In early 2003, I was living in Cairo and carrying out research for my doctoral dissertation on a famous Iraqi poet who lived in my hometown, Baghdad, in the 10th century. But I was increasingly anxious about the Baghdad of the 21st century.

Like millions of people across the world’s major cities, I took part in the massive protests against the then imminent invasion of Iraq. Tahrir Square, the centre of the revolution that toppled the Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, eight years later, swelled with tens of thousands of angry Cairenes. We headed to the nearby US embassy, but the riot police pushed us back with batons.

The drums of war had been beating for months. While there was popular opposition throughout the world (there were coordinated protests in 600 cities in February 2003), the war’s architects, merchants and cheerleaders were vociferous and dismissive of those of us who warned against the catastrophic aftermath for Iraqis and the region, labelling anyone who questioned the war a supporter of dictatorship.

Many of us who had stood against Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship and his regime wrote and spoke against the planned invasion for what were already obvious reasons. We challenged the false narrative of Iraq possessing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). After 700 inspections, Hans Blix, the head of the UN’s weapons inspectors, and his teams had found no weapons in Iraq. The “mushroom cloud over Manhattan” that Condoleezza Rice warned about was a propaganda cloud to intensify hysteria. George Bush, after all, had reportedly decided to strike Iraq the week after 9/11.

The corporate mediascape in the US was an echo chamber for state propaganda. It wasn’t just the Manichaean worldview of post-9/11 national security hysteria, but a deep-seated colonial mentality – variations on the white man’s burden. An analysis of US TV news in the few weeks preceding the invasion found that sources expressing scepticism of the war were massively underrepresented. The media performed its function quite well in manufacturing consent and parroting official propaganda. In March 2003, 72% of American citizens supported the war. We should never forget this. (Up until 2018, 43% of Americans still thought it was the right decision.)

In Cairo, I watched as the US began its “shock and awe” campaign – a terrifying rain of death and destruction on Baghdad. Poetry was my refuge and the only space through which I could translate the visceral pain of watching the violence visited on Iraq and seeing my hometown fall to an occupying army. Some of the lines I wrote in the early days of the invasion crystallise my melancholy:

The wind is a blind mother

stumbling

over the corpses

no shrouds

save the clouds

but the dogs

are far quicker

The moon is a graveyard

for light

the stars are women

wailing.

Tired from carrying the coffins

the wind leaned

against a palm tree

A satellite inquired:

Whereto now?

The silence

in the wind’s cane murmured:

“Baghdad”

and the palm tree caught fire.

I had always hoped to see the end of Saddam’s dictatorship at the hands of the Iraqi people, not courtesy of a neocolonial project that would dismantle what had remained of the Iraqi state and replace it with a regime based on ethno-sectarian dynamics, plunging the country into violent chaos and civil wars.

Four months after the invasion I returned to Baghdad as part of a team to film About Baghdad, a documentary about the war and its aftermath. The chaos was already evident. One of the tens of interviews we conducted that simmering July was with a man who was optimistic about the occupation. “But a lot of these people the US is bringing to rule are thieves and crooks,” I told him. “My son,” he replied, “if they steal half of our wealth we’ll still be better off with the other half.” I remember that conversation whenever I read about the astronomical figures and massive corruption of the post-2003 Iraqi regime.

Some Iraqis we interviewed were obviously seduced by or took American promises seriously. Others were too drained and desperate after more than a decade of another war in the form of the genocidal sanctions from 1990 to 2003, and thought “so be it”. There were those, inside and outside, who knew that this was colonialism and stood against it. But there were colonised minds aplenty. A group of Iraqi writers, poets and professionals later penned a thank you letter to Bush and Tony Blair.

When the nonexistent WMDs were not found, there was a shift in the propaganda narrative to “democracy” and “nation building”. The war’s lethal effects were rationalised as the necessary birth pangs for a “new Iraq”. The country would be a model in the Middle East for what global capital and free markets could offer. But promises and plans of reconstruction became black holes for billions of dollars and fuelled a culture of corruption. American war advocates themselves benefited from the war.

The invasion did bring about a new Iraq. One where Iraqis have daily encounters with the consequences of the war on terror: terrorism. The “new Iraq” that the warmongers promised did not bring Starbucks or startups, but car bombs, suicide bombings, al-Qaida and later Islamic State – the latter hatched in the US’s own military prisons in Iraq.

In the first few months of the invasion I saw a report on a US TV channel showing an embedded reporter with American soldiers in a Humvee about to leave a base near Baghdad on a patrol. When the Humvee exits the gate, one of the soldiers tells the reporter: “This is Indian country.” This, I learned, is a common, although unofficial, term, used in the US military in Iraq and Afghanistan to refer to “hostile and lawless territory”. NBC’s Brian Williams recounted how a US general giving him a tour in Iraq used it too.

The colonial frame and embedded notions of white supremacy illuminate how most Americans, military or civilians, can view, make sense of, or simply ignore what their government does. It was another frontier between the forces of an advanced and well-meaning civilisation and a hostile and violent culture, ungrateful for what was offered and burdened by its violent past.

The Iraq that the invasion begat must be one of the most corrupt states in the world. Iranian-backed militias (whose rise was a byproduct of the dynamics the invasion created) dominate the lives of Iraqis and terrorise opponents. They helped the regime brutally crush the 2019 uprising, which was spearheaded by Iraqi youth who rejected the political system that the US installed. One of their slogans in the uprising’s early days was: “No to America, no to Iran!”

Today, there are 1.2 million internally displaced persons in Iraq, most of them in camps. An estimated 1 million Iraqis have died, directly or indirectly, as a result of the invasion and its aftermath. It is not just the body politic that is disfigured, but the body itself: the depleted uranium left by occupying forces has been connected to birth defects still today, especially in Fallujah, where there are also elevated rates of cancer.

Last December, the US navy proudly announced that its next amphibious assault ship will be named “Fallujah”. This may seem shocking, but it is part and parcel of settler-colonial culture. Apache, Lakota, Cheyenne and other names of native tribes still suffering the ongoing effects of American settler-colonialism are now the names of lethal weapons. A million lives later, this is what American terrorism has done to Iraq.

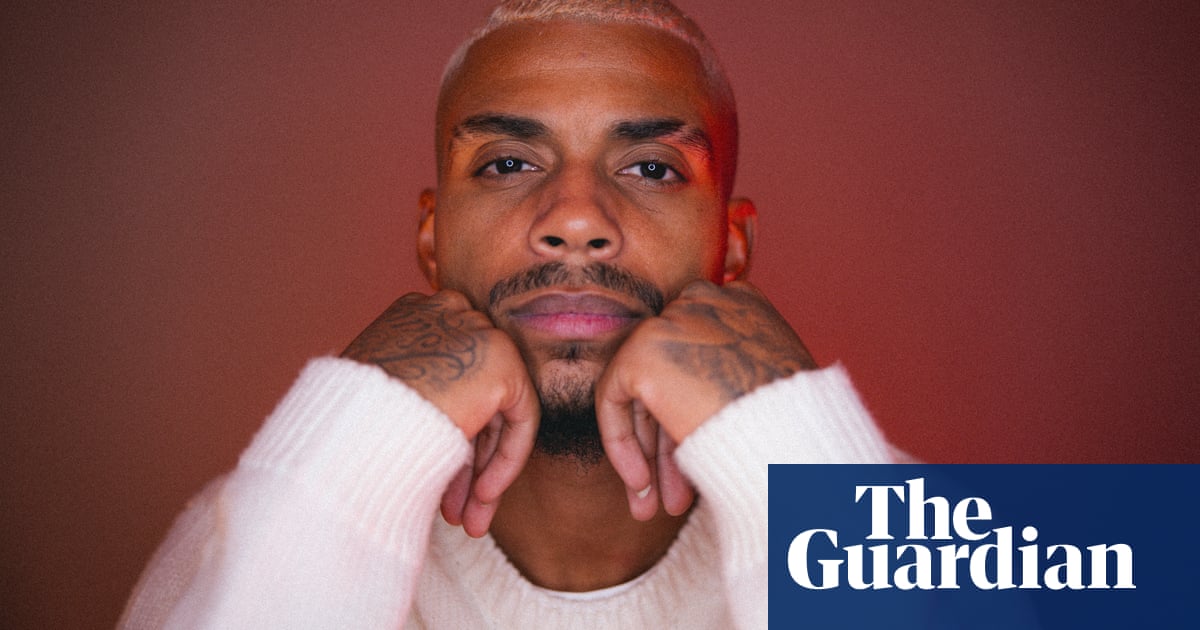

Sinan Antoon is an Iraqi poet and novelist. His most recent work is The Book of Collateral Damage