The story of art and its protagonists in the first half of the 20th century is a pretty familiar one. But the procession of star names inventing art’s various “isms” inevitably leaves out artists who chose to operate away from the cutting edge, yet who in their day were well known, celebrated and well rewarded for their work.

One such artist is James McBey, (1883-1959) who has found a new champion in the journalist and writer Alasdair Soussi. Soussi not only published a biography of McBey last year, but is now curating an exhibition dedicated to him at the Aberdeen Art Gallery.

“There are lots of possible reasons why McBey is not so well known these days,” says Soussi. “He was not particularly clubbable and never really joined the arts establishment. He was also most esteemed for the now unfashionable art of etching. But aside from being a stellar artist, he had the most extraordinarily adventurous, almost cinematic, life and I think the time is right to reassess both.”

McBey’s biography is indeed a full one. Born out of wedlock in rural Aberdeenshire in 1883, he had a fraught relationship with his mother who later took her own life. He left school at 14 to become a bank clerk, but by his mid 20s was a largely self-taught and successful artist and etcher. By 1917 he was the official war artist to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force; his portrait of TE Lawrence is part of the Imperial War Museum’s collection.

On his return from the war, McBey was routinely described as an heir to Rembrandt and Whistler as an etcher and print-maker. His success coincided with a boom in the prices of some of his prints, which fetched up to £30,000 each in today’s money.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash put an end to the speculative price bubble but by then McBey had a grand London townhouse. He spent the second world war in the United States engaged in unsatisfying but lucrative work painting portraits of business leaders and justices of the supreme court, and in 1946 he returned to north Africa, where he lived out the rest of his life as a leading figure among the louchely artistic Moroccan expat scene.

While McBey’s work is held in collections all over the world, Aberdeen is his spiritual home, and the gallery there boasts a comprehensive permanent collection of his work. Soussi’s new exhibition acts as a biographical guide to the man behind the art, displaying artwork as well as family photographs and diaries.

“He kept everything and he recorded everything,” says Soussi. “His diaries are an absolute treasure trove, not least about his very complicated love life.” McBey had innumerable affairs before and after his marriage to his wife, Marguerite, details of which he recorded in code in his diary. A code, it turned out, that Marguerite had cracked.

“He would paint and draw his lovers and he certainly regarded them as muses, with all that that entails,” says Soussi. “But it should also be said that all the evidence points to these relationships not being just a one-way street and he maintained friendships and corresponded with many of his lovers for the rest of their lives.”

Although Scotland held many dark memories for McBey, the artist continued to visit and, perhaps surprisingly, maintained the Presbyterian faith of his childhood. He refused to work on Sundays throughout his career and in later years used his diary code to record not love affairs but instead messages praising and thanking God.

“He is buried overlooking the strait of Gibraltar,” says Soussi, “and he was the very definition of a man of the world, but for all that and for all his travels and his travails, a part of him remained a son of Aberdeenshire to the very end.”

Shadows & Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey is at Aberdeen Art Gallery, to 28 May. Shadows and Light by Alasdair Soussi is out now.

Man of the world … five highlights of the exhibition

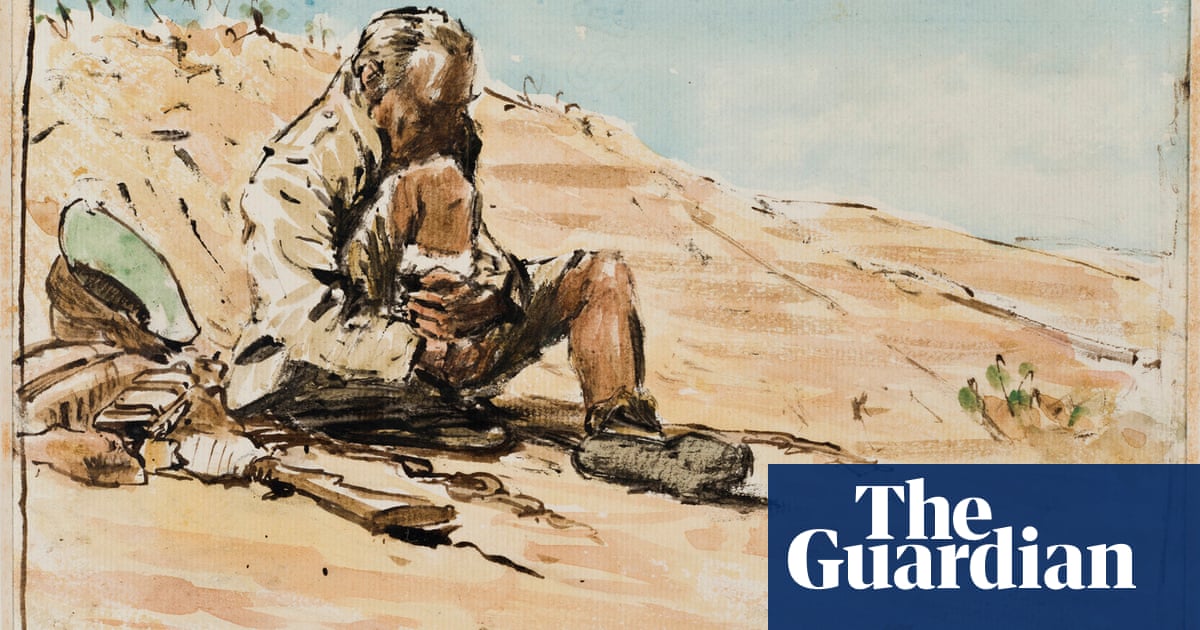

Soldier Resting, Birsu (1917) (Main picture)

For someone who was initially turned down for active service because of his poor eyesight, James McBey had an almost unrivalled front-row view of the first world war in the Middle East. He was with British general Edmund Allenby in Cairo, Alexandria, Damascus and Aleppo, and witnessed Allenby’s troops’ 1917 entry into Jerusalem, the first European – and in effect Christian – army to have occupied the city since the Crusades.

Portrait of Marguerite McBey (1950)

McBey’s wife is sitting in the garden of El Foolk – the Ark – their home in Tangier. The artist was endlessly unfaithful, but the two stayed married despite several separations. In the 40 years Marguerite lived after McBey’s death, she acted as a steward for his life and work as well as becoming a noted watercolour painter.

El Marrakeshia (1936)

McBey was endlessly absorbed by the light, colours and ambience of Morocco and would paint markets, street scenes, acrobats or, as here, the sex workers of Marrakech, complete with the sumptuous fabrics of their clothes. On the headstone of his grave in Tangier, “He loved Morocco” is inscribed in Arabic.

Dawn: The Camel Patrol Setting Out (1919)

This etching on paper achieved a record price for a modern print in the 1920s. It features an Australian camel patrol conducting reconnaissance in the Sinai desert. McBey travelled with the troop, recording his own first time on a camel as: “Little bit nervous, but after mounting felt all right. Does not appear so far from ground as I thought it would.”