One of the few good decisions that Prince Harry has made in the last five turbulent years was to take George Clooney’s advice and hire a ghostwriter as skilled as the novelist JR Moehringer. Spare is gripping in its ability to channel Harry’s unresolved emotional pain, his panicky, blinkered drive, his improbably winning rapscallion voice, and his skewed, conflicted worldview. Best of all, Moehringer knows how to drill down into scattered memories and extract the critical details that make this hyper-personal chronicle an unexpected literary success.

Who will forget the scene of monarch and grandson grasping dead pheasants, “their bodies still warm through my gloves” after a Sandringham shoot, confronting each other as she tries to escape in her Range Rover from what she knows is coming. “I’ve been told that, er, that I have to ask your permission to propose [to Meghan],” Harry mumbles. “Well then,” replies her majesty, “I suppose I have to say yes.” It’s one of the joys of this memoir that Harry is still puzzling over her answer. “Was she being sarcastic? Ironic? Was she indulging in a bit of wordplay?” One imagines that gingery face screwed up in a knot of incomprehension that no sentient reader shares about what the queen actually meant.

The most powerful character in the story, Diana, never truly appears, other than in radiant glimpses. The unassuageable anguish of the 12-year-old Harry’s loss gives Moehringer a potent, overarching literary device. His mother, Harry heartbreakingly decided, was not really dead at all. She had “disappeared”, found a way to escape her unhappy, haunted life, and make a “fresh start” (perhaps in Paris or a log cabin in the Alps). Expectation of her Second Coming freezes his heart and will not allow him to cry except once, when her coffin is lowered into the ground at Althorp. The din of the world’s mourning and the endless tawdry explorations of what really happened that night in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel, place Harry’s own memories in a lock box even he cannot access until a breakthrough in his mid-30s in a therapist’s office. The only aspect of his mother’s death that he finds unforgettable is the identity of those who caused it: the press and the paps, variously referred to as ghouls, pustules, dogs, weasels, idiots and sadists, who after “torturing” his mother “would come for me”. The “red mist” of his rage towards them never lifts. The reader is with him all the way as the hack-pack humiliates the rudderless prince for every adolescent misstep.

What Harry does not realise, however, is that his magical thinking about Diana’s “disappearance” extends to multiple other aspects of his life. He writes as if he is the first privileged male to notice the unfairness of primogeniture (the “hierarchy”, as he likes to call it with sinister emphasis). Well, duh. The monarchy invented it. The stately homes of England – belonging to many of the people he was at school with – are all inhabited by winners of the birth lottery while the younger siblings are relegated to some mouldy manor house and a sinecure at a bank (if lucky). Harry, we can all agree, has done better than most. At the age of 30, he inherited many millions from Diana and more from the queen mother when she died in 2002. (The fridge at his modest “Nott Cott” bachelor digs within the hardly shabby environs of Kensington Palace is, he tells us, often “stuffed with vacuum packed meals sent by Pa’s chef”.)

It is not so much birth order that is Harry’s problem; it’s the century he was born in, and even more so the one in which he lives. God help anyone who might have told the Red Earl Spencer, Queen Victoria’s mercurial Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, to shave off his flaming, efflorescent beard, as William told Harry. Prince Harry of Wales, his descendant, is actually a classic pistol-whirling 19th-century aristocrat always spoiling for a fight, mowing down the enemy in Afghanistan, yomping through Wales with trench foot, trekking the North Pole with a frost-bitten penis that he later cocoons in a “bespoke cock cushion” (an apt description, perhaps, of his Goop-like existence in Montecito). “You’re not terribly concerned, if I may say so, Lieutenant Wales, with dying,” his army helicopter instructor tells him. “I explained I hadn’t been afraid of death since the age of 12.”

Harry’s unreconstructed laddishness eventually starts to get as tiresome for the reader as it did for his family. What grown man of any public profile plays strip billiards with a bunch of random phone-wielding party girls picked up at a Vegas casino? Harry’s jihad against the press often ignores how much he gave them to work with. Charles’s gentle forbearance over the incident is a credit to paternal generosity and tolerance. William, who urges Harry to get help, is depicted by turns as a lugubrious stiff or a petty hysteric who thinks the Africa conservation portfolio Harry wants should be entirely his. His younger brother, one realises, as he obsessively doomscrolls through the sewers of social media and broods on slights real or imagined from his sibling, is addicted to the adrenaline of umbrage. William’s crime seems to be mostly that he grew up and Harry did not. The heir has schooled himself to accept the daunting mantle of a royal destiny, one he no more chose than Harry chose his. The latter had the army as a 10-year refuge, but does not even begin to conceive that William, equally scarred by tragedy, had no refuge at all.

Harry’s most extreme misunderstanding in Spare concerns the topic he affects to know most about: how the deep state of the Palace works. Harry prefers to blame sycophantic double-dealing courtiers when the decisions handed down are those he doesn’t like. By his account, the queen’s private secretary Edward Young blocked the meeting at Sandringham that Harry requested in January 2020 to discuss the Sussexes’ plan to become part-time royals. The possibility that the monarch herself was having second thoughts about the wisdom of such a meeting (Granny’s diary was suddenly full) isn’t entertained.

The debacle of Megxit plunges Harry into a crisis that elicits the most clear-sighted assessment of his own predicament in the entire book. Holed up with Meghan and Archie in a fortified Los Angeles crib courtesy of writer-director Tyler Perry, he reflects that “after decades of being rigorously and systematically infantilised, I was now abruptly abandoned and mocked for being immature”. There are more ironies. While the recurring plaint of Spare is the power that his father and brother hold over his life, the truth is how circumscribed their power actually is. Charles tells his “darling boy” to put all his proposals for a hybrid royal role in writing not because he’s stalling but because, as he says: “It’s all decided by the government.” The worst blow Harry lands on his family is that, just four months before his father’s coronation, he has made them all look so small. When you let daylight in on the Palace, it turns out to be a threadbare movie studio where contract players tot up their self-reported public appearances in the court circular and vie for the biggest roles and the most favourable reviews. In Harry’s telling, most of the family rows are about competition for the best coverage. One example given is that Kate is warned not to pick up a tennis racquet during a visit to a sports centre in case the fetching image takes Charles off the front page. There is an unceasing flow of leaks, background plants and targeted gossip by aides, designed to make one of the principals look good at another’s expense.

As we all know, Harry’s gravamen, the nub of his incandescent fury, is how he and Meghan were sold out by the institution. But one senses that his rage has another source: deep marital embarrassment. Harry’s most profound act of magical thinking was the promise of what he could deliver his bride. In the ecstasies of infatuation – and of relief that he’d finally found someone “perfect, perfect perfect” – he boosted his beloved’s fantasy of their life together as world-dominating humanitarian superstars powered by her Hollywood glamour and his royal stature. Sitting on the Ikea sofa of Nott Cott, how could he tell her that, in the grand scheme of the monarchy, he was a penny-ante prince? His great big dreams revealed how small he was: one can’t help but feel that it’s this that he really wants an apology for.

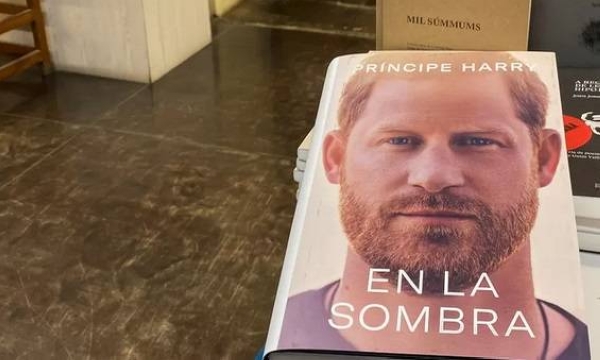

Spare by Prince Harry the Duke of Sussex is published by Bantam (£28). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.