In 2014, the Irish Times ran a profile of the film-maker Vivienne Dick with the headline: “Stifled in Ireland, celebrated in New York.” As an encapsulation of her formative years as an artist who found her calling in exile, it was blunt but pretty accurate. “There was nothing for me in Ireland back then,” says Dick of her youth in the 1960s and early 70s. “It was not an attractive place because, as a woman, you were essentially treated as a second-class citizen. You could train as a teacher, but that was about it. I remember I bought a camera, but there was no way to even get on a course.”

Having relocated to New York by the mid-70s, after various overland adventures that took her to Pakistan, Nepal and even Kabul, she found herself instinctively drawn to Manhattan’s edgy, bohemian downtown scene, where would-be artists, musicians and writers had colonised the low-rent apartments and makeshift studios of what was then a deprived, drug-ridden neighbourhood. There she hung out with many of the characters who would go on to define Manhattan’s legendary post-punk No Wave movement: the likes of Lydia Lunch (of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks), Pat Place (Bush Tetras), James Chance and Adele Bertei (the Contortions). Her films capture these maverick outsiders at the very moment the scene congealed into a fleeting but incredibly fertile cultural moment – all attitude and dissonance – that still resounds today.

And it was there she met the photographer Nan Goldin, a kindred spirit who, 40 years later, remains a close friend. “She was wearing a green and orange mini dress,” Goldin recalled recently, “and I thought this is one of the most beautiful people I’d ever seen. It was friendship at first sight.”

Dick’s immersion in that moment was transformative. “Coming from rural Ireland, it was like a new world to me,” she says. “And in retrospect, I was really lucky, because people were trying out all sorts of different approaches to music, dance, theatre. I absorbed it all without any conscious intention of becoming a film-maker.”

This, perhaps, is what makes Dick’s early films so intriguing: the sense that, like her subjects, she is mapping out new territory – but quietly and tentatively, as both an insider and an acute observer. “Though she worked for a time with Jack Smith, I don’t think Vivienne was a student of influential underground film-makers like Kenneth Anger or Jonas Mekas,” says John Marchant, whose eponymous new Brighton gallery opened at the weekend with an exhibition of Dick’s photographs alongside a recent film, Red Moon Rising. “She just did it by instinct, treading a line in her early work between documentary and narrative – and, in the process, evoking an acute sense of a culturally important and wildly innovative time and a place.”

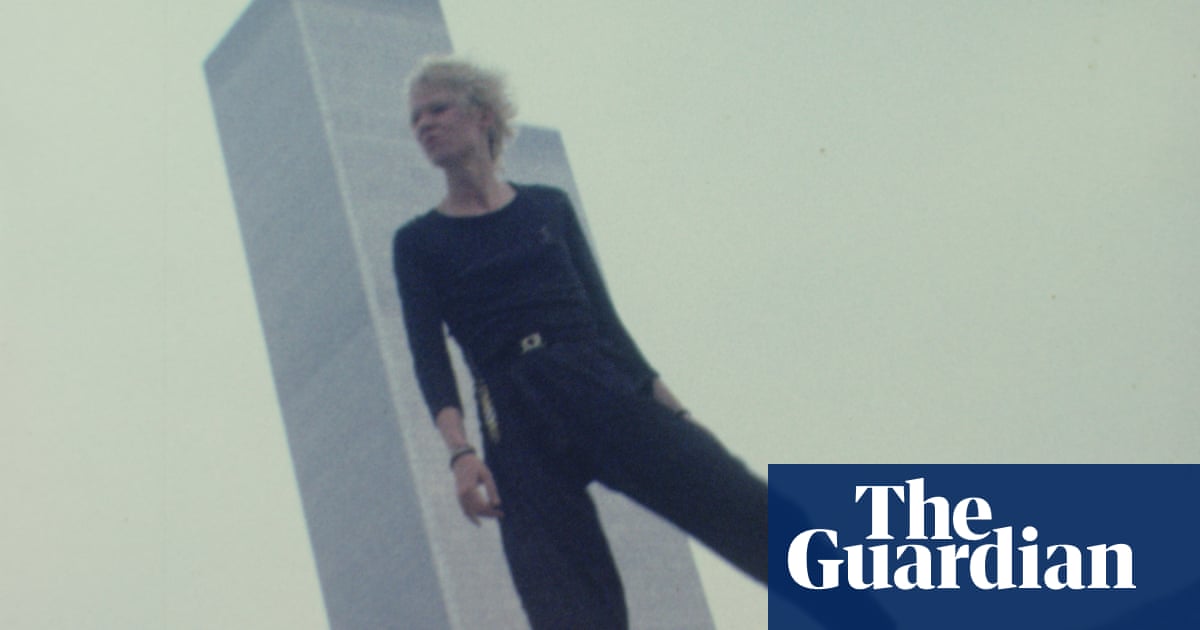

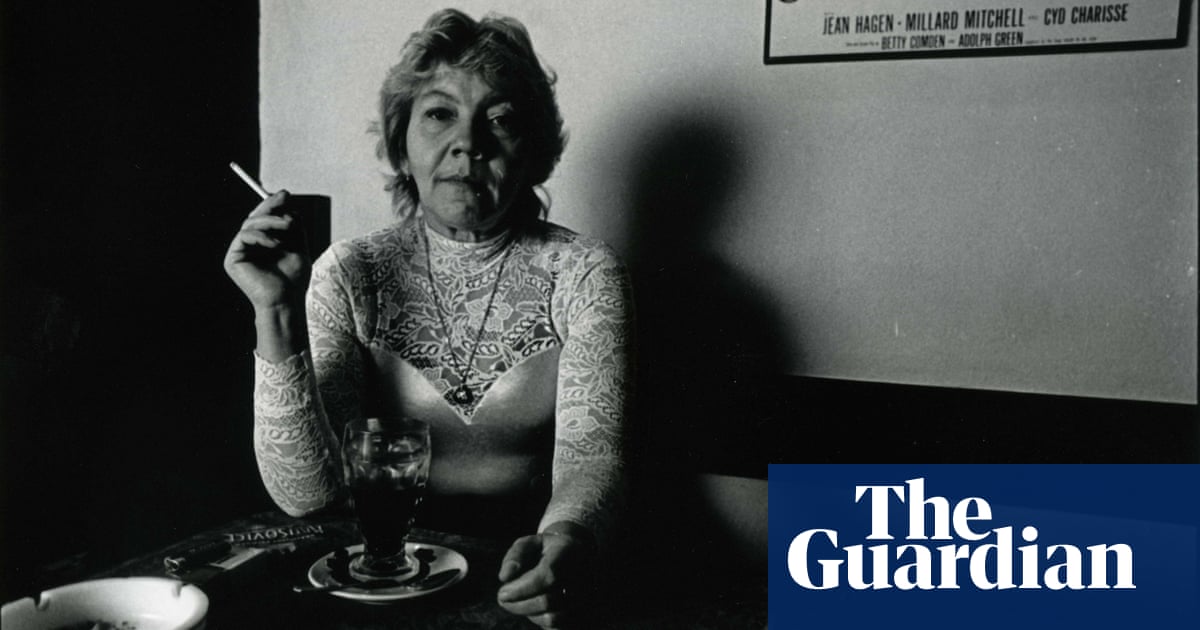

For 1978’s Guerillere Talks, her earliest work, she lets some of the leading women of the No Wave movement self-dramatise themselves and their creative lives-in-progress on grainy Super 8. “It’s as if she just pressed ‘Go’ on the camera and let it roll, then gaffer-taped six rolls of film together,” says Marchant, who has known Dick for more than 20 years and also worked as a studio manager for Goldin. The end result, though, has a raw, poetic intimacy that perfectly captures the iconoclastic spirit of the time.

In one reel, a young and pouty Lydia Lunch, posing in a rubble-strewn tenement as an exasperated street brat, complains in her affected adolescent drawl: “I gotta hang out on fire escapes – it’s not fun to be a teenager any more.” In another, an impossibly cool scenester, Anya Phillips, lipstick smeared across her cheekbone like a switchblade slash, simply poses with a cigarette, bored and beautiful.

“I picked women mainly from the music world,” says Dick, “and I gave them the freedom to do what they liked while the camera rolled.” She remains in touch with many. “It was a tough time and people tend to put a glaze on it as time goes by. But it was also an incredibly exciting, vibrant time and I picked up on that. I felt like I was living in the centre of the world.”

Now in her early 70s, Dick grew up in the fishing village of Killybegs in Donegal. Having returned to Ireland in the mid-90s, after almost a decade in London, she now lives in Inchicore, a suburb of Dublin. Throughout, she has continued to make films. “I never gave up,” she says, “even though there were big gaps where I was lost with it and thinking, ‘What am I doing?’ It was all very fast and urgent in the beginning in New York, then in London it was slow, but now it feels about right.”

Her more recent work is informed by her longtime feminism as well as a new sense of urgency about the fate of the planet and, as she puts it, “a belief that it doesn’t have to be this way, that we don’t have to be ground down if we can imagine another world”.

Red Moon Rising, as the exhibition is called, features a selection of vibrant colour stills from her early Super 8s, including Guerillere Talks, She Had Her Gun All Ready and Liberty’s Booty, alongside a screening of the 2015 film that gives the show its title. The last is a world away from her early work, a richly hued metaphorical performance piece that, she says, “explores themes of female power, ancient power and the nature of ancient, invisible time”.

It features often elliptical contributions by female Irish artists she has befriended, including a young rapper who goes by Temper-Mental MissElayneous, and a voice artist, Jennifer Walshe, whose inchoate outbursts have an unsettlingly visceral charge. “Language is power,” says Dick, “and it’s often about who gets to speak. But I’m also acknowledging that there is so much reality that cannot be put into words.”

In many ways, Dick’s films have moved from addressing her immediate milieu – the energy of a pivotal cultural moment in late 70s New York – to the ebb and flow of deep time, the traces of ancient myth and ritual that still resonate in the elemental landscapes of Ireland’s ancient sites. The Irreducible Difference of the Other, a film from 2015, shows her conceptual ambition. It features the Franco-Irish actor Olwen Fouéré, evoking the spirits of the transgressive French writer and actor Antonin Artaud, and the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

Artaud – who travelled to Ireland in 1937, convinced he was returning the sacred “Staff of Jesus” to its spiritual home – seems an abiding presence in her work. “He believed theatre is about waking people up,” she says. “I think we need to get back to that idea of art as transformative, but we also need to become more aware of our deep relationship to the Earth. We are so distracted now by technology and our brains so colonised by capitalism, that it is hard for us to sit still and do nothing.”

For all that, Dick is still active, engaged and seems finally at home in the country she fled as an innately curious but stifled young woman. “It’s a great place to be living,” she says, “and I still have that interest I always had in the world around me. It’s by the by that I have somehow become a cult figure. What’s more important to me is that I make the most of the time I have left on this planet.”

Red Moon Rising: Early and late Work by Vivienne Dick is at John Marchant Gallery, Brighton, until 6 May