems to have been particularly popular in Quebec, Canada, visiting four times.

Lesley’s last attempt at a big break came late in 1959, when she recorded at Sun Studio – the very place where Elvis got his start. She cut six takes of the Charlie Rich song Handsome Man, but the deal didn’t go through. By the end of the year, Lesley had left the music scene for good.

The little we know of Lesley’s subsequent years comes from a single interview she gave to researcher Will Beard, excerpts of which were published by Hank Davis in the CD box set Memphis Belles: The Women of Sun Records. According to what she told him, Lesley returned home to care for her ailing mother. She earned a degree in education and worked closely with Native American communities as an educator and missionary. She spent her retirement “travelling around the world” and survived cancer in the 90s.

Lesley is now 84 and still living in Phoenix. And though she keeps out of the public eye, she recalls her music career fondly: after local journalist Ed Masley wrote about her in the Arizona Republic earlier this year, she wrote to him expressing her gratitude at being remembered and said she looked forward to the publication of Dylan’s book.

But, if Lesley has any theories as to why Dylan might have chosen her image for the cover, she hasn’t shared them yet.

Laura Tenschert, the host of the Definitely Dylan podcast who also sits on the board of the University of Tulsa Institute for Bob Dylan Studies, suggests that the image choice may not be about Lesley, but the combination of her alongside Little Richard and Cochran. “It seems like an acknowledgment of the diverse roots of modern American music,” she says.

She argues that “the three figures on the cover could be seen to represent different sides of Dylan’s own musical identity”. For Lesley, that representation might be in her assumption of another artist’s persona. Dylan took a similar approach in his early years, modelling himself on folk singer Woody Guthrie. But where Dylan was able to move beyond this and carve out his own identity, Lesley’s ambitions seem to have been entirely overshadowed by the “female Elvis” persona.

More broadly, the cover could be seen as an acknowledgment of the ephemeral nature of what Dylan calls “modern song”. Branstetter notes that all three artists on the cover had left the music scene “within a matter of two years or so of this photograph being taken”. Little Richard quit to join the ministry. Lesley traded in her guitar for a quieter life. And Cochran died in a car accident at the age of 21.

Dylan’s career has enjoyed much greater longevity. But he has always been aware of the fleeting nature of popular music. When asked how he felt about Rolling Stone magazine declaring his song Like a Rolling Stone to be the greatest of all time, he merely shrugged and responded: “Who’s to say how long that’s going to last?” (Indeed, in a recent update Rolling Stone demoted Dylan’s song to fourth greatest.)

Perhaps some of Dylan’s attitude is encapsulated in that cover image. The faces of Alis Lesley, Little Richard and Eddie Cochran smile out at us, full of youth and hope, at the centre of a musical revolution – little knowing that it would all be over before any of them could have expected. Dylan pays homage and tribute to these rock’n’roll pioneers who came before him. But, perhaps, he also acknowledges how brief their moment was – how “the present now will later be past” and today’s “modern song” is tomorrow’s history.