Experts from the auction house discuss some of the highlights from the Al-Zayani collection of modern and contemporary art from the region

DUBAI: On April 25, Sotheby’s will be auctioning a collection of more than 80 modern and contemporary works by Arab artists. All are owned by Bahraini collector Abdulrahman Al-Zayani, “one of the leading collectors in the Middle East,” who, along with his family, has amassed “a multitude of artworks from the historic Islamic world to modern and contemporary international art and design.”

“Exploring myriad themes and mediums, each work represents a different aesthetic whilst tying into a rich thread of cultural heritage,” a press release states.

“It’s an important collection for a few reasons,” Sotheby’s contemporary art specialist Ashkan Baghestani tells Arab News. “First, single-owner sales of modern and contemporary Arab art are quite rare in our region. Secondly, this collector has bridged two worlds, bringing them together with his vision, his taste and his passion. It will speak to the older, more academic collector, but also to a younger one.”

For sales purposes, Baghestani explains, Sotheby’s categorizes “modern” art as being “from the first modern movements in Egypt in the 1920s,” while “contemporary” means “everything from the Eighties to today” — though he stresses that there are some “nuances” and some artists that fall into both camps.

Here, Baghestani and Alexandra Roy, Sotheby’s head of sale for 20th Century Art / Middle East, discuss some of the highlights from the collection, many of which will be exhibited in Dubai from Feb. 28 to March 3.

Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar

‘Untitled’ (Gratzella"s Portrait)

Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar, ‘Untitled’ (Gratzella"s Portrait). (Supplied)

The acclaimed Egyptian artist is known for his “surrealist, out-there work,” Roy explains. “But during a short period of a couple of years when he studied in Rome, he shifted his style dramatically and focused on portraits. But there’s only a handful of them.”

That makes this portrait from around 1960 of a young girl called Gratzella, extremely special — one of the works in the collection that, Baghestani says, should attract interest from institutions “because these are early, really important, works that you can’t simply buy on the market.”

“I think there’s something very sweet and very moving about this portrait,” says Roy. “It reminds me a bit of Modigliani.”

When El-Gazzar returned to Egypt, he immersed himself in Sufism, focusing on “religion, people on the fringes of society who believe in these mystical experiences,” Roy explains. “This portrait (was created during) just a short break from that; it’s so unusual for him.”

Fouad Kamel

‘Untitled’ (The Drinker)

Fouad Kamel, ‘Untitled (The Drinker).’ (Supplied)

Kamel is a seminal figure in the development of modern Arab art, as a founding member of the surrealist Art and Liberty Group — a collection of poets, artists, and writers, many of whom had studied and worked in Europe. When the Second World War began, they returned to Egypt inspired spiritually by the fight against fascism and aesthetically by cubism and surrealism.

“Before, there was this very academic, (classical) European, way of looking at art,” Roy says. “They were breaking away from that. They were very focused on nationalistic issues that were happening, as well as post-war inequality.”

This piece, from 1941, “embodies this entire movement,” Roy explains. “This disfigured body of ‘The Drinker’ is symbolic of the anxiety that was caused by the Second World War, but also by all of the social pressures in Egypt at the time. They’re fighting against the status quo and using surrealism to create these extraordinary, powerful artworks which have a very strong political influence.”

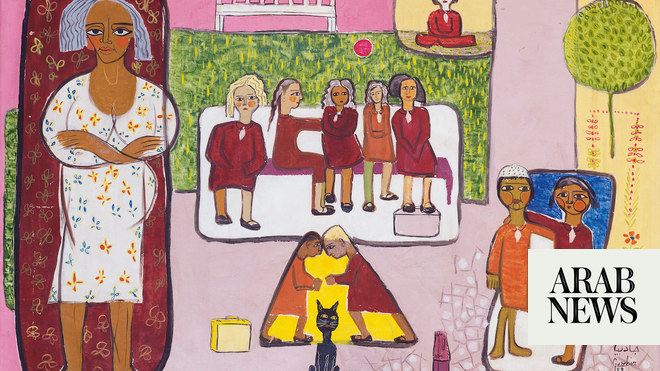

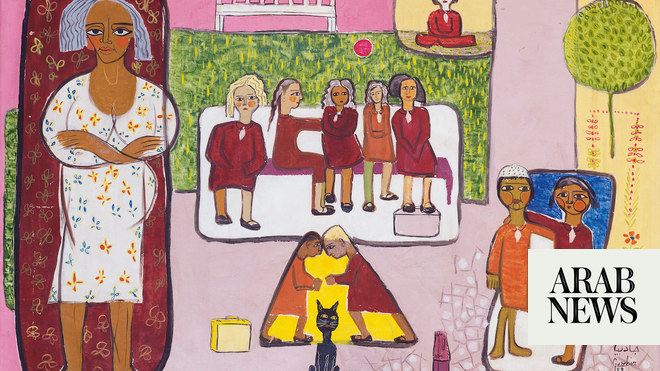

Gazbia Sirry

‘The Garden’

Gazbia Sirry, ‘The Garden,’ 1959. (Supplied)

Sirry is, Roy says, “considered one of the best artists of her generation” and this work from 1959 brings together a number of her favorite themes. While there are political aspects to her work — as with many Egyptian artists at the time — Sirry also focused on people’s inner lives. “It’s a very introspective painting,” says Roy. “She’s using a landscape of memories; that’s the best way to read this work.”

The woman on the left of the painting, Roy points out, “looks a bit like a mummy,” evoking the country’s pharaonic works. “A lot of these artists were looking back at pharaonic times, but many were also educated in Europe, so there’s this interesting mixture as they try to forge their own cultural identity. Once you start to read these paintings in that light, you understand they’re so different from anything else: You have these fragments or evocations of what they’ve learned, but also the history and political conditions of their countries. Modernism in Egypt was happening at the same time as a lot of changes, politically. And each artist responds to them differently.

“There’s something very happy about this painting, with the bright pink. And there’s something very unusual in the layout also,” she continues. “It’s not the usual way to present a narrative in Western paintings; you have different scenes happening at different times. And you see that in Islamic miniature painting — different elements of a story placed on a page. This is a bit of a coming-of-age for her; it’s a woman looking internally at her own relationships.”

Hassan Hajjaj

‘Miriam Green’

Hassan Hajjaj, ‘Miriam Green.’ (Supplied)

The Moroccan artist’s vibrant singular style has made him one of the most collectable artists around. This piece demonstrates a different side to Al-Zayani’s taste.

“We’ve been talking about these modern artworks that are imbued with a lot of nationalistic symbolism and history, and then you have someone like Hajjaj, who’s also making a commentary about Orientalism, about the way that people are portrayed — making a statement on media, consumer culture, vanity, all of that. But doing it in a funky, quite playful way,” says Roy.

“What I really like about this collection is that includes some very serious pieces, but also these more fun, playful works that lighten the mood. When you walk into Al-Zayani’s home, though, you see a synergy between them.”

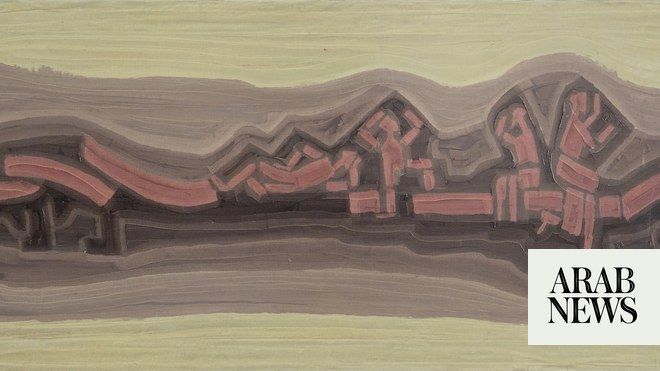

Farid Belkahia

‘Untitled’ (1981)

Farid Belkahia, Untitled, henna on vellum laid on panel, 1981. (Supplied)

“Belkahia is by far my favorite Moroccan artist,” says Baghestani. “He’s the one who really revived this idea of craftsmanship in art, which was overlooked after most of these artists came back from Europe having embraced more contemporary practices.”

“He studied in Europe in very rigorous academic conditions, moved back, and then was looking to reinvent how to teach art in a local setting,” says Roy. “So, his focus was very much on craftsmanship — classes that included carpentry, jewelry, and carpet making.”

Each of the characters on this vellum-based work are inspired by Berber iconography, Roy explains, “And he’s looking at phenomena of trance as well. Like El-Gazzar, who was fascinated by Sufism and mysticism, Belkahia’s looking at the way that people use these half-conscious states. This painting evokes that.”

Fahrelnissa Zeid

‘Erbil: Réalités Nouvelles’

Fahrelnissa Zeid, ‘Erbil: Réalités Nouvelles.’ (Supplied)

Zeid, says Baghestani, had “a fascinating life.” She married into the Hashemite royal family, but was also “one of the most radical female artists from the region.”

Zeid was educated in the West and her work was shown in major European exhibitions from the 1940s onwards. “She fully embraced abstraction at an early age,” Baghestani says. “Her mosaic works, like this one — an extremely rare piece from the early Fifties — look like ancient Byzantine mosaics, but also embrace futurism and abstraction. She had such a three-dimensional mind. When you stand in front of these paintings, they’re incredible. There’s such a depth to them. You’re transported. They’re almost mystical.

“At a time when figuration was prominent, a few artists — and Zeid was one of them — really embraced abstraction,” he continues. “That really wasn’t the trend at the time, but now they’re finally getting the respect and treatment they deserve.”