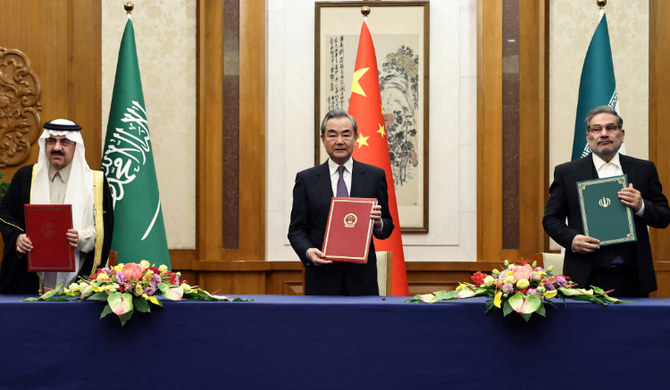

Like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Saudi-Iranian rivalry has always been perceived as central to the cause of regional peace and security. But is it, really? Could the decision by Riyadh and Tehran to restore their diplomatic relations, with Beijing’s help, contribute to real stability in the Middle East?

It is foolish to argue against political negotiations between adversaries. It is certainly better than fighting. But I believe this process is likely to generate limited regional security gains for three reasons. First, the Iranian regime’s unchanging penchant for expansionism. Second, China’s unwillingness and inability to play a more significant security role in the region. Third, Israel’s profound apprehensions about Tehran’s nuclear program.

Let’s start with Iran. The Islamic Republic is nothing if not pragmatic. But history has shown that it is also deeply conservative when it comes to its sectarian worldview and it is consistent with how it has pursued it. Those in Tehran driving Iranian foreign policy are not the diplomats, some of whom were involved in negotiating the latest accord with their Saudi counterparts. Rather, it is Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and, increasingly in recent years, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and those actors believe that Iran’s destiny is fulfilled only by spreading its Shiite ideals across the Arab-Muslim world, by force if necessary.

Had Iran not been diplomatically isolated and its economy in dire straits, it most likely would not have entertained any rapprochement with Saudi Arabia. Indeed, that is the pragmatic side of Iranian foreign policy. But the moment it reaps the benefits of this deal, Tehran will reveal its true character again and show little restraint in its regional approach. Iraq remains in Iran’s sights and the plan has always been to control Iraqi politics and resources through violence, intimidation and divide-and-rule tactics. Iran is not about to give up Yemen either, given its strategic location and proximity to global chokepoints.

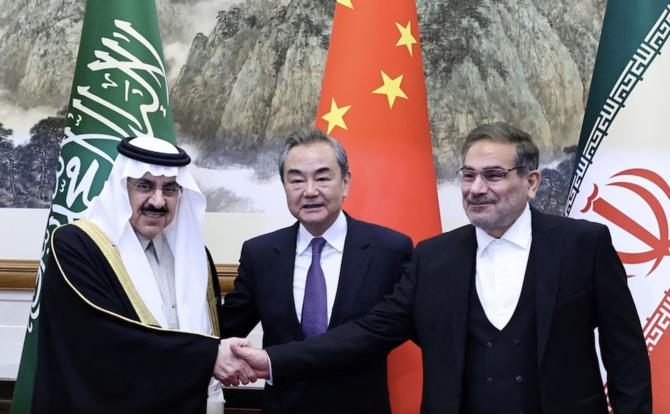

With regard to China, Beijing deserves credit for presenting itself as a power broker in a region that has traditionally been under US influence. But even the most amateurish observer of international relations knows that diplomacy with no teeth can be very short-lived.

The main reason why the US could enable historic Arab-Israeli peace agreements — first between Egypt and Israel and then between Jordan and Israel — was because it provided security guarantees to the negotiating parties. China has no interest in providing such guarantees to either the Iranians or the Saudis, because its main security investments reside in Asia. The Middle East is too far from home and the risk of overstretch is all too real for the Chinese. Beijing prefers to continue to free ride on American security and prioritize its economic and energy interests in the region.

Given that the understanding does not include Tehran’s nuclear program, this leaves a major ticking time bomb unaddressed

Bilal Y. Saab

So, when Iran reneges on its promises (it is a matter of when, not if) and threatens Saudi security again, China will be in no position to play any meaningful policing or deterring role. Can China expand its military presence in the Middle East? It can, to some extent. But does it want to, and can it replace the US as a security guarantor? I do not think so. For all the proclamations of the end of US influence in the Middle East, Washington is not about to surrender its powerful and unmatched military position in the region, mainly for broader geopolitical reasons.

Nothing will revamp regional security like a resolution of the challenge of Iran’s nuclear program. And there are no signs of progress. Israel is laser-focused on this matter and will do everything it can to stop Tehran from getting the bomb, even if it leads to regional war. For the Israelis, the possibility of Iran becoming a nuclear state is an existential issue. Given that the Saudi-Iranian understanding does not include Tehran’s nuclear program, this leaves a major ticking time bomb unaddressed.

Israel was hoping to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia, after it did so with the UAE and Bahrain in recent years, in an attempt to further isolate and build a regional defense architecture against Iran. But it is less clear now that Riyadh will risk its entente with Tehran by teaming up with the latter’s historical enemy.

Maybe that is a good thing, because perceptions of the Iran threat in Israel and Saudi Arabia are vastly different. Riyadh certainly worries about Iran acquiring nuclear weapons, but it does not see it as a mortal danger. Israel does, on the other hand, and, unlike Riyadh, is willing to use — and has used — military force to avert such a scenario. For Riyadh, expanding the Abraham Accords is still an option or an insurance policy, but only if Iran goes back to its old ways and bullies its neighbors again, which I believe it will.

Saudi Arabia’s motivations for the deal with Iran are largely security-based. Iran’s are economic. There is a disconnect here, for sure. In addition, there is no strategic parity between the two sides. The Saudis fear the Iranians and are the militarily weaker party; the Iranians do not feel threatened by the Saudis and are the aggressor. This drastic imbalance is a bad foundation for a productive security dialogue.

Perhaps with some luck and effective communication between Tehran and Riyadh, this new deal might temporarily bring down the bilateral temperature, but it is not enough to advance regional security.

Almost four-and-a-half decades of the mullahs’ rule in Tehran have shown that Iran, while pragmatic with its methods, is committed to regional domination. China has leverage over Iran because of oil politics, but it is incapable of changing Tehran’s ways. Israel, meanwhile, is inching closer to bombing Iran’s nuclear infrastructure.

The Saudi-Iranian understanding is welcome news for a region looking for any kind of optimism, but security in today’s Middle East is a lot more multifaceted than in the past and thus will require much more than an uncertain transactional accord between Riyadh and Tehran.

• Bilal Y. Saab is Senior Fellow and Director of the Middle East Institute’s Defense and Security Program.