The satire boom of the early 1960s heralded the end of the age of deference in public life generally and in the media specifically. On television, Robin Day began giving politicians a tough time, and in the theatre Beyond the Fringe set a tone of mockery and irreverence that spawned Peter Cook’s Establishment club in Soho, the magazine Private Eye, and Ned Sherrin’s ground-breaking satire shows on BBC television, That Was the Week That Was, or TW3 as it became known, and Not So Much a Programme More a Way of Life.

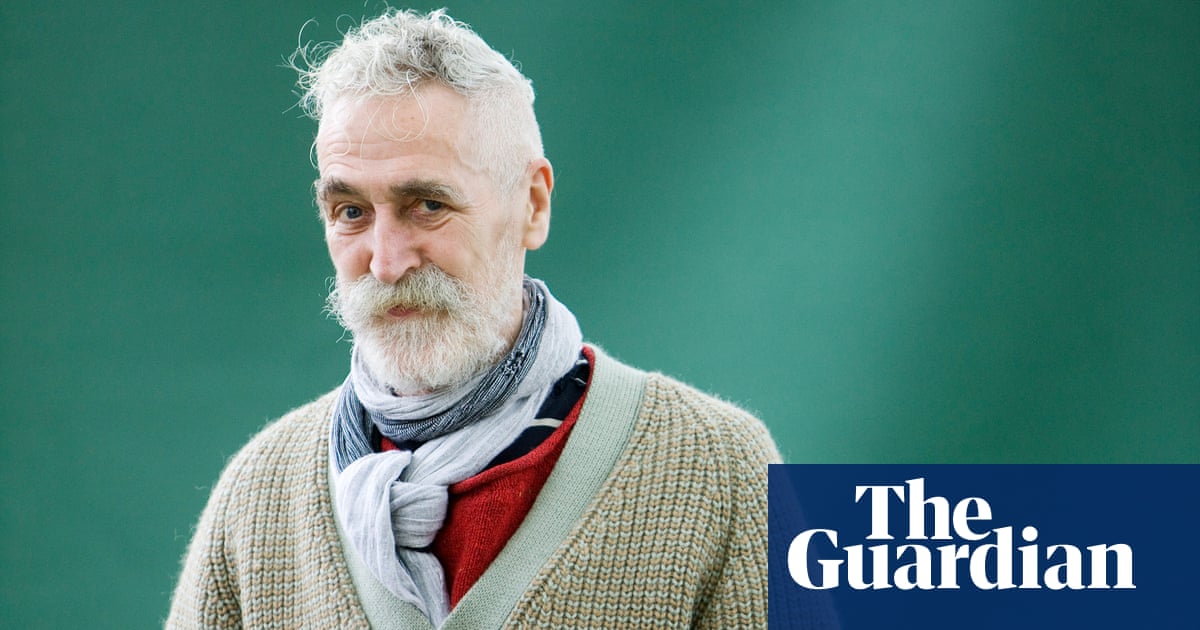

John Bird, who has died aged 86, was a central figure in this phenomenon, appearing on stage and television with a voice in various timbres of reasoning dismay, comic self-justification and utter incredulity.

Sherrin had asked Bird to be the anchor of TW3, which ran for two seasons in 1962 and 1963, but Bird declined – having coined the show’s title – and suggested he ask David Frost instead. Instead he wrote for, and appeared on, the show, alongside his Cambridge contemporary John Fortune. Once he had scored a resounding follow-up success with his sketches in Not So Much a Programme (1964-65), Bird’s path was set in popular entertainment.

His comfortably padded features, roguish twinkle and vivid turn of phrase made him an ideal and merciless impersonator of both the Labour prime minister Harold Wilson and secretary of state George Brown as well as a string of African politicians and potentates culminating in portraits of the Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta, complete with pillbox, kofia hat and fly-whisk, which drew complaints from the high commission in London, and, even more flagrantly, of Idi Amin, the Ugandan president whose “collected broadcasts” Bird released as a satirical album in 1975. The satirical lorry thundered through the narrow gap between statesmanship and thuggery, though such derisory “blackface” finger-pointing would be difficult to justify today.

Following various television and stage appearances, from 1990 Bird, along with Fortune, rebooted his career with Rory Bremner in a series of eponymous programmes over 20 years. While Bremner supplied the acidic vignettes of impersonation, Bird and Fortune perfected an improvisatory double act in which they alternated as interviewer and interviewee, the latter usually named George Parr, an all-purpose grandee from politics, big business, the armed forces and public services; Bird later resurrected one of his African despots as George MParrbe, though without make-up, whose nation was, as far as its exact whereabouts was concerned, a state secret.

Bird as Parr, otherwise, could be manifest as a Eurosceptic MP (long before Brexit), and would cut through his own screen of evasive waffle and comic xenophobia to express what he called the innate British dislike of foreigners. All foreigners? Yes. And again as Parr, now a knighted admiral of the fleet, he completely blindsided Fortune in suggesting that the large deck of an over-expensive aircraft carrier (“We can’t afford the aircraft and the carrier”) might be used to create swimming pools for the Olympic Games.

The outrageous suggestion behind all of this was that Parr, in all his guises, was somehow out of his depth, out of touch with reality and out of control in his various fields of supposed expertise. No laughing matter, perhaps, but, boy, were the two Johns funny. Between 1996 and 1999, these sketches were siphoned off into their own 15-minute slot, The Long Johns.

The final Bremner, Bird and Fortune show was a four-part special in 2008 following the economic crash. Bird was again in his element as a blithely unconcerned investment banker, quizzed by an astonished Fortune on the turbulence in the financial markets as if nothing untoward had happened at all, business as usual, and so on. The silver lining to the cloud of disaster and collapse was that he had lost only other people’s money, not his own.

John was born in Bulwell, Nottingham, the son of Horace Bird, a chemist’s shopkeeper, and his wife, Dorothy (nee Haubitz). Although he failed the 11-plus exam, he was fast-tracked by a supportive teacher into the High Pavement grammar school and thence to King’s College, Cambridge, to study English, where he soon made his mark in the Footlights.

A quiet and thoughtful man, he at first harboured serious ambitions as a theatre director at the Royal Court, home of new theatre writing, where he was an assistant, then associate, director between 1959 and 1963. He directed – after first mounting the premiere at the ADC theatre in Cambridge – NF Simpson’s surreal comedy A Resounding Tinkle (with a cast including Cook and Eleanor Bron) and George Tabori’s cabaret Brecht on Brecht, which featured the Royal Court’s artistic director George Devine and the great cabaret singer Lotte Lenya, Kurt Weill’s muse and wife, in her first London stage appearance since the 1930s.

Bird himself would never claim to have had a significant career as an actor, but he did make telling contributions to Alan Bennett’s medical farce Habeas Corpus (1973) at the Lyric as Sir Percy Shorter, a flustered doctor and president of the British Medical Association, in a fine cast led by Alec Guinness; and to Jonathan Miller’s 1970 movie version of Kingsley Amis’s Take a Girl Like You as a lecherous landlord and Labour councillor trying vainly to seduce Hayley Mills.

And two BBC series in his own name – A Series of Bird’s (1967) and With Bird Will Travel (1968) – were decidedly experimental, the first an accumulation of spoofs, sketches and satirical playlets co-written with Fortune, the second co-starring Carmen Munroe and analysing the process of presenting humour on television, with some sequences shot from a control room.

He was one of seven adult actors – the others included Helen Mirren, Janine Duvitski, Michael Elphick and Colin Welland – playing seven-year-old children in Dennis Potter’s Blue Remembered Hills (1979), an outstanding BBC Play for Today set during the summer of 1943 in the Forest of Dean. And he was ideal casting as a university vice-chancellor in Andrew Davies’s series A Very Peculiar Practice (1986), wooing Japanese investment in line with the increased commercialism of higher education in the 80s following government cuts.

Later work included a shifty and incompetent barrister, John Fuller Carp, in Clive Coleman’s Chambers (2000), and an overweening PR man, Martin McCabe, alongside Stephen Fry as his partner in crime, Charles Prentiss, in a government media relations company in Absolute Power (2003-05); both these series started out on BBC Radio 4 before moving to television.

Bird won two Bafta awards, the first as a performer in 1966, the second, shared with Fortune, in 1997, and was awarded an honorary degree at Nottingham University in 2002. He was married three times: to the actor Ann Stockdale, daughter of the US ambassador to Ireland (1965-70); to the television presenter Bridget Simpson in 1975, separating in 1978; and finally to Libby Crandon, a concert pianist.

The couple lived in Reigate, Surrey, in the 80s and had settled in Newdigate, near Dorking, in the late 90s where they raised Libby’s two sons from a previous marriage and kept two pet llamas. Never one for the bright lights, Bird admitted to having had periods of drug and alcohol dependency, at one stage claiming that his problems had caused him to become paranoid and indeed suicidal. But he was latterly a contented member of his local bowls club and patron of the Mole Valley Arts Alive festival.

Libby died in 2012; Fortune died the next year. Bird is survived by his stepsons, Dan and Josh.

John Michael Bird, actor and writer, born 22 November 1936; died 24 December 2022