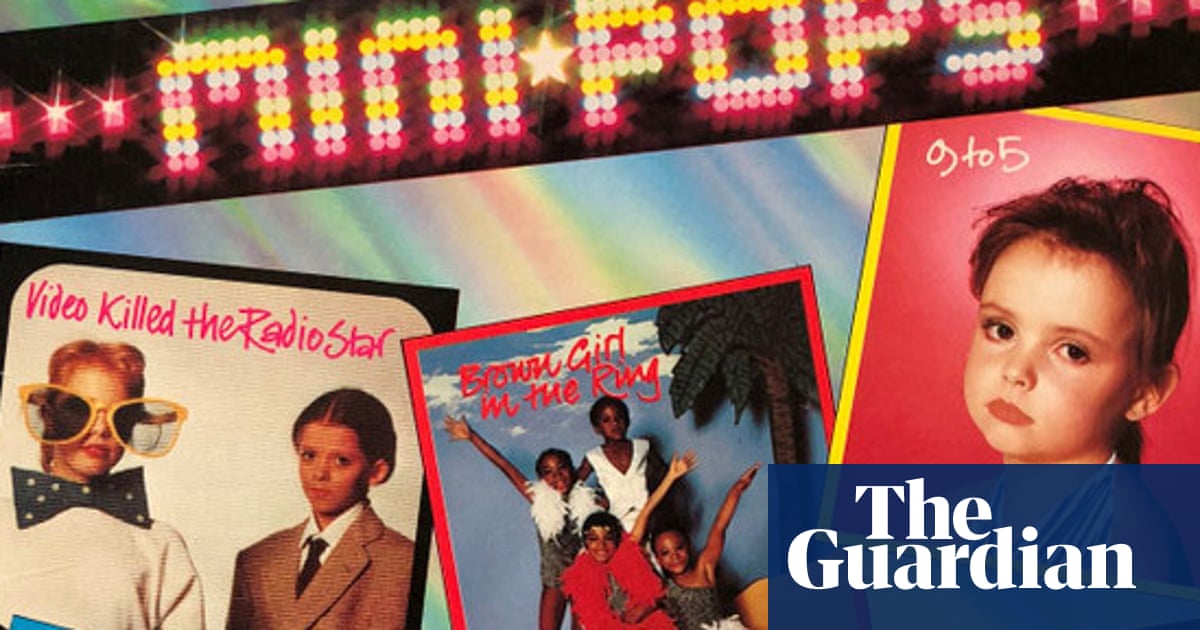

Forty years ago today, at 6pm on a Tuesday evening, Channel 4 screened the first episode of a new children’s television show called Minipops. It promised to showcase talented preteens singing pop covers, which sounds anodyne and inoffensive. It proved to be anything but.

The girls, plastered in makeup and as young as seven or eight, wore costumes ranging from chiffon nightwear to short skirts and high boots. The boys wore denim and leather, often with bare chests. Iffy song choices resulted in sights such as a small child singing: “Night time is the right time, we make love.”

The media backlash was savage. The Observer asked: “Is it merely priggish to feel queasy at the sight of primary school minxes with rouged cheeks, eye makeup and full-gloss lipstick belting out songs like torch singers and waggling those places where they will eventually have places?”

The Sunday Times referred to the performers “lasciviously courting the camera. This is aggravated by lashings of makeup on mini-mouths and rippling leather wrappings around embryo biceps ... In the twinkling of an eye the childhood of these children seems to have been stolen from them.”

Minipops has become a byword for televisual disgrace, legendary in its awfulness. In 2006, 23 years after the programme was broadcast, the Radio Times placed it second in a countdown of the 50 worst programmes ever made. In 2005, Channel 4 showed Whatever Happened to the Minipops?, a documentary in which the Guardian’s erstwhile TV critic, Grace Dent, summed up the lingering sense of shame: “If you were part of the Why Don’t You gang, it’s the kind of thing you can trot out at a party and it’ll probably get you laid. If you’re one of the Minipops, you’ve got to keep it to yourself because people will think you were part of a paedophile ring.”

Joanna Fisher was the youngest Minipop, the longest-serving member and the star of its most controversial moment. Her rendition of the Sheena Easton hit 9 to 5 (Morning Train) saw her deliver the fateful line about “the right time to make love”, dressed in nightwear. She, more than anyone, must look back at Minipops with a jaded eye.

Or not, as it turns out.

“It was such an incredible experience,” she says. “We met practically every single star that we covered, we sang with them, we did interviews with them. I’ve got photographs of all the superstars of the time, and the Minipops standing next to them.”

Fisher was spotted, aged five, by Minipops producer Martin Wyatt in 1980. “I was dancing in a children’s discotheque in Maidenhead called Skindles – and Martin Wyatt came up to me and said: “Are your mum and dad here? Would you like to be in a pop group?”

Fisher and four others (including Wyatt’s daughter Joanna) became the founder members of the MiniPops. They recorded their first album at Abbey Road in 1981, and received a gold disc, marking 100,000 sales, on ITV’s Saturday morning children’s show Tiswas. They enjoyed healthy album sales across Europe, and a number one single in France. Then, after numerous TV appearances, they were given their own show – with other children recruited to star alongside the band.

Speaking years later, Wyatt attempted to partly explain the children’s image by claiming that producers had discovered, after the event, that the girls on the show kept going back to the makeup artist and claiming they had been told to have more applied. Although he did take responsibility for the results: “I can’t blame anybody other than ourselves … We should have seen them on set and said ‘too much’.”

It wasn’t solely Wyatt’s responsibility. Channel 4 commissioners signed off on the show. As the director of programmes, Liz Forgan, said afterwards: “Sometimes you can spot that the basic idea is rotten. Sometimes you can spot that the research isn’t going right. Sometimes you can spot it at rough cut. And sometimes you don’t spot it till it’s too late to do something about it.”

Fisher says she wasn’t concerned about how the show was received. “I was seven or eight. Do you think I cared?” But she has her suspicions that Channel 4 was delighted at the notoriety of a show that brought in an impressive two million viewers. “The negative press was purely, in my estimation, designed to put more people’s eyes on it … There is no such thing as bad publicity. The more they were shocked, the more they tuned in. If you’d just said, ‘Oh my God, it’s fabulous!’ people probably wouldn’t watch it.”

Minipops was, not surprisingly, cancelled after one series. But the band continued, releasing six more albums and enjoying particular success in Canada, where they went on a three-week tour. Fisher recalls performing to audiences of 20,000 and touring the streets on a float. “It was the most unbelievable experience any kid could possibly have had.”

After eight years, she left the band, going on to achieve sporting success in tennis (ranked British No 1 for her age) and equestrianism, where she was twice shortlisted for the Olympic team. She has lived a varied and interesting life, and looks back on Minipops with unadulterated fondness. But there is lingering regret at how the show has come to be regarded. “We had a reunion get-together in 2005 [for the documentary]. It doesn’t matter how nicely you portray the time, and how much fun you say you had, and how wonderful the experience was, they always show it as negative. It is the most bizarre thing. I don’t understand it.”

Surely, as an adult, she can see that some of the material, and the way it was shown, was inappropriate? “We were only having fun – getting dressed up and putting on makeup, and dancing around the stage? Kids do it every single day. It’s totally normal.”

But not all kids end up on TV, performing adult lyrics. “What were they meant to do? Change the lyrics? 9 to 5 is actually a really upbeat song about how she can’t wait to see her man. I don’t see anything wrong with it. If adults saw it in the wrong context, wouldn’t you ask the adult why they were watching it? Minipops was designed for children, and it was performed by children. It wasn’t designed for people with perverted minds to sit there and get excited.”

Like Fisher, most of the Minipops stars have gone on to enjoy successful and fulfilled lives. The tragic exception is Scott Sherrin. After appearing on Minipops, he starred in West End musicals, appeared in the Royal Variety Performance and, in 1991, became a regular presenter on That’s Life. He went missing in 1995, amid signs of erratic behaviour, which his sister later attributed to repeated use of cannabis. His body was found in the River Thames in March 1996.

The rest of the Minipops cast, Fisher warns, will not want to talk. She is correct. Emails go unanswered. One of the group’s female members replies politely, saying she loved being in Minipops but has put it to bed. Given the show’s notoriety, their reticence is understandable. Fisher, too, is wary of being misrepresented. “I do hope you write exactly what I’ve said. I said it from the heart.”

It is easy to be snide about Minipops. I’ve done it myself. But the idea was a good one. The problem wasn’t the concept, but the execution. Cecil Korer, the head of light entertainment at Channel 4 who commissioned the show, remarked sadly: “Its reputation has sullied its innocence. It’s just kids pretending to be pop stars.”

And that is all it should have been. The real shame about Minipops was that it could have been a sweet bit of sugary escapism for youngsters and run for a few years, before fading into fondly remembered obscurity. If they had chosen the songs more carefully, toned down the outfits, and spared the makeup, it would have been an innocently charming series showcasing gifted performers.

The Minipops really were gifted. Which is how Fisher chooses to remember the show. “I think the children were incredibly talented and incredibly beautiful. And I look back at every one and think: didn’t they do a great job?”