Baktash Amini loved his job as an assistant professor in the physics faculty at Kabul University. As well as having a passion for teaching, he took pride in helping his students pursue careers in physics, setting up partnershipswith the International Centre for Theoretical Physics and Cern, among others.

But his efforts to further scientific education in Afghanistan seemed futile when the Taliban announced that women would be banned from university education. “The night [the] Taliban closed the doors of universities to Afghan women, I received many messages and calls from my students. I cannot find the words to describe their situation. I am an academic and the only way I could express protest was by [leaving] a system that discriminates against women,” he says. He resigned from his “dream job” on 21 December.

Prof Amini is among at least 60 Afghan academics who have resigned in protest at the Taliban’s decree banning women from higher education. “The Taliban have taken women’s education hostage to their political benefits. This is betrayal of the nation,” says Abdul Raqib Ekleel, an urban development lecturer at Kabul Polytechnic University, who also resigned from his position.

“In the last year and half, the Taliban have made many irrational demands on female students, such as regulating their clothes, hijab, separate classes, being accompanied by mahram [legal male guardian] and the students have obliged with all of them. Every professor conducted the same lectures twice every week, once for the male and then for female. Despite that, the Taliban still banned the women,” says Ekleel.

“These bans are against Islamic values and against national interest. It impacts everyone, not just the women. I could not be part of such a system,” he adds.

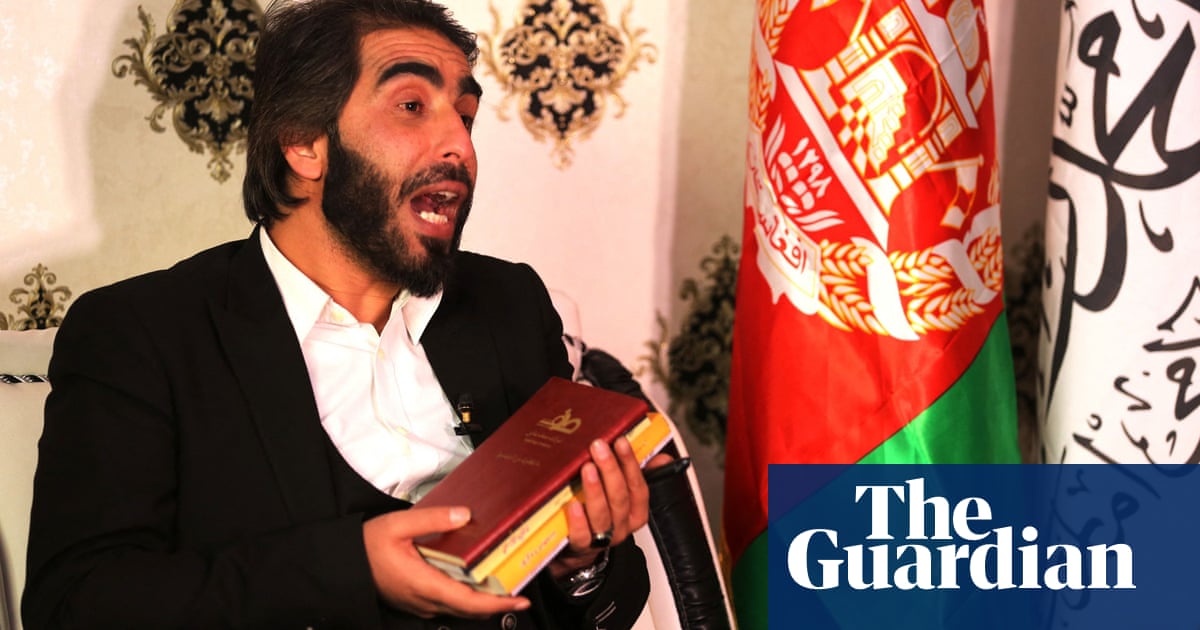

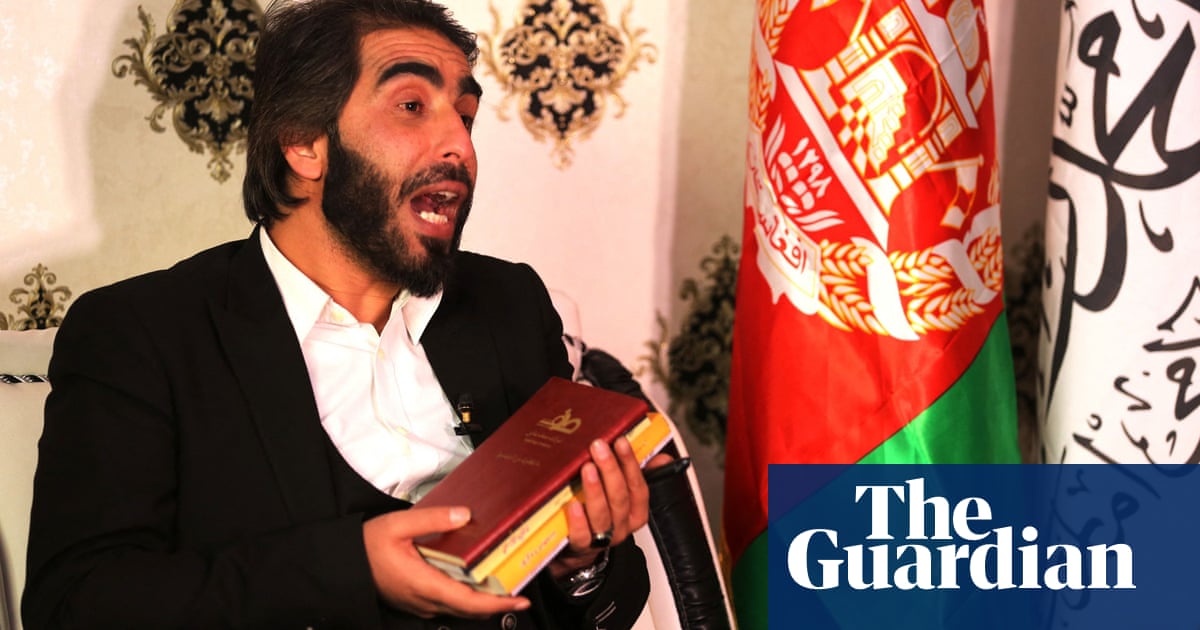

Another lecturer at Kabul University tore up his degrees and education documents on national television. “Today, if my sister and my mother cannot study, what use are these education [degrees] to me? Here you go, I am tearing my original documents. I was a lecturer and I taught [students], but this country is no longer a place for education,” said a tearful Ismail Mashal in a clip that has gone viral on social media.

When the presenter asked what he wanted, Mashal said: “Until you allow my sister and mother [back into universities], I will not teach.”

Even before the Taliban takeover, university was often a challenging environment for Afghan women, who faced harassment and discrimination. “Every day was a struggle to prove that we deserved to be there [on campus],” says 23-year-old Samira*, a final-year student. “But things have just worsened since the Taliban takeover. They kept restricting every movement, even asking questions to a male professor was forbidden. And now they have completely banned us.”

Samira had spent the evening studying for exams when she heard about the ban. “I cannot describe the pain to you. I am in my last semester. I just had a few more months to go before I graduate. I wanted to go out and scream,” she says.

That night, she wrote on a WhatsApp group with her classmates: “Doesn’t anyone care that the future of women of Afghanistan is at stake?”

Many of her female classmates were already mobilising on WhatsApp groups, discussing ways to protest against the ban. In the past year and half, Afghan women have regularly protested in the streets against the Taliban’s regressive policies, despite threats and attacks. However, few men have joined them and have often been criticised for their absence from the demonstrations in an already weakened civil society.

With the ban on women’s higher education, however, men have stepped up: as well as male teaching staff resigning, male students have walked out of classrooms and exam halls in in solidarity with female classmates.

“We stood up in support of our sisters because we couldn’t tolerate this injustice any more,” says one 19-year-old male student, who participated in the walkouts on 21 December along with dozens of other students from Nangarhar University.

Similar protests were reported in other provinces – including Kabul, Kandahar and Ghazni – with hundreds of students and lecturers staging walkouts and chanting slogans of “all or none”, demanding women be allowed backon to campuses.

“Our sisters are talented and deserve better, but also such bans on education will have a very negative, irreversible impact on our society. This is why we [Afghan men] need to speak up now,” the student from Nangarhar adds.

Dissatisfaction at increasingly regressive policies and an environment of fear created by the Taliban was already high among Afghan academics.

With the ban on women’s higher education, however, men have stepped up: as well as male teaching staff resigning, male students have walked out of classrooms and exam halls in in solidarity with female classmates.

“We stood up in support of our sisters because we couldn’t tolerate this injustice any more,” says one 19-year-old male student, who participated in the walkouts on 21 December along with dozens of other students from Nangarhar University.

Similar protests were reported in other provinces – including Kabul, Kandahar and Ghazni – with hundreds of students and lecturers staging walkouts and chanting slogans of “all or none”, demanding women be allowed backon to campuses.

“Our sisters are talented and deserve better, but also such bans on education will have a very negative, irreversible impact on our society. This is why we [Afghan men] need to speak up now,” the student from Nangarhar adds.

Dissatisfaction at increasingly regressive policies and an environment of fear created by the Taliban was already high among Afghan academics.

However, the Taliban’s brutal reaction to dissent discouraged many from taking action. One of the few academics who dared to speak out was Prof Faizullah Jalal, who was arrested in January last year.

“Previously, we wanted to demonstrate against decisions that were unjust towards our sisters. We had created groups to mobilise classmates to raise our voice, but then the Taliban found out about it and sent threats to all the group admins, and I had no option but to keep silent,” the student from Nangarhar says.

But, as the situation worsens in Afghanistan, men, particularly in academia, are now questioning their silence. “University professors cannot pick [up] a gun and stand against the Taliban and their decision. In any other democratic society, civil movements are one of the ways to fight,” says Ekleel.

“Even though there is no justice or democracy under the Taliban, the women have been protesting since the Taliban arrival, protecting our values all by themselves. I think it is our duty to stand with them.”