Southend-on-Sea in the 90s was a mess: a tatty, former picture-postcard town where seaside dilapidation washed up against homogenous suburbs. Its claim to fame was the world’s longest pleasure pier: a path to nowhere stretching into the Thames estuary mudflats. Culturally, things followed suit. The wider area dined out on its reputation as the birthplace of Depeche Mode, while its role as the centre of pub rock was not – at least prior to the canonisation of Wilko Johnson – something anyone under the age of 40 would boast about.

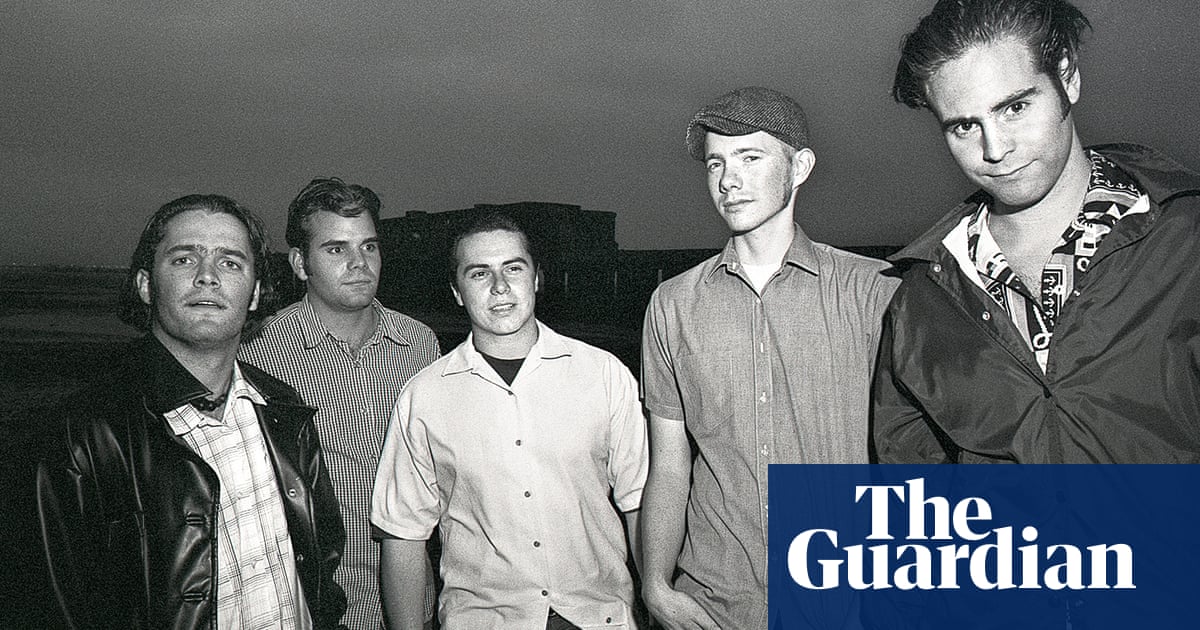

But amid tribute acts playing sad seafront venues, by 1994 there existed a vibrant, subterranean pocket of punk with two bands at its core: metalcore bulldozers Above All and the sharp, dissonant post-hardcore act Understand. These acts helped nurture and inspire a small circle of similarly minded bands: Outbreak, Pepperman, Stands to Reason, Raiden and a revivified Cynical Smile. The scene even stretched beyond Southend: Understand briefly stood on the brink of glory until an ill-fated dalliance with a big label prompted a backlash among their peers and ultimately led to their breakup before they could release a second album. But 25 years later, their album Real Food at Last is finally seeing the light of day (on the major label-backed Rise Records, no less).

“I think the ‘why’ of Understand could be distilled to something as simple as meeting half-decent people in a town that’s not full of decent people,” says the band’s guitarist Rob Coleman. “You start putting on your own shows and that attracts a certain type of person and even if you don’t know the entire audience you know you’re not going to be glassed. In Southend, that felt like no small achievement.”

This burgeoning scene had its champions, with Kerrang! comparing Southend to punk rock meccas New York, LA, Seattle and Washington DC. “Obviously it wasn’t entirely serious but even being on their radar felt like a victory,” says Coleman, while hinting at something of a bunker mentality. “We initially focused on being more of a ‘London band’ until we made it our business to not do that: ‘We’re quite happy in Southend, for all its faults.’”

While this inward focus might have made it rare for a touring band to pass through the town, Understand did not rest on their laurels. They managed 50 gigs around the country between 1991 and 93 – most of them brief jaunts due to their day jobs. Later, support slots with respected touring bands such as Quicksand and Jawbox meant that Understand were seen by rock journalists as standard-bearers of UK hardcore. But in reality, Understand were a band apart.

“I think there was some latent prejudice,” says Vique Martin, the force behind the Simba fanzine which started in 1992 and spawned a label of the same name. “But I think it came from them not following the politics of the day. They weren’t radically left wing. They were perhaps radically left wing for four Essex lads, but a radically leftwing Essex lad is a rightwing Brighton lad.”

Musically, too, there was a sense of disconnect. “What they were doing didn’t fit in,” she says. “Fabric, Bob Tilton, all of those bands were doing something way more abrasive, noisy or emo. And there were Understand, writing rock songs.”

Said rock songs caught the ear of A&R man Nathan McGough, a veteran of the Factory Records scene who had managed the Happy Mondays. Turning up to see another band at the Sir George Robey in Finsbury Park he encountered Understand and liked what he heard – and saw. “They looked like Backstreet Boys if they were an emo band,” McGough says drily. He was working at East West, then a subsidiary of Atlantic Records that had signed Pantera, the Rembrandts and Missy Elliott. “My only brief was that I had three years, I could sign three bands and one of them had to be successful.”

Understand signed, becoming the only UK hardcore band on a major label while still in their teens and early 20s. “I spent a lot of time going to the label,” says singer Dominic Anderson. “I was trying to understand how it was going to work and to make sure we were doing our part. Ultimately, we were just kids who wanted to be in a band.”

Coleman agrees, but notes that the band were uncertain of the step they were taking. “We discussed whether we were genuinely good enough and ready for it,” he says. “But we also knew how fickle the industry is and that while we might have been better in a year’s time, the offer wasn’t going to be on the table. It was now or never.”

As US label executives hunted for the next Green Day, bands trading DIY ideals for major-label cash spurred an ideological battle. Understand’s decision raised eyebrows in a small community where no UK band had made the leap. “We definitely suffered a backlash,” says Anderson. “I’m sure there were a whole bunch of people who decided they didn’t like the band any more. It’s something we struggled with when we were making the decision to sign.” A very Essex smoke-’em-if-you’ve-got-’em practicality won out. “Nobody became millionaires but it was enough money that we could give up our jobs and focus on the band full-time,” says Anderson.

Nevertheless, it caused ruptures. “Understand didn’t talk to me for two years because I said they were just using the hardcore scene as a stepping stone,” says Martin.

Inevitably, the thunking riffs and jagged edges of the band’s 1995 major label debut, Burning Bushes and Burning Bridges, did little to enrich East West. While McGough suggests the record sold poorly and helped seal his fate with the label, Anderson queries how many copies even made their way into shops. “It’s got to be the most limited-edition major label release in the history of the world,” he says.

Understand were never dropped – their extension option simply lapsed. The group fizzled out in 1999 as other label promises fell through and members prioritised paying the rent, leaving their second album on the shelf. Over the years, they had thought about working up their post-East West demos until they were happy, but time and the unrealistic prospect of a reunion meant that real life got in the way. Then lockdown hit.

“Covid created a work void for me which I was filling with chatting to the boys on WhatsApp and making inane spreadsheets documenting every show we ever played,” says Anderson. “Finally getting our music up to a point where we felt happy releasing it was the natural ending to that.”

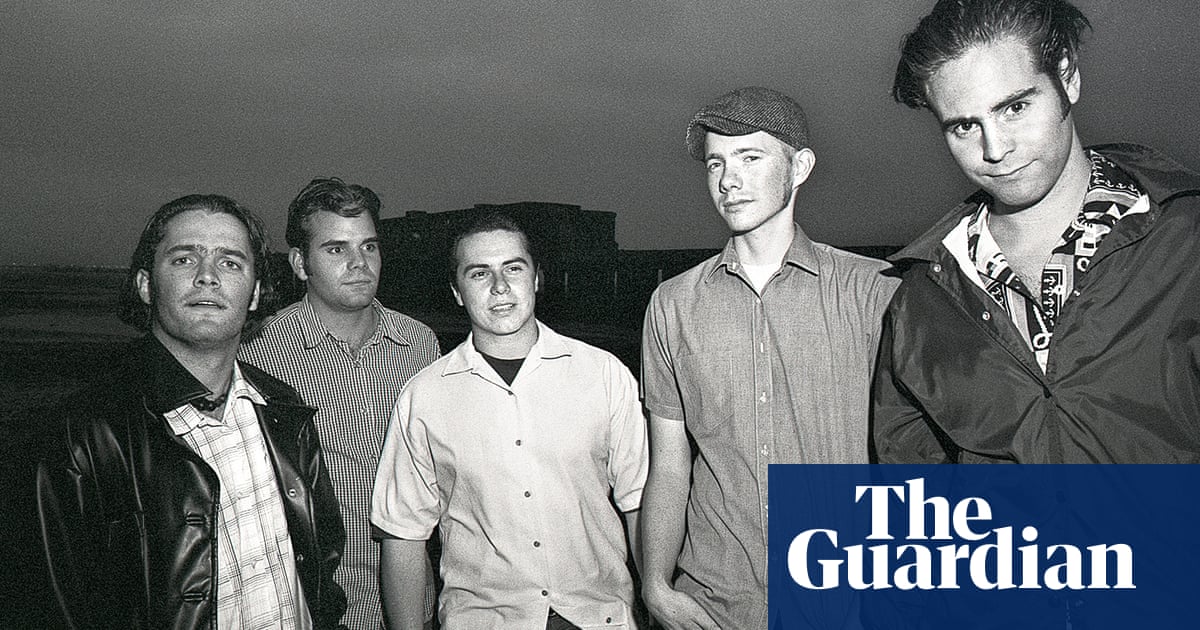

Real Food at Last still crackles with urgency, but has taken on an added poignancy given that guitarist John Hannon unexpectedly died of a heart attack in May 2021. “John passing away during that process was certainly inspiration to see it through,” says Anderson.

Hannon’s post-Understand life had seen him forge a successful career as a respected recording engineer, as well as being a member of the experimental Liberez. “It wasn’t the type of music he was listening to or playing any more,” says Anderson. “But he always found the time and energy to get the digital transfers done, work on remixing and get it ready to send on. As the studio guy he was the keeper of all the tapes and files and the banter we had those days over our group chat was something we have to remember him by.”

As for reunion gigs, “never say never”, says Anderson, while acknowledging that the loss of Hannon – and the band member’s far-flung locations – make it unlikely. Hannon wasn’t the only member of Understand to pursue a career in music. Anderson tour manages Muse and Coleman is Iron Maiden’s lighting designer, while bassist Stuart Quinnell is now a backline tech – currently on the road with singer-songwriter Maisie Peters as she supports Ed Sheeran. Drummer Andrew Shepherd, meanwhile, relocated to Australia and works in photography and video production.

“Everyone came out of Understand self-employed,” says Coleman. “It’s maybe one of the reasons we didn’t carry on, because some of the requirements you get from being in a band are being met elsewhere. There wasn’t the pressure to be in a band when you’re visiting other countries and doing something you enjoy on your own terms. It’s not like I went to work in an estate agents and looked out the window every day wishing I was somewhere else.”

Real Food at Last is released via Rise Records on 7 April.