Even if policymakers have the right objectives, their intentions are often frustrated by limited policy levers or fall flat on contact with the real world.

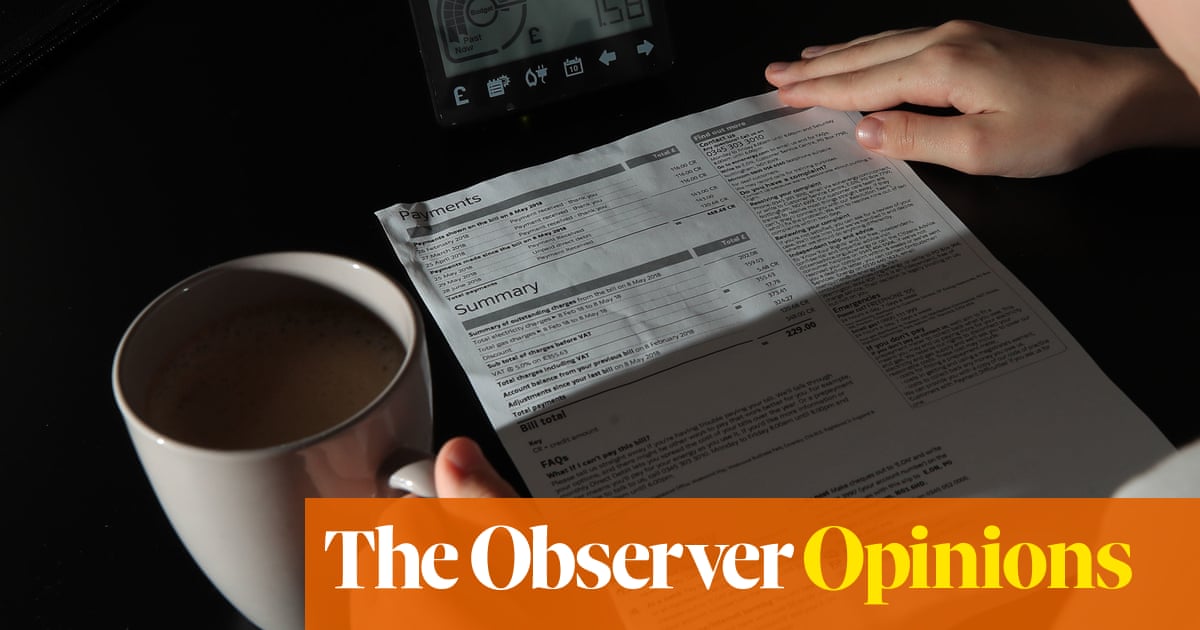

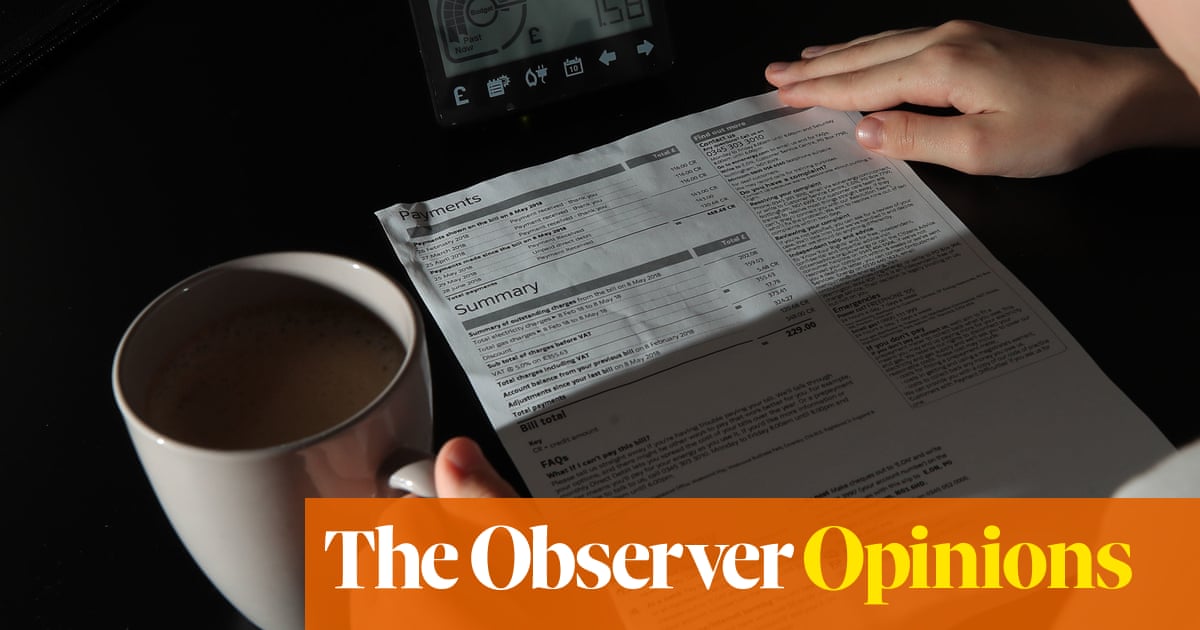

Take energy bill support. The inability to immediately target bill reductions at poorer households is why government is capping all our energy costs at the equivalent of £2,500 for a typical bill. The Treasury’s understandable discomfort with that means the cap is rising to £3,000 in April before ending a year later, with the government consulting on a longer-term “new approach to consumer protection in energy markets”.

This will need to be a social tariff, reducing bills for those on lower incomes. But how that is designed needs to reflect lessons from similar markets, with any social tariff applied automatically.

Early in the last decade, water meters were installed across the south-east, raising bills for many. To compensate, families losing out could apply for a bill reduction for the first two years. Requiring people to apply for the discount was meant to target help at poorer households. What actually happened? Well, 70% of those eligible missed out, losing £120 on average, and households in richer areas benefited most because of greater attention to utility bills among the rich.

This is also why richer households profited from competition among energy suppliers before the current crisis, while poorer households doing less switching got stuffed. Being poor doesn’t just mean fewer pounds in your pocket – it means more stress and less time to pay attention to energy bills. New US research shows it means having to wait longer for everything from grocery shopping to medical appointments. Policymakers need to understand that income taxes might be progressive – but time taxes certainly aren’t.

Torsten Bell is chief executive of the Resolution Foundation. Read more at resolutionfoundation.org