Seventeen-year-old Mae is an excellent listener. In almost every other respect, the narrator of Nicole Flattery’s debut novel is a mess: she’s dropped out of school; she’s ignoring her mother; her nascent encounters with the adult world are bleak enough to give Holden Caulfield a run for his money. Chaos swirls around her, but she manages, somehow, to hold herself still at the centre of it: saying little, giving nothing away, but paying close attention. And it’s this capacity to listen – to receive rather than to transmit; to locate herself in the audience, rather than to launch herself on to the stage – that allows her to step into a role as a vital but invisible cog in what would become a world-famous machine.

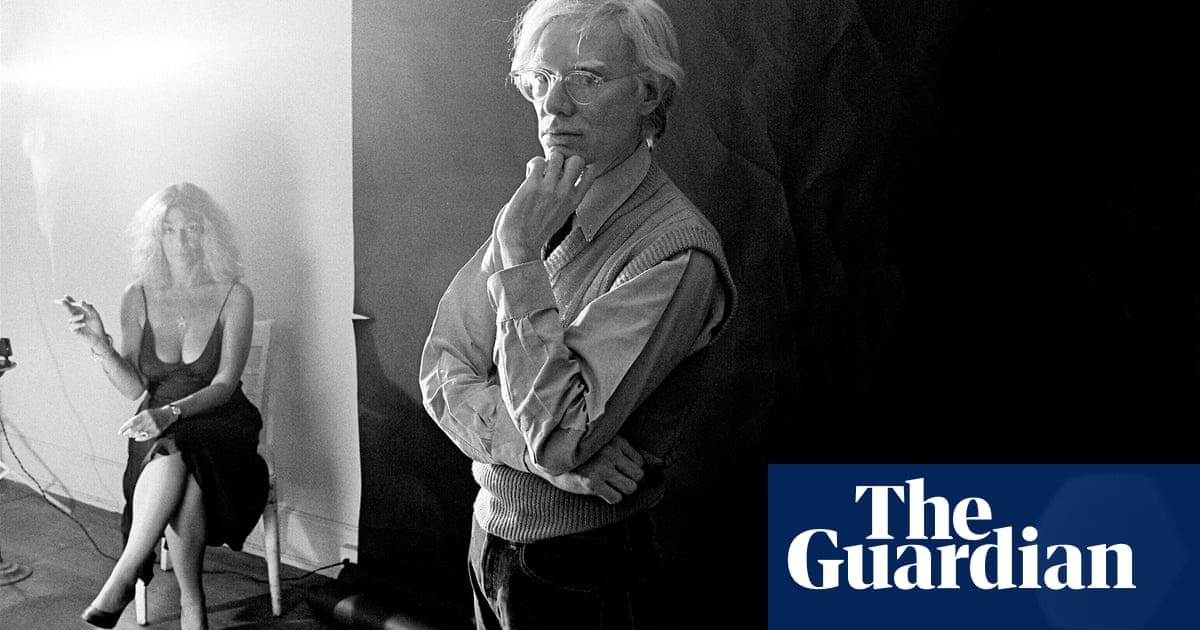

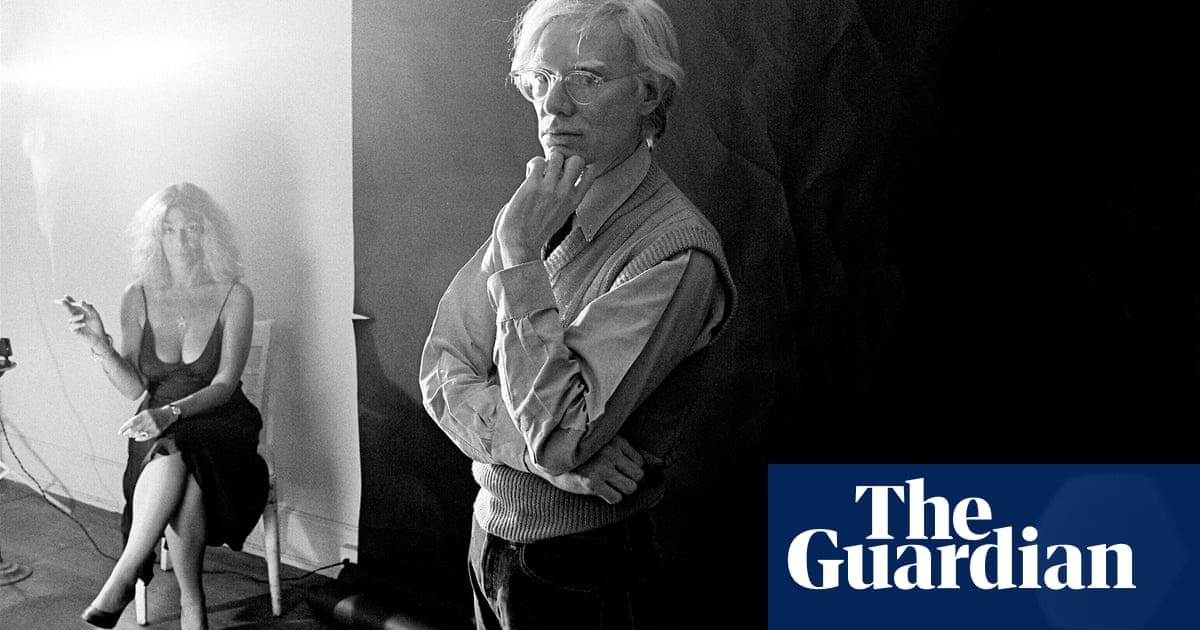

Nothing Special is set in the grubby avant garde of Andy Warhol’s Factory studio, which, in 1966, when the story kicks off, was establishing itself as an artistic and cultural force to be reckoned with. On the face of it, Flattery’s choice of time and place is unexpected: she’s strongly associated with the new wave of Irish literature, while Warhol and his Factory are as American, in their way, as apple pie. But those who’ve read her acclaimed 2019 collection, Show Them a Good Time, will realise at once that while the physical landscape of Nothing Special – the diners and department stores and “people disappearing into subway stations” – is quintessentially New York, the emotional terrain is all Flattery’s own. Mae and her new friend, fellow Factory worker Shelley, are cut from precisely the same cloth as the jaded, affectless women who populated Flattery’s short stories: they’re perceptive about the limits placed on female experience, but too disillusioned to do anything other than accommodate them; they yearn for significance but can find no way of attaining it. Mae and Shelley are charged with answering the Factory’s famous silver telephone, but the callers never ask for them.

Nowadays Warhol’s Factory is possessed of an almost mythic glamour: it sat at the nexus of art, celebrity and the 60s, and came to define all three. But in showing it to us through Mae’s eyes, Flattery reveals its fundamental utilitarianism: like a mid-century Dorothy, she twitches back the gaudy curtain and reveals the gears and levers. While Warhol’s superstars – Ondine, Susan, Edie – loll on viscose sofas, drift from party to party, bitch about each other, and occasionally smile, or frown, or cry for the camera, Mae and Shelley are engaged in real, recognisable labour. Their place of work may be filled with intoxicated bodies and “covered in demented silver paper, tacky and peeling”, but they “work efficiently and without passion”, keeping regular office hours. They sit at their desks; they put on headphones. They listen. And then they type.

What they are typing is 24 hours in the life of the Factory: Warhol made round-the-clock recordings of every conversation, every sigh and whisper, every siren, or slammed door, or struck match that was heard in the place over the course of a single day. It’s the job of Mae and Shelley – initially employed as all-purpose secretaries, then promoted to this special project – to transcribe the lot, and they approach their task with diligence, typing up everything, to the last creak and sniffle. All of this, by the way, really happened: the resulting manuscript was published as A: A Novel in 1968, with Warhol’s name on the cover. The typists who transcribed the pages were never credited; in fact, of the four women who did the work of turning Warhol’s concept into a reality, two have never been identified.

Into this dismal gap in the historical record, Flattery slips her two protagonists. As the title suggests, Mae and Shelley aren’t special: they just walked through the Factory door at the right moment. But special or not, they were there: they listened to every word the big shots uttered (and formed their own opinions on them); they took pride in their act of construction, their choice of nouns and adjectives. The project may not have been theirs, but the execution was. And just as importantly, perhaps, they were elsewhere, too: they went to the park; they had snippy rows over cups of coffee (Flattery has a fine ear for dialogue). They had lives beyond the Factory door. “I was still interested in them,” Mae says of the Factory stars, midway through her transcription, “but something else had crept in: an interest in myself. I put more and more of myself in the book – misspellings, pauses where there weren’t any, my own emphasis, my own in-jokes. I had to leave a mark. You couldn’t be around egos like that for so long and not develop your own.” In fitting her complex, heartfelt, vexing characters into the spaces left where the names of Warhol’s typists should have been, Flattery is finally giving those egos, or a version of them, a chance to tell their own story, in their own words.