Roman statuary and Renaissance door-knockers, maps of the world and mortified saints; Easter parade penitents and bloodied, polychrome Christs, souls in torment and two sunbathing girls on the sand, slick with water, their bums catching the light.

In 1882, when Archer M Huntington was 11 and on his first family trip to Europe, the adopted son of American railroad baron Collis Potter Huntington found a volume on Spanish Gypsies in a Liverpool bookshop. His interest was piqued. “Spain must be much more interesting than Liverpool,” the boy wrote in his diary. Later on the trip he visited the National Gallery in London and the Louvre in Paris, and he returned home to New York with the idea of creating a museum devoted to the arts of Spain and Latin America. What a strange origin story this is.

Having learned both Spanish and Arabic, and immersing himself in Spanish history and culture on prolonged visits to Spain, and following extensive forays in Europe’s auction houses, in 1908 Huntington opened the grand Hispanic Society Museum and Library in upper Manhattan. For several years now, the museum has been closed for major refurbishments, and works from the collection have been travelling, now landing in the main galleries of the Royal Academy. Sunny Spain and black, severe Catholic Spain; the folkloric Spain of peasants and bullfighters, bodegas and Carmen; the Spain of empire and conquest, the Moorish Spain of Al-Andaluz and the before-and-after of the reconquest and the expulsion of the Jews, are all here.

Grim and gorgeous, extensive and rushed, overwhelming in its scope and oddly truncated, the exhibition has great things in it – Sevillian painter Juan de Valdés Leal’s 1661 Christ Carrying the Cross, shuffling along, back bent under the weight of the cross with its telegraph-pole timbers; Luis de Morales’ grim 1565-70 Ecce Homo and a miniature portrait by El Greco, painted on an oval bit of cardboard that one might overlook among the lustreware and glazed pottery by Muslim craftsmen, the plate depicting Jonah fishing in his little boat, the vast creature more a winged serpent than whale.

I’m gripped by a small and intimate Velázquez Portrait of a Young Girl (possibly his granddaughter), which has the feel of having been made for his own pleasure, and his Count-Duke of Olivares, former tutor to Philip IV, whose shadow throws complicated, disturbing shapes in magisterial greys on the floor beneath him. Then we are off again, among the ecclesiastical vestments and church silverware, the monstrances decorated with gold and lapis lazuli, and Giovanni Vespucci’s 1526 World Map, with its elisions and vast blanks and unknown parts. Other illustrated maps, of Tequaltiche in Mexico, with its Caxcan people engaging in gory naked battle and, in another nearby map of the Ucayali River in Peru, a major tributary of the Amazon, produced by Franciscan missionaries and indigenous artists, the local fauna is depicted, the animals frequently devouring one another.

This is also a show that attempts to tell a story as we swerve from one thing to another, and from Spain to Mexico, to Latin America and on to the Philippines. Beginning with ceramics by the Bell Beaker people, almost 5,000 years old and found unbroken by a British archaeologist in the Guadalquivir valley near Seville, and Celtiberian silver amulets and bracelets from Palencia, north of Valladolid (looking as fresh as in a shop window) and ending with a motley collection of paintings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this exhibition gives us an opportunity to see what are described as “treasures” from the Hispanic Society’s collection, all amassed by Huntington himself. He collected trunkloads of photographs, entire libraries, dozens of old masters, altarpieces and Roman antiquities, Books of Hours, illuminated manuscripts and Hebrew Bibles, Muslim textiles and ceramics, paintings by Zurbarán, El Greco, Velázquez and Goya, travellers’ maps and intricately decorated portable writing desks hefted about by Jesuit missionaries.

We travel to the further reaches of the Spanish empire, to the headwaters of the Amazon and to Bolivian silver mines, and on to the English dinner table of Queen Charlotte, consort of George III, where a gilded silver tray from Bolivia, decorated with chinchillas and other exotica, found its way in 1790. The tales of wealth and power (religious as well as secular), empires and colonialism, expulsions and subjugations and exploitation are unavoidable.

Even when it comes to Goya, in the rotunda gallery at the heart of the show, you are aware of money and power, or the lack of it. Goya’s little drawing of a woman checking her undershirt for fleas makes a great counterpoint to his full-length 1797 portrait of the Duchess of Alba, wearing the showy costume of a lower class maja, while standing beside a river on her own estate. Her finger points straight down to Goya’s signature, written as though inscribed in the sandy riverbank at her beautifully shod feet. Solo Goya (Only Goya), the painter has written, the words facing the duchess, like a message. Her shoe almost treads on his name, which she could scuff away in an instant. There is a great pictorial conceit here, in this name in the sand, in the duchess’s direct outward gaze and the contrary direction of her pointing finger. It is a painting both totally stilled and also filled with misdirection. My eyes go every-which-way with confusion, like a lover whose declarations leave them on the brink.

And then it all goes wrong, and the story becomes all about Huntington’s taste. Ignatio Zoloaga y Zabaleta’s 1903 Family of the Gypsy Bullfighter takes us back to that youthful encounter in a Liverpool bookshop. His appreciation of the Valencian-born painter Joaquín Sorolla seems to me to reflect the taste of Huntington’s monied class (Sorolla was a close friend of John Singer Sargent). He had to be persuaded to purchase works by the artists associated with Catalan modernisme, including Ramon Casas and Isidre Nonell, one of whose portraits is included here. In 1897, Nonell had shared a studio with Picasso in Paris, but Huntington never bought any works by him.

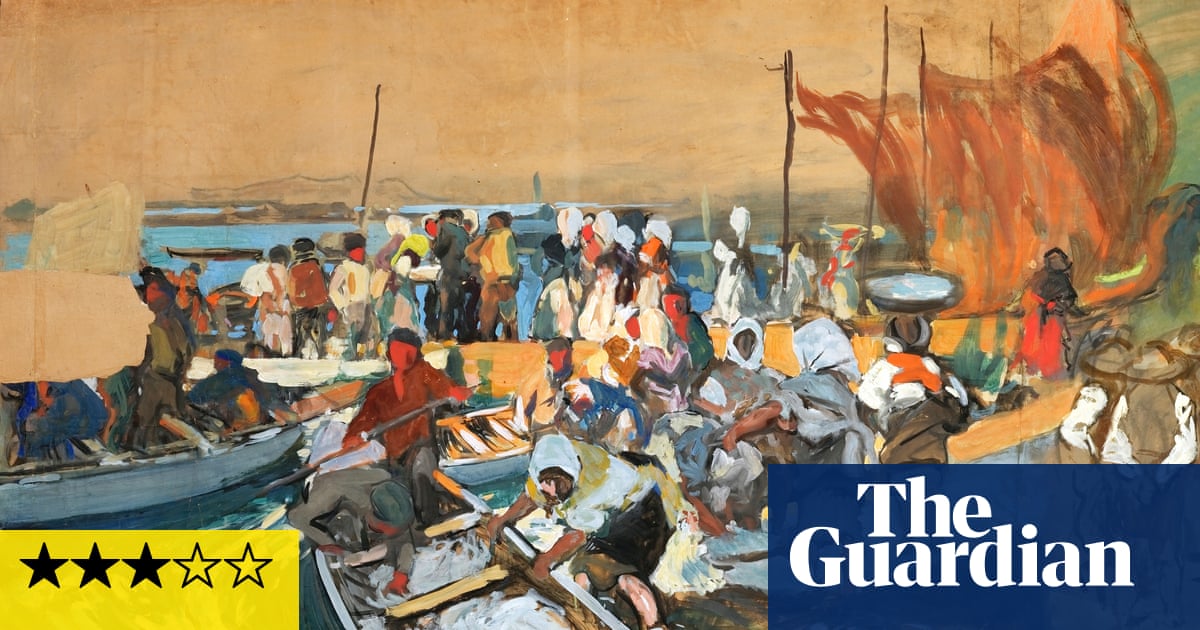

Sorolla’s early 20th-century, light-filled summery scenes – promoted as well as bought by Huntington – including those sunbathers, sleek as seals on the wet sand, give way in a final room to large gouache studies for Sorolla’s Vision of Spain, a cycle of paintings commissioned for permanent display at the Hispanic Society, depicting everyday life in the different regions. The completed works total a mind-boggling 277 feet in length. The artist toiled at these for almost a decade. They depict a backward Spain, celebrating its antic customs and fiestas, its quaint regional differences and folkloric poverty. The catalogue tells us how Sorolla employed overtly modernist techniques, such as collage, in these studies, but modernity doesn’t seem to much bother him much here. It isn’t much of an end, after all that history.

Spain and the Hispanic World is at the Royal Academy, London, from 21 January to 10 April.