RIYADH: It is often believed that education is the most powerful tool humanity holds; it can determine a country’s strengths, quality of life, and even change the world as we know it. That message was not lost on the great Imam Mohammed bin Saud, the founder of the First Saudi State in the early 18th century.

As the imam’s vision was based on change and evolution, key areas were the revival of education and culture. From shambles, he united a region by developing innovative learning methods, providing safety for grassroots initiatives to thrive, and making Diriyah the building ground for education in the renaissance era.

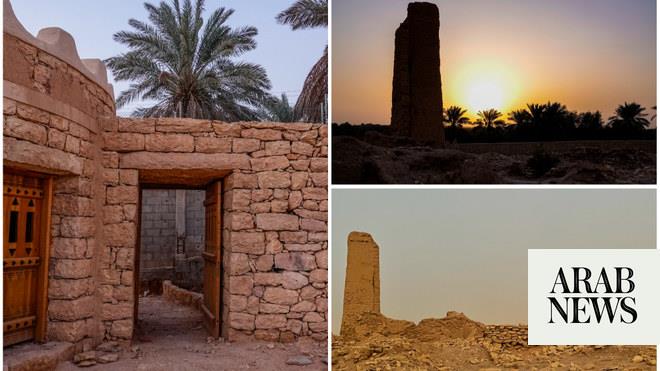

The historical Diriyah, the landing ground of the First Saudi State, was already growing in its own right upon its establishment in the hands of Prince Mani Al-Muraydi, the predecessor to the Saud family, in 1446.

Faisal Alamer, a Saudi historian and researcher, told Arab News: “Diriyah’s scientific and educational aspect was at an adequate level for Diriyah’s residents during that period.

“However, when Imam Mohammed bin Saud established the the First Saudi State in 1727, this large development started emerging in different fields, fundamentally due to unity: the state’s unity, the establishment and annexation of Arabia as one state, and the enforcement of security and stability in the region.”

At the forefront of those developments was education as an essential pillar in the establishment of the First Saudi State. He took to building hundreds of schools and mosques, the main learning institutions at the time, concentrating on the Al-Bujairi area as a hub for academic enlightenment in Diriyah.

The leader made a point to provide any means for education — such as accommodation and meals — which attracted many scholars and knowledge seekers to the area.

Alamer said: “The aim was to invest in people and the youth, and to develop the existing human cadres at the time.

“Levels of education included the first level up to the level of books where they (the youths) were taught to read and write, as well as memorize the Qur’an and learn the principles of calculus.”

Imam Mohammed bin Saud took to building hundreds of schools and mosques, the main learning institutions at the time. (DGDA)

The beginning stages of education took place in “kataatiib,” dedicated spaces where individuals could learn reading, writing, Qur’anic studies, Islamic sciences, math, and the fundamentals of the Arabic language.

The sessions were led by teachers, and children were sent to kataatiib as early as they were able to gain awareness of the real world.

The imams themselves would contribute to the teaching, presenting lectures and classes, while their own councils were never short of discussions.

Students would then move on to higher schooling stages, delving deeply into details of scientific and arts topics, usually within the mosque, much like todays higher education.

Penmanship amongst students was one of the key focuses, as calligraphers were a great asset to the book-printing craft. Students would write on their individual studying boards, and those with unique and proper techniques would receive the opportunity to present their work to Imam Ibn Saud.

“The imam rewarded good handwriting, he supervised this work himself, thus underscoring the keenness that this country and its leaders accorded to the educational and cultural fields,” Alamer said.

An aspect that is greatly de-emphasized in our modern recollection of history is the great democratization of the education system and its support toward women.

“(The state) was keen to educate women and teach them how to write in that period, and did not limit [education] to a certain class. Similar to male educators who taught boys, women had female educators who educated them, helping them become poets and authors,” Alamer added.

As the education system continued to develop, so did the artistry and tools. With the growing interest in writing and reading, the profession of wiraqah came to surface.

Warraqs were professional scribes dedicated to making written copies of books, the precursors to today’s printers, who made up a significant portion of the population in Diriyah.

It was a noble, but accessible, job, nonexclusive to a certain group or division, and many of them gained fame or popularity for their unique penmanship, including Ahmad Al Marshadi, Abdullah ibn Ghanim, Abdul Rahman ibn Issa, and others.

Naskh and Al-Reqa was the special font in Diriyah at that time, the most common scripts in the Najd region, written by pens made of reeds. Scribes would match the durability of reed pens with the corresponding paper, which they received blank, and hand-lined using thread.

Penmanship amongst students was one of the key focuses of schooling, as calligraphers were a great asset to the book-printing craft. (DGDA)

Inkwells were produced within the Najd region using wood, most popularly tamarisk, and were greatly valuable to writers. Various types of ink were manufactured such as al midad.

Alamer said: “Attention was no longer limited to the mere acquisition of a book or just calligraphy, it extended to the manuscript itself.

“The aesthetics of the manuscripts began to appear, in addition to the writing colors. They relied heavily on black, but there were also other colors such as green, red, and yellow.

“Various geometric shapes, namely triangles, circles and cross lines, were used to decorate and beautify these manuscripts. The top of the manuscript was decorated with flowers, making it more attractive.”

The location also played an important role, given its position in the middle of Arabia, trade and Hajj routes. This strengthened education in the area, leading scientists to visit it, meet people, and exchange knowledge.

The imam’s reign was an essential pillar in elevating the quality of life and spreading knowledge across the First Saudi State. Through unity, it quenched the thirst for education in a renaissance period that solidified Diriyah as a beacon of educational wealth, continuing the historical legacy of Arabs as leading scholars.