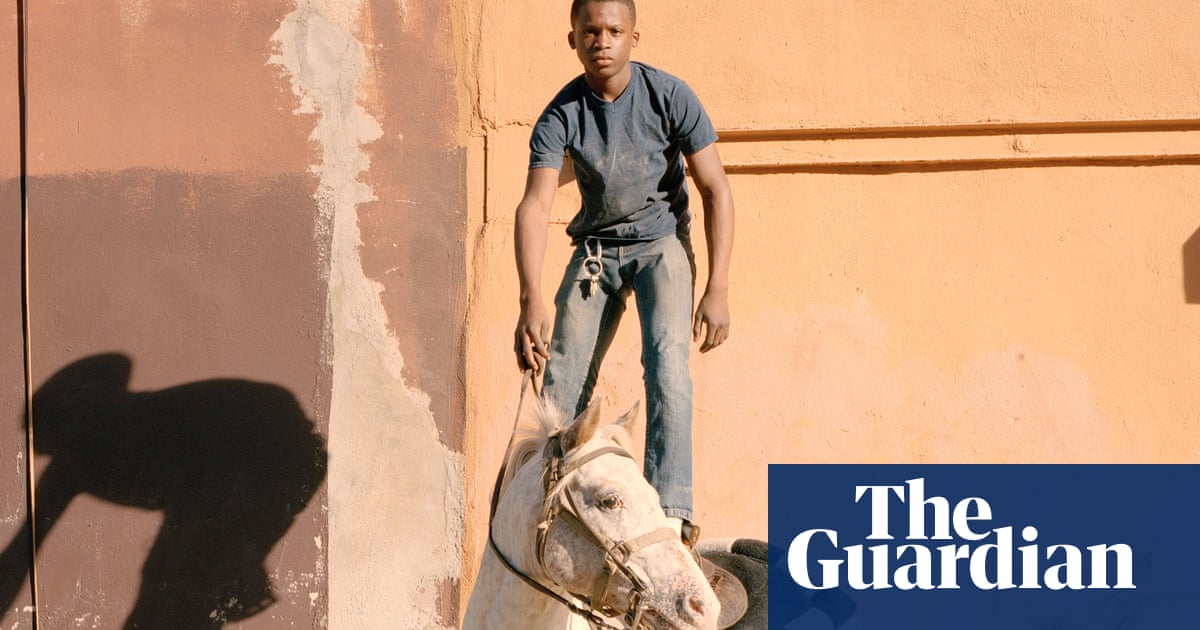

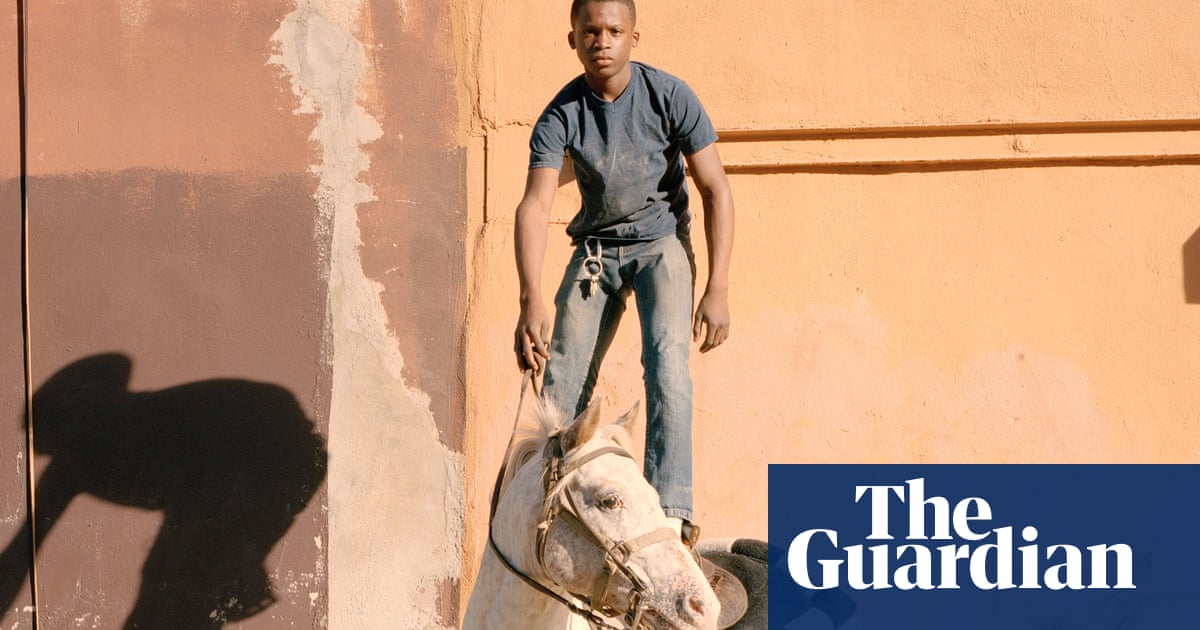

Icame across Philadelphia’s Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club online. Black horsemen hadn’t really seeped into the public consciousness at that time, but as soon as I found a picture of a black man standing on a horse, I started researching further so as to figure out the context. It was 2014 and I was a broke graduate, so I couldn’t afford to do a project about it. But after a commission for London’s Now Gallery, I finally was able to fly out to the US in 2016.

It was my first time in the country and, halfway through my two weeks there, Trump was elected. Part of me really likes the US and part of me dislikes it. I don’t think the UK is particularly great in terms of how our government treats the people, but the US is on another level. There is a sense of abandonment. People are left to fall through the cracks at a much faster rate.

While my initial interest in the stable came from the fact that it was so visually striking, it was the historical context that drew me in deeper. I found out that in the first Kentucky Derby, in 1875, 13 of the 15 jockeys, including the winner, were Black. There was a long lineage of Black horse riders, which made sense when the people looking after the horses were enslaved. But there have been Black people riding horses in the city in Philly for more than 100 years, and a lot of stables have popped up in abandoned buildings since manufacturing collapsed in the US in the 80s.

There’s another stable in Brooklyn, and a big one in LA – the Compton Cowboys. Guinness did an advert with them a year or two after I made this project. There are loads in the south as well, generations of people who kept horses.

I called my project Concrete Horsemen. It became centred on African American identity, and the public perception of what it means to be Black, and I wanted it to bring to the forefront the contributions that African Americans have made to horse culture in the US. I used the word horseman because cowboy has racist connotations dating back to slavery. Enslavers would refer to the person who handled the cows or horses as the “cow boy” or the “horse boy”, whereas white cowboys were called “cowhands”. Today when you think of cowboys, the iconography is people like Clint Eastwood.

Part of the purpose of Fletcher Street is that it’s a way of teaching kids discipline and keeping them off the streets. The area is 97% African American, over half of the people live below the poverty line and there is a high rate of gun crime. But I was trying to show a positive side because what these people are doing is amazing. Younger kids clean the stables out and get to ride the horses as a reward. It’s a community project as well as being a clubhouse. The first few days I barely made any pictures, I just spent time hanging out and playing basketball with members like Kareem, who is pictured here. There are some women involved but it’s mostly male at the moment. A lot of the younger guys were starting to have kids and a lot of those are girls, so I’m guessing the next generation of riders will be more female.

I don’t like the label “photojournalist”, which I associate with people parachuting into other countries and creating “poverty porn” and presenting it as objective truth. The idea that the camera doesn’t lie stems from early photography, when it was the most realistic way of documenting things, but I don’t think photography can be unbiased. It is always heavily influenced by the photographer, consciously or not. So rather than a photojournalist, I would describe myself as someone doing documentary portraiture which is heavily influenced by research. There has to be some substance behind it. It’s not hard to make a nice picture: the challenge is to make work that’s beautiful but also has depth and some sort of message. Or to document something interesting that isn’t well known.

I feel that Concrete Horsemen had an impact. Since I did the project, there’s been a Netflix movie with Idris Elba, set in Philly, called Concrete Cowboys. One of the guys I photographed at Fletcher Street is one of the main characters in the film, which makes me happy. There’s also a scene in the 2022 horror film Nope, in which Daniel Kaluuya rides a horse in jeans and an orange hoodie that is exactly the same shade that a rider has in my Concrete Horsemen series. It’s interesting how little things seem to trickle into other stuff and affect the wider artistic discourse.

Cian Oba-Smith’s CV

Born: London, 1992.

Trained: Photography at the University of the West of England.

Influences: Gordon Parks, Malick Sidibé, Alec Soth, Paul Graham, Deana Lawson

High point: “Seeing my work hanging in the National Portrait Gallery for the Taylor Wessing in 2017. My teacher Ms Miller took us there during our A-levels and I never dreamed I’d have work there.”

Low point: “My cousin taking his own life in 2017. I felt indifferent to photography and life in general, the loss sucked the colour out of everything and it was a long time before I could see the joy in things.”

Top tip: “Make work that you’re passionate about and you feel needs to be seen. If it resonates with you it will resonate with others.”