When the first full-length play by an Indigenous Australian to be professionally produced premiered in Redfern in 1975, its writer, Robert Merritt, sat chained in the audience to two police escorts for the entire performance.

When the play ended, to thunderous applause, Merritt walked to the stage, throwing his arms in the air, as well as the arms of his two burly security escorts. He was still handcuffed to each of them.

Merritt wrote The Cake Man in 1974 in a writing workshop while an inmate at Bathurst jail and was granted release for the night to see the premiere, held at the Black Theatre Arts and Cultural Centre in Cope Street, Redfern, where the short-lived but culturally powerful National Black Theatre found its second home, having begun in 1972 in a nearby terraced house.

The play was based on the lives of Merritt’s parents and tells the story of an Aboriginal family struggling to live on a mission: Sweet William, his Bible-loving wife Ruby and their son, Pumpkinhead.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of the National Black Theatre, Merritt’s niece, the Wiradjuri and Yuin actor Angeline Penrith, will perform a monologue from The Cake Man at the Party, Protest, Remember event at Carriageworks this Saturday, held in Eveleigh, having grown up nearby in Redfern.

Her late uncle’s seminal play has deep personal significance, being about her grandparents, and emerging from an era when a new Black civil rights consciousness fed Indigenous empowerment in law, medicine, housing, land rights and the arts in Australia.

“The Cake Man has been a huge influence in my life,” Penrith says. “The play gives me a snapshot into life I wasn’t privy to, being born in 1982; the icing on the cake is it was about my family.

“I am a child of the revolution, of the people who did it their way: all Black leadership, Black actors. For me, that was the ultimate way of creating, out of [political] resistance.”

Her uncle Bob was a “rebel” but he “wasn’t looked on as a criminal in Aboriginal communities”, Penrith says. “He was looked on as another brother boy, another community person.” Merritt went on to establish the Eora Centre for the Visual and Performing Arts in Redfern in 1984.

At the Party, Protest, Remember event, Penrith will also read from the provocatively titled Here Comes the Nigger, written by the late Bundjalung playwright Gerry Bostock and staged at the National Black Theatre in 1976.

The National Black Theatre grew out of street theatre staged during protests over land rights and mining on Aboriginal sacred sights. It was a visit by Palm Island-born actor and playwright Bob Maza to the National Black Theatre in Harlem in 1970 that opened his eyes to Black theatre’s potential.

Police brutality and regular arrests and raids on the Empress hotel in Redfern had spurred many Aboriginal people into activism and in turn the arts. Prof Marcia Langton, now chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne, recalled in Darlene Johnson’s 2014 documentary The Redfern Story (which will be screened as part of Party, Protest, Remember), the local police cells “were called the abattoirs. The cells were covered with Aboriginal blood.”

The theatre began in a rented two-storey sandstone terrace in Regent Street, Redfern, which became a gathering place of debate, music and political strategising, a hub for the local Black caucus running Australia’s first Aboriginal-controlled legal and medical services, established in Redfern in 1970 and 1971 respectively.

Penrith’s mother, elder Aunty Bronwyn Penrith, recalls landing in Redfern from Griffith with her suitcases in 1970, not knowing anybody, seeking job opportunities in a suburb where some 20,000 Aboriginal people were living, mostly in poverty. Aunty Bronwyn soon met Indigenous activists such as Paul and Isabel Coe, Gary Foley and Gary Williams, whose “coming together was a very powerful spearpoint of the movement”, she says.

She was persuaded to take part in street theatre during protests and went to small discussion groups held by a young Indigenous mob educating themselves with books about the United States civil rights movement. Together, they saw politics and art as inseparable. Aunty Bronwyn was also part of the activism at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy set up opposite old Parliament House in 1972.

The National Black Theatre’s earliest success was its Basically Black revue skits, performed at Nimrod Theatre in Kings Cross, which were then commissioned as a short-lived ABC TV pilot series in 1973 – but discontinued when considered “too political and provocative” by the national broadcaster.

The theatre wound up in 1977 due to a lack of government funding. Today, Australia has Indigenous-controlled arts companies such as Ilbijerri Theatre Company in Melbourne, directed by Bob Maza’s daughter Rachael Maza, and the Bangarra Dance Theatre, but Brownyn and Angeline Penrith say Indigenous Australians “absolutely” still should have a national theatre.

“Today I’d like to see a National Black Theatre enable people to come together and guide what happens in Black theatre,” Aunty Bronwyn says.

“In these days of truth-telling, it’s become even more important that we can draw on the early days of Black theatre. The honesty and rawness of theatre. This had no filters.”

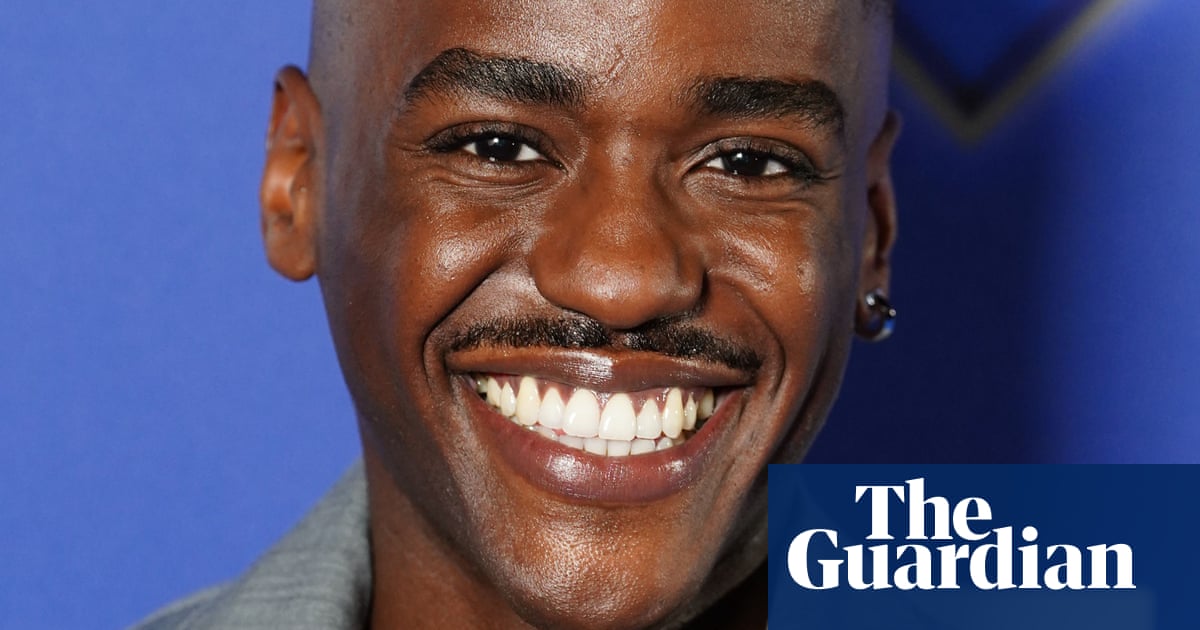

Thomas Mayor, a Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man and Uluru Statement from the Heart campaigner, says “consciousness and courage comes very much from the arts as a driving force … of protest – I don’t think you can have one without the other”.

At this weekend’s Party, Protest, Remember event – which will also feature live music, DJ sets, weaving circles, performances by Jannawi Dance Clan and a drag stage hosted by Nana Miss Koori – Mayor will lead a citizens’ assembly for discussions, questions and answers about a constitutionally enshrined First Nations voice to parliament, ahead of the federal government’s referendum ballot, expected sometime between July 2023 and the end of the June 2024.

Mayor, who is also the Maritime Union of Australia’s national Indigenous officer, was entrusted to carry the 1.6 by 1.8 metre “sacred” Uluru Statement from the Heart canvas around Australia, “rolled up in a patched-together postal tube”, rolling it out for groups from cities through to remote communities to read.

“I am optimistic [for a successful yes vote] because of an obvious change of sentiment among the Australian people, to want to acknowledge that there is a dark history in this country and the way things are,” Mayor says.

“It’s not going to come without hard work and the sort of sacrifice our elders had to do to see the 1967 referendum succeed, but I do believe in my people, and there is goodwill across broader Australia.”

Aunty Bronwyn, however, says she doesn’t have a lot of faith in the voice to parliament proposal. “I’ve seen a lot of forms of this, so we’ll just see how it goes,” she says. “We’re way past the advisory stage. We need to be there with proper treaty and sovereignty.”