In January 2021, 18 months after a sticky divorce, I bought a house. I bought it partly because I could – my ex-wife and I had got lucky on the property ladder and walked away with enough money for a deposit each. But also, I bought it because I was desperate. With shared custody of our two-year-old daughter, I needed a place where she could be happy and where I could get back on my feet.

It wasn’t my dream home. The bay window had been replaced by a PVC box, the walls were wonky, the windows were draughty and the pipes groaned whenever I turned on the heating. It was freezing in winter and, I would learn, had a slug problem in summer. On a road in Walthamstow, north-east London, lined by Victorian bay-windowed terraces, mine stood out like a cracked tooth.

The divorce had hurt. After a decade together, five of them married, there had been no emotional or physical abuse, no infidelity; love just curdled. Plus there’s nothing like new parenthood to expose cracks in a marriage. “Daddy,” our daughter said one bedtime soon after the separation, “when I’m a baby again, will you and Mummy live together like you did when I was a baby before?” Turns out explaining to a toddler that time runs inexorably in one direction is far easier than explaining why two grownups can no longer share a home.

So the first time I turned the key on that grey January day, at the height of the pandemic, I felt elated. This house represented a new future for us both. I never once thought about its past.

“The first thing you do when you move into a new house is wipe all memory of the previous owners,” my brother, Nick, said a few weeks later. “And we can start with that disgusting carpet in the front bedroom.” The carpet was a browny grey, like rat’s fur. And it clung stubbornly to the floor. But with a crowbar and brute force, it slowly began to submit. Suddenly, Nick stopped yanking and stood up. “There’s something wrong with your boards.”

The more we pulled, the more we saw it – an amorphous black patch, about the size of a double bed, in the centre of the room. Some of the boards appeared chewed up and peppered by flecks of white and grey where there had obviously been some kind of fire. My homebuyer’s survey had mentioned nothing of this. While the damage was cosmetic, it didn’t take a joiner to see the boards needed replacing.

Most fires start in kitchens, not bedrooms. This one had obviously been small, on the exact spot where a bed must once have been, and where my bed was now. The next morning, I looked back at all the images ever taken of the house on Google Street View. One, from August 2008, showed the house just as it is now except for corrugated iron sheets where the windows should have been. Above the window frames sooty marks curled up the front of the house like eyelashes. The gutters were melted, mangled, and the facade’s white render was peeling.

I sent a freedom of information request to the London fire brigade, asking for a list of every call-out to my street in the past 20 years. Since 2000, almost a third of the 20 calls to which firefighters had responded were to one address: mine. Four “malicious false alarms” and two “primary fires”. Stranger still, five of those incidents (including both fires) had taken place within a seven-month period, between February and September 2008. The fire brigade wouldn’t tell me whether anyone had died, or been hurt, and the police wouldn’t help. A trawl of the local paper from the time yielded nothing.

I went outside and looked up at the house. It had clearly been repaired. Two doors down, I saw Jackie – who has lived on the street for 20 years – smoking on her front step. I asked if she knew anything about the fires. “Oh yeah, we all used to call yours The Fire House,” she said. Jackie also told me she remembered the man who had lived there at the time; he used to light fires in the bedroom, then sit on the wall opposite to wait for the fire brigade. “One fire was so bad,” she said, “I thought it was going to take our house down with it.”

She tapped ash into a flowerpot. “Of course, he’s in prison now for raping those women. He murdered one in the playground round the corner. The papers called him the E17 Night Stalker.”

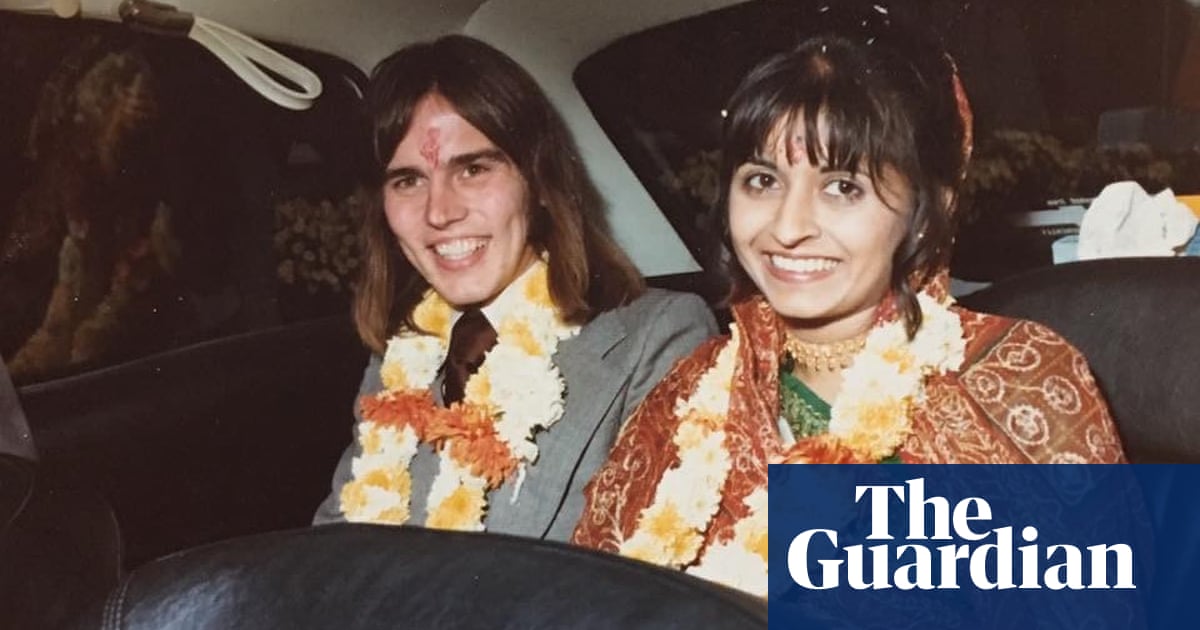

When Aman Vyas came to London from India, he was 24. A university graduate whose father had been a teacher, he moved into this house in 2008, found a job at a dry cleaner’s and a girlfriend about his age. He also had a terrible secret. A jury at Croydon crown court heard that, between 24 March and 30 May 2009, he had attacked four women between the ages of 32 and 59. Always at night, always near his home: in a graveyard, an alleyway and a woman’s own home, where he had forced entry. His last victim was a 35-year-old widow named Michelle Samaraweera. He spotted her at 1am in the local supermarket, where she had popped in to buy milk, and he killed her in the children’s playground 50 yards up the street.

Police had DNA but initially found no match. In what became one of the largest manhunts in British police history, they swab-tested more than 1,000 local men, posted leaflets through doors and put out an appeal on the BBC’s Crimewatch. Eventually, the investigation yielded a name. By then, Vyas had got wind of the appeal and bought a one-way ticket to India, where he hoped to avoid extradition.

Meanwhile, Samaraweera’s family, and those of Vyas’s other victims, faced an unimaginable wait for justice. Walthamstow MP Stella Creasy led a campaign to bring him back. Local women held a march. It was only in 2019, after a 10-year extradition battle with Indian authorities, that British detectives brought him home to face trial.

“Aman Vyas has had over 11 years to come clean and admit to raping and murdering my sister, and even longer to admit to all the other heinous crimes committed against the other innocent victims,” Samaraweera’s sister told the court during his trial. “Instead, he has lied and fabricated stories for his own benefit. He will never understand what he put my mother, sisters, children, loved ones, friends and myself through.”

Summing up, the judge told him: “You have shown neither compassion nor remorse for your victims throughout your trial, putting those who were alive, and could remember events, through the ordeal of reliving events, whilst you continued to protest your innocence to the bitter end, concocting ever more fanciful versions of events as you struggled to explain away the weight of the evidence against you.” Vyas was jailed for life, with a minimum term of 37 years before being considered for parole.

As far as I know, Vyas committed none of his crimes inside the house, and nobody died here, at least not at his hands. But it is where he lived. Where he came home, cleaned himself up. Some of my neighbours even remember him. “Kept himself to himself,” Jackie’s partner Mike told me. “Not rude, but not friendly. I don’t think I ever heard him speak. He always looked at the ground when he walked past.”

All houses have histories. But how much thought do we give to what happened in them before we moved in? Like most people, I treated this house’s past like the junk folder in my email: you know there might be bad stuff in there, but so long as you never open it, it can’t do any harm.

That evening, after I’d finished reading the court report, I found myself peering into corners of the room to check the shadows were still where they should be. For a time, I became darkly obsessed with my house as the staging area for Vyas’s depravity. It became wrapped in the horror of what he did.

Time passed. I ripped up the charred boards and replaced them with new ones. My daughter started primary school at the end of our street. Yet, walking around the house, my unease remained. When I was on my own, I began to imagine him here. Did that third step creak for him as he went upstairs to bed? Did the front door key stick for him when he let himself in? Some evenings, as my daughter slept, I’d find myself ghoulishly imagining what he did when he came home after committing the crimes.

I never found out why he started the fires. They don’t fit the timeline of the crimes for which he was convicted – the last one took place a few months before the first rape. My guess is that it made him feel powerful. But that’s all conjecture.

In 2010 the novelist Harriet Evans bought a new home with her partner on Danbury Street, north London. They moved in and unpacked their boxes, but for Evans, something didn’t feel right. The place was always cold, none of the door handles worked and there was a mouse infestation they couldn’t fix. “It just had a vibe,” Evans says. “Then I discovered we were the fifth people to buy it in 10 years.” Evans Googled the address. “It was all over the internet,” she recalls. “The last thing you want is to see your new home described as one of the most notorious houses in north London.”

In 1902, a woman named Annie Walters had murdered two babies in a room she’d been renting at the property. She had been engaged in “baby farming” – demanding payment from desperate single mothers in return for giving their unwanted newborns a better life.

“I was trying to have a baby at the time and the idea that these babies had been murdered there was incredibly painful,” Evans says. “For a while I was freaked out by it, driven in part by the fact that I’d recently left my job to write full-time and was in a state of high anxiety and depression,so it wasn’t a great time in my life anyway.”

“Houses with horrible histories can be challenging to sell,” says estate agent Reuben John, sales director at M&M Properties in north London. “Some people really care and won’t go near it; others pretend they care just to get a discount. But the truth is, a nice property will always sell, especially in London.”

Nobody knows this better than John. In 2015, he sold 23D Cranley Gardens, in Muswell Hill, to an asset management company for £285,000. It was in this flat that, in 1982 and 1983, Dennis Nilsen murdered the last three of his 15 young male victims, chopping up their bodies and flushing parts down the toilet.

The flat’s current tenants declined to be interviewed for this article, but John remembers the sale well. “The moment I walked in, I picked up a really creepy feel,” he says. “I have often wondered if this was because I already knew what had happened there, or because there really was a dark energy to that place.”

Unlike my home, 23D Cranley Gardens is such a famous address that John chose to disclose the property’s past to prospective buyers. “A lot of people were very open-minded until they walked through the front door. Some actually said they felt an evil presence, walked straight out and refused to go back in.”

Laura Bamber lived in a notorious property from the age of 13. In the 1990s, her parents moved her and her two sisters into a large Georgian house in the Kent countryside. They soon learned that the wife of the previous owner had killed herself in the basement two decades earlier. “Local rumours were that her husband was abusive and used to lock her down there,” she says. “We even found a lilac dress of hers in a cupboard in the attic.”

While Bamber says she enjoyed a happy childhood there, some of the rooms had “oppressive vibes, a real Miss Havisham feel. I’m not superstitious, but the rooms where the previous owners spent most of their time always had a weird smell. A lingering, foreign smell.”

The question of whether houses soak up “vibes”, as wallpaper absorbs cigarette smoke, has troubled humans for centuries. The science of this phenomenon is the study of “emotional residue” – which explores whether feelings hang around in a physical environment after the residents have left. Scientists have even proved that tears and sweat glands pump out “chemosignals” other people detect and physically respond to, not only in the moment but even after the source has gone.

After I told friends the story of my own home, more than one of the more spiritually minded told me the place had a “weird vibe” or a “strange feel”. One Sunday afternoon, my ex-wife stopped by to collect our daughter. I’d mentioned the dark history, but this was the first time she’d been inside. “It’s a nice place,” she said, “but it’s got an uncomfortable energy to it.”

I’d always been cynical about this kind of thing. But when she offered to burn sage inside the house to cleanse the negative aura, I was strangely moved. I don’t believe in ghosts but perhaps, deep down, I was superstitious. “I really think the sellers should have told you about this,” she said and frowned.

‘They had no obligation to tell you about this,” says Sam Cook, practice head of commercial and property litigation at Nockold’s Solicitors, reminding me that the starting point for any property negotiation is, and always has been, caveat emptor – Latin for “let the buyer beware”. “Ultimately, it is up to you as the buyer to satisfy yourself that the quality of the property is sound and isn’t blighted in some way,” he says.

There is legal precedent for this. In 1998, Alan and Susan Sykes bought a house in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, only to discover that, 14 years earlier, a dentist had murdered and dismembered his adopted daughter before hiding her body parts about the property. The Sykeses instantly moved out of the house, sold it at a loss of thousands and sued the former owners for failing to tell them about the house’s gruesome past. The case went to the court of appeal, where a panel of judges ruled that the vendors, James and Alison Taylor-Rose, had not been dishonest when they answered “no” to a questionnaire that asked: “Is there any information which you think the buyer may have a right to know?”

“You couldn’t get a more subjective question if you tried,” Cook says. “So the only real way to protect yourself is to do the research yourself.”

It was for precisely this reason that Roy Condrey, a US landlord and software entrepreneur, launched DiedInHouse.com, in 2013. As in the UK, US estate agents are not legally obliged to tell potential homebuyers about prior criminal activity because it is not considered a “material fact”, so he developed an algorithm to do just that. “If there’s a fire or if you’ve had building work or repairs, you have to disclose that by law,” he says. “Why not a death? Especially a violent death.”

For $11.99 a search, DiedInHouse will trawl through more than 130m police and court records, news reports, obituaries, death certificates and credit histories. For belt and braces, his team then perform a manual search to “try to fill any holes the algorithm might have missed”.

Business is booming. Condrey says he has sold more than 300,000 reports since he started – an average of around 100 a day. “No matter what people say, murder impacts a lot of people; I know it does,” he says. “If people didn’t care, they wouldn’t be buying our reports.”

It has done so well in the US that Condrey wants to expand the service into Britain. But there is one snag. “Our algorithm mainly works on digitised records, most of which only go back as far as the 80s,” he says. “To go back further, we have to research a property manually. And in the UK, history goes back for ever. You’ve got houses that are older than my country.”

Would I have used such a service, if one were available here in Britain? Unlikely. Almost two years on, I still think about what happened in my house. But part of the reason I bought it was to do it up, so that’s what I’ve been doing. As well as pulling up the bedroom floorboards and replacing them with fresh pine ones, I got in builders to add a bedroom in the loft and re-render the facade. I replaced the guttering and light fittings, painted the walls, relaid the downstairs floor with cork, built shelves and put out my books. I’ve discovered damp, and I’ve learned that the house was also used as a cannabis farm by one person who owned it after Vyas: it was the only house on the street on whose roof snow would never settle.

I am the 20th owner of this house since it was built in 1888. According to the local records office, its first owners were a warehouse packer, his wife and their two children. When Queen Victoria died, it was inhabited by a cordwainer – a shoemaker – and his family. When the first world war broke out, a wonderfully described “cutter of fancy materials” was here with his wife and three children. Another family lived here for almost 40 years from the mid-1930s, raising two sons. Now it’s me and my daughter. I haven’t told her about the house’s past because she’s too young. She’s also too busy drawing unicorns on her bedroom door.

I’ve come to realise that a house has many lives, but is only one home at a time. Harriet Evans did have a baby while living on Danbury Street, and lived there for five more years before selling up to move somewhere roomier. “In the end I came to love that house,” she says. “We became a family there, gave it so much love, and I look back on that time with massive fondness. I was sad to leave. A house’s past matters only as much as you let it matter.”

I think she’s right. My daughter and I have been happy in our house, and I think we’ll stay happy here. But although my name may be on the deeds, I no longer feel as if we really own it. We just take care of it. And for now, it’s taking care of us.