One of the earliest photographs of J Edgar Hoover shows him aged 17, standing tall and proud in the starched uniform of a high school cadet. At first glance he is a figure of innocence: a Hoover without victims. But the fact he wore such a uniform to teach Sunday school classes is indicative of a young man on a divine mission.

“Sunday school was boot camp, the training ground in the battle for the soul of the nation, and Hoover dressed the part,” writes Lerone Martin, academic and author. “It was 1912, and J Edgar Hoover was his own man: a soldier and a minister fighting the good fight with military precision. It was a lifelong commitment, an unceasing crusade to keep America a white Christian republic.”

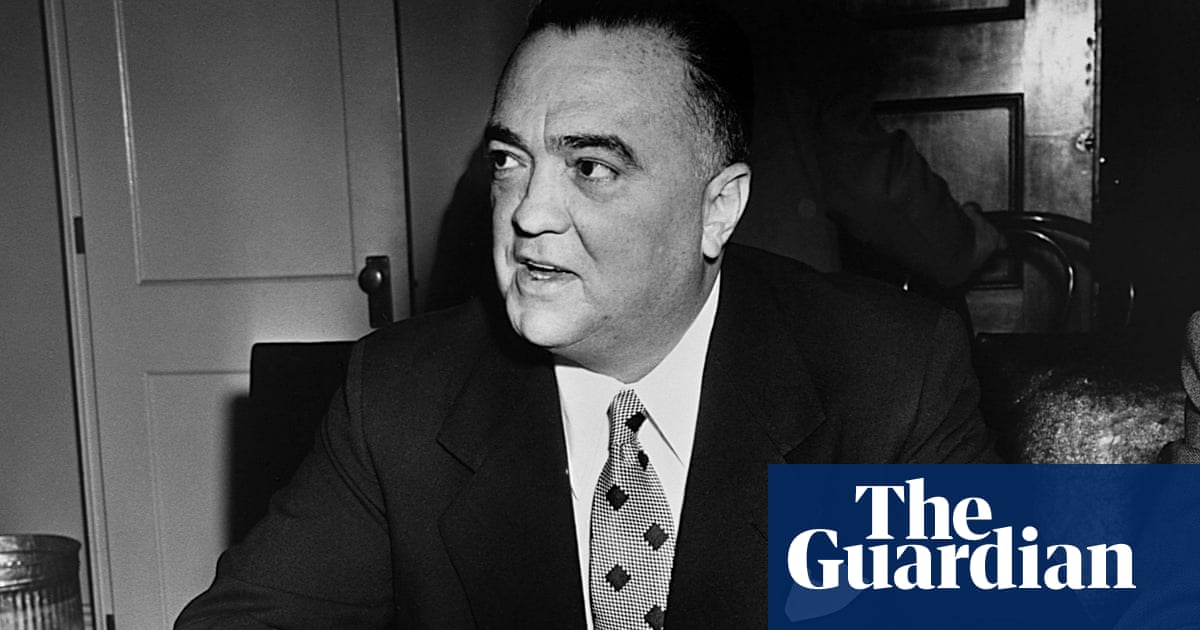

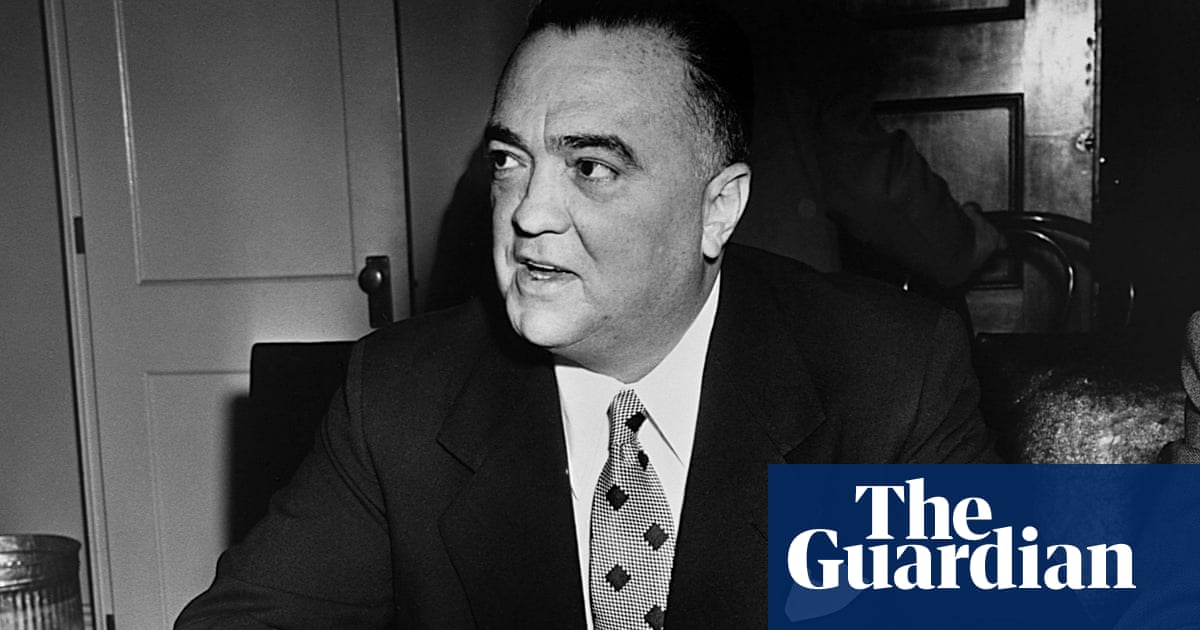

Hoover would serve as director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1924 until his death in 1972, spanning eight presidents (four Democrats, four Republicans) over nearly half a century. He took on mob bosses and organised crime, established a centralised fingerprint database and implemented scientific techniques such as forensic analysis.

Hoover was a workaholic who devoted his life to the agency. The FBI headquarters on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington is named after him, his desk has pride of place at the National Law Enforcement Museum and Leonardo DiCaprio played him in a biopic directed by Clint Eastwood.

But Hoover’s legacy has aged about as well as Gone With the Wind’s. He was notorious for strong-arm tactics, political manipulation and disregard for civil liberties. He used the FBI’s extensive intelligence-gathering capabilities to monitor political dissidents, civil rights leaders and other groups he deemed a threat to national security.

President Harry Truman, alarmed by Hoover nosing into Americans’ sex lives, warned: “We want no Gestapo or secret police. The FBI is tending in that direction.” Biographer Beverly Gage has called him “the 20th century’s single most effective foe of the American left”.

Martin now delivers a fresh perspective. In an elegantly written book, The Gospel of J Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism, he makes a persuasive case that Hoover was a white Christian nationalist and convenient ally for evangelicals, embedding race and religion in the foundations of the national security state – and allowing white supremacy to fester to this day.

Previous studies of Hoover and the FBI have rarely considered his faith or its influence on the nation, Martin argues. “We imagine the FBI – I did when I began – as spying on [journalist] Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr, Fannie Lou Hamer and all these religious communities,” the 43-year-old says by phone from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California.

“But we never really considered: what about the other expressions of Christianity in America that saw the FBI as a saving grace? Because of the emphasis on surveillance in the FBI, we’ve been slow to recognise that there’s also a form of cooperation and partnership, that the FBI wasn’t doing everything cloak and dagger behind the scenes. There were a number of things the FBI did out in front and they were heavily supported by the American public.”

Martin outlines how the FBI sent agents to services of worship that established religious identity as synonymous with American citizenship; the FBI worked with white evangelicals to promote Christian nationalism as the only form of religion that would protect the US during the cold war; and the FBI policed other forms of religion, for example by persecuting King and aiming to discredit the civil rights movement.

Hoover was the ideal enforcer. He had been raised in the Presbyterian church and taught Sunday school as a teenager. It was an assignment he took earnestly and seriously: his diary was filled with Sunday school lesson plans.

Martin says: “When he became head of the FBI in 1924, he made his agents sign a law enforcement pledge which explicitly said they would conduct themselves as ministers seeking to give aid and advice to those who need it, and as soldiers waging warfare against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

“Hoover saw himself throughout his life as this minister and soldier. In fact, he claimed that he had planned to go to seminary and become a minister but his father had fallen ill, was labelled as melancholy at the time – what we know now today as more likely depression or mental illness – so Hoover felt compelled to go and make money.

“He worked during the day and went to law school at night and took over the FBI and tried to baptise the FBI in his own image and make it a place where folks saw themselves as not just working for the federal government but actually working for God.”

Hoover grew up in racially segregated Washington DC and was more than ready to uphold white supremacy in the US. “Hoover did believe that white people were superior and that African Americans were innately inferior. He refused to hire African American agents.

“He did all that he could to put up the charade that he wasn’t racist, including having Ebony magazine in the 40s do a story called Negroes in the FBI but in reality all the gentlemen featured in that story were not doing any crime fighting, any investigation; they were all valets for when he came to the city.”

The author adds: “He never saw African Americans as being full citizens. It was something that Hoover believed African Americans needed to work towards in a collective sense, that they needed to show themselves worthy of citizenship, whereas for white Americans, native-born white Americans in particular, that just ‘came naturally’ for them.

“For him, that was innate, whereas he never considered the sociological factors that kept African Americans at a distance in many ways from economic security, housing security, educational access. Hoover saw these things as sort of natural as opposed to created and so, in that sense, he was certainly a white supremacist and a racist.”

Hoover and the white evangelical movement made a marriage of convenience. The FBI gained ministers it believed would be useful in its crusade against a Protestant establishment that was critiquing capitalism and advocating for civil rights. The evangelicals, still considered outsiders, sensed an opportunity.

“Folks like Billy Graham and others saw themselves on the outside. At a time when we’re going through an existential crisis, if you will, and battle with communism, having the endorsement of the FBI director provided them with an inside track to broader American acceptance and institutional and social power.”

Drawing on newly declassified FBI documents and memos, Martin tells how FBI agents attended spiritual retreats and services while prominent figures such as Billy Graham and Fulton Sheen incorporated Hoover’s words and perspectives into their sermons.

The author says: “Ministers hosted a special FBI worship service in which ministers and church members valorised the FBI as God’s protective force, protecting the country from communism, protecting the country from subversion and crime.”

Meanwhile, Hoover wrote essays for Christianity Today magazine. “Americans wrote to the FBI in droves requesting copies of the essays and ministers wrote in to the FBI, bragging about not preaching their own sermons, but taking Hoover’s essays into their pulpits and just preaching these essays from their pulpits. We can see the large support Hoover received.”

Martin finds a neat metaphor at the Capitol Hill United Methodist church, where in 1966 a group of white evangelicals dedicated a stained glass window to Hoover – their chosen vehicle for leading the country towards God and away from godless communism.

Yet for all his piety, Hoover was not an evangelical himself. He never married or had children. He did have a long relationship – never acknowledged as romantic or sexual – with his deputy Clyde Tolson. They dined together, went on holidays together and are buried a few yards apart. Hoover was a notorious homophobe who backed the “Lavender scare”, which saw dozens of gay men and women fired from government jobs.

Martin comments: “I don’t know if Hoover and Clyde Tolson ever were sexually active, but what we do know points to a beautiful domestic partnership. It does seem it’s very possible. Psychology and history tells us that it’s often those who are protesting extremely loudly as it relates to queerness are battling something inside beyond just concerns about other folks being queer. Oftentimes it’s something that’s going on inwardly. As we think about white evangelicals in our country and our history, that has been the case.”

Hoover’s unconventional domestic arrangements were hardly in sync with the conservative family values preached by Graham and others. But it would not be the last time that evangelicals proved willing to embrace an imperfect messenger, compromising their stated morality and theology in return for power.

Martin writes in the book: “Every generation turns to an ascendant white male politico of the era – Reagan, Trump, and so on – and, like John the Baptist, they ask, ‘Are you the one, or should we expect someone else?’ Evangelical political ingenuity constantly searches and finds its political champion, by any means necessary. This pragmatic ‘ends justify the means’ ethos … remains a robust tradition within the movement.”

Hoover has been dead for more than half a century. Yet the building that bears his name is still a bastion of whiteness; in 2021, just 4% of special agents were Black. On 8 March, Congressman Jamie Raskin, making the case for a new FBI headquarters in his home state of Maryland, said: “A Maryland FBI headquarters in the national capital region’s only majority-Black jurisdiction would mark a defining new start for an agency whose history in the last century was defined by Hoover-era racism.”

Martin, who is director of the Martin Luther King Jr Research and Education Institute and associate professor of religious studies at Stanford, says: “If they’re serious about making the FBI an agent of forming a more perfect union, they’ve got to take into account how the bureau and its culture has been riddled with white Christian nationalism in the past. There needs to be an intervention or this perhaps can continue unabated within the FBI.”

The Gospel of J Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism is published by Princeton University Press ($29.95)