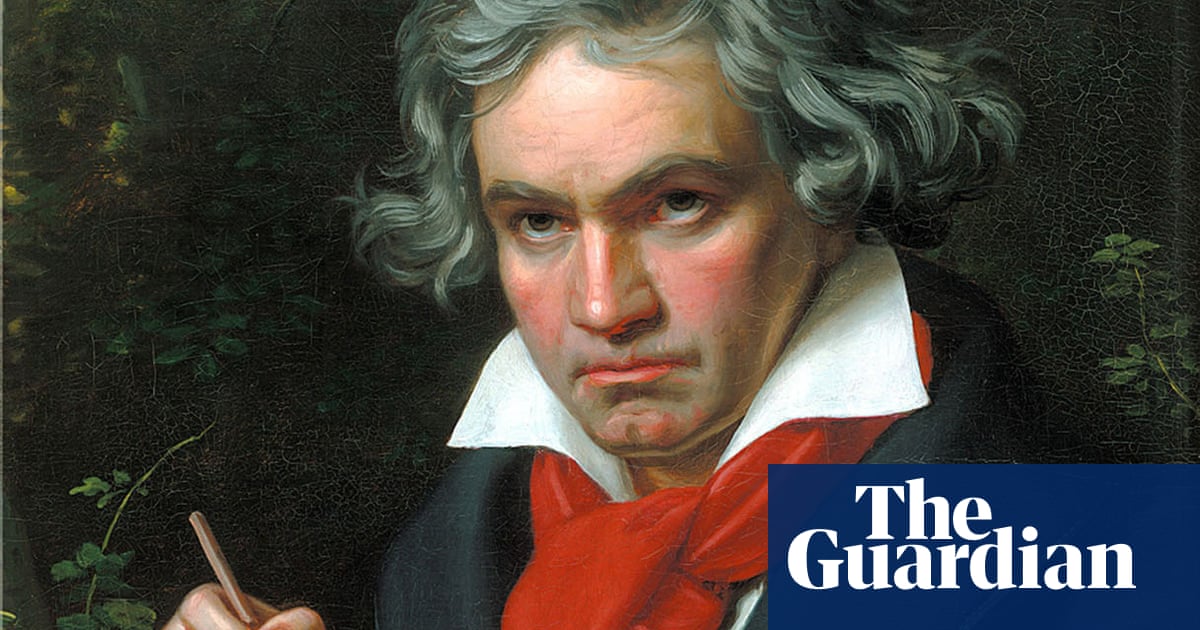

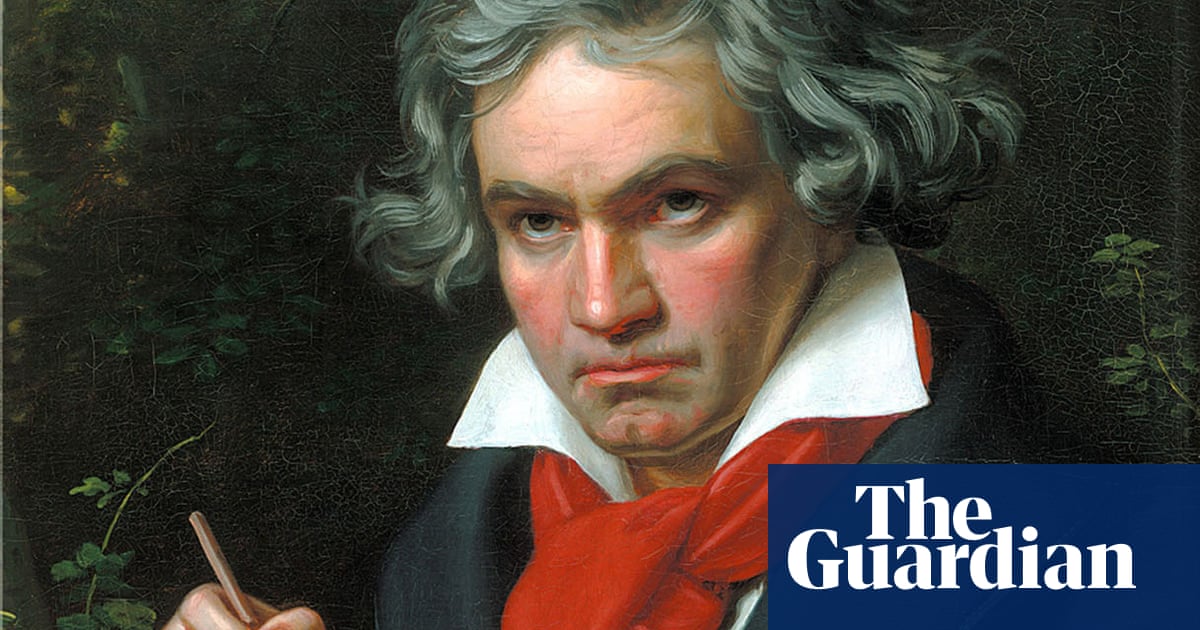

When an autopsy was carried out after Ludwig van Beethoven’s death in 1827, his liver was found to be “beset with nodules the size of a bean”. Now researchers say the cause may not have been alcohol consumption alone, with a genetic analysis revealing the great composer experienced a hepatitis B infection and was at high risk for liver disease – the condition generally thought to have killed him.

Tristan Begg, first author of the research from the University of Cambridge, said Beethoven had been extremely sensitive in his lifetime about suggestions he was a drunkard.

“We don’t exactly vindicate him, but I think the fact that there’s a genetic risk, and possibly hepatitis B – and for who knows how long – I would hope actually [presents] a bit of a paradigm shift away from the preoccupation with alcohol,” said Begg.

“If anything it would have taken less alcohol to do the same amount of damage than we would have earlier assumed.”

Begg and colleagues came to their conclusions after studying eight locks of hair attributed to the German composer and pianist to shed light on his health problems.

Beethoven was born in 1770 in Bonn and died in Vienna aged 56. He suffered progressive hearing loss, which began in his mid to late 20s and led to him being functionally deaf by 1818.

Genetic analysis revealed five of the locks were from the same individual, had damage consistent with dating from the early 19th century, and very probably came from the composer – with two having a well-recorded chain of custody.

One of these, known as the Stumpff lock, was attached to a letter from the harp and piano-maker Johann Andreas Stumpff dated 7 May 1827 – just a few months after Beethoven’s death.

The letter contained a poem: “The head, these hairs have grac’d lies low; But what it wrought – will ever grow,” noting the head was that of Beethoven.

Of the other three samples, one lacked sufficient DNA preservation for a conclusion to be drawn, while two were inauthentic.

The latter included a lock of hair allegedly cut from Beethoven’s head the day after his death by the musician Ferdinand Hiller, with the new analysis revealing this “Hiller lock” was actually from a woman, possibly of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

That is significant as previous analysis of this lock had revealed the hair contained high levels of lead, suggesting Beethoven’s health problems, hearing loss, and death might have been caused by, or at least linked to, lead poisoning. It also raises questions about whether Hiller did cut a lock from Beethoven, and if so, what happened to it.

Begg and colleagues carried out further genomic analyses of the Stumpff lock to investigate whether the composer’s DNA held clues to his ill-health.

While the team say their results cannot rule out a genetic contribution to Beethoven’s progressive hearing difficulties, they found no significant predisposition.

Nor did the analysis offer clues to Beethoven’s gastrointestinal complaints, which included diarrhoea and abdominal pain, revealing he did not have the classic genetic variants expected for lactose intolerance or coeliac disease.

While some experts have previously suggested he had irritable bowel syndrome, the new research suggests Beethoven had a low genetic risk of the condition. However, Begg stressed that environmental factors can play a key role in who develops IBS, while only a small proportion of its genetic risk factors are known.

Significantly, the work casts new light on Beethoven’s death, revealing the composer had a strong genetic risk for liver disease and had experienced a hepatitis B infection.

“Alcoholic liver disease seems to be the most favoured explanation. But then that’s been the only known risk factor for 200 years,” said Begg.

“Some form of viral hepatitis has been very frequently speculated, but there’s been no proof. Now there is proof of hepatitis B specifically,” he added.

Begg said these factors meant Beethoven’s risk of liver disease was probably increased. Indeed, when the team analysed data from the UK Biobank project from men of a similar age to Beethoven and with the same genetic risk factors and alcohol consumption, they found one in five had some form of cirrhosis.

Prof Barry Cooper, a Beethoven scholar at the University of Manchester who was not involved in the work, said he had always been suspicious of the lead poisoning theory.

Cooper added that his book Beethoven: An Extraordinary Life mooted the possibility of the composer having had viral hepatitis, but that Beethoven’s alcohol consumption would almost certainly have played a role in his cirrhosis, noting his average intake could have been more than one bottle of wine a day, which would be enough to damage the liver of a susceptible person.

“It’s good to know that this suspected susceptibility has now been confirmed genetically, along with the suspected hepatitis,” Cooper said, adding that the main cause of Beethoven’s gastric problems was probably poor hygiene.

Beethoven himself was keen for his ill-health to be made public after his death, requesting in his Heiligenstadt Testament that his disease be described.

But what would the great composer have made of the new findings?

“I think he probably would have appreciated commitment to tell the truth,” said Begg. “We have certainly really tried our best.”