Aminiature billboard pokes up above the neatly trimmed hedge in the garden of the Schindler House in Los Angeles, as if a roadside ad had blown in from nearby Sunset Strip. Cantilevered from a chunky steel column, strapped to a base of pink concrete blocks, it is a startling arrival on the grounds of this hallowed modernist sanctuary. It’s particularly strange as the hoarding in question is not advertising injury law or a Hollywood movie about a coked-up bear, but a 1970s public housing project in the Mexican city of Guadalajara.

“The billboards are trying to make trouble,” says Mimi Zeiger, co-curator of an exhibition here about the work of Mexican-Austrian architect Alejandro Zohn. She gestures to a range of hoarding structures scattered around the garden of the famous house, like fragments of a more brash urban realm impinging on the quiet oasis, each displaying an image of Zohn’s work. “It’s a way to bring the scale of the city into the more secluded, domestic space, creating a bridge between Guadalajara and LA.”

The bold signs are a provocative addition to the West Hollywood sanctum built by Austrian émigré architect Rudolph Schindler in 1922 and often regarded as the Ur-monument of southern California modernism. The house was designed after Schindler and his wife spent the summer in a cabin in Yosemite national park, and it embodies his desire to channel the sense of camping out in nature in the form of a bohemian shack.

For all the sanctity heaped on it since, the house is a refreshingly rough and ready thing, built on a shoestring. A poured concrete slab serves as both the foundation and finished floor surface, on which the walls were cast flat then hauled up into place, topped with a simple redwood roof, with big canvas panels that slide open to the garden. It is a poetically primitive place, exuding the excitement of outdoor living from someone freshly arrived from colder climes – complete with “sleeping baskets” on the roof (on the assumption that LA was warm enough to spend nights outside. They soon found it wasn’t.)

Since the 1990s, the house has been home to the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, an outpost of the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, hosting a programme that explores the intersection of the two disciplines, while always being careful not to screw anything into the precious walls (the property is owned and maintained by local non-profit, Friends of the Schindler House). It is a fine balancing act of keeping the house sparse enough for the pilgrims who come to worship the purity of the architecture, while injecting enough variety to keep local audiences coming back.

The choice of Zohn is an inspired one. Like Schindler, he was a Jewish émigré to the Americas – his parents fled Vienna in 1939 when he was eight – and a prolific architect, with around 500 projects to his name, yet he remains virtually unknown outside Mexico. Unlike Luis Barragán or Félix Candela, icons of mid-century modernism whose photogenic work travelled widely, Zohn was a generation later (he died in 2000), and was based in the western city of Guadalajara – often regarded by Mexico City’s taste-making elite as a provincial place of tequila and mariachi music.

Rather than stage a straight monographic show, Zeiger and co-curator Tony Macarena (the nom de plume of Mexico City-based “design queeratorial duo”, Lorena Canales and Alejandro Olávarri) invited five artists to explore a selection of Zohn’s buildings through photography and video. The intention was to move away from the documentary mode of architectural photography towards a more subjective position, using the artists’ “acts of investigation and translation” to “find glimpses of [Zohn’s] utopian desire amid the chaos, beauty and violence of everyday life”, as the curators put it. The result is a range of tantalising vignettes that leave you wanting to find out more.

One artist duo, by the name of Lake Verea, has installed a series of huge panoramic prints of Zohn’s Mercado Libertad, hung from rails as if fresh from the darkroom. Zohn designed the indoor market complex in 1953 as his thesis project while at university, composing a dramatic roof of 18-metre-wide parabolic concrete shells, held on slender columns above a 30,000 square-metre hall. He intended it to provide “a framework of greater cleanliness, decor and joy,” compared with the previous crowded market, creating a place “without rigidity or mathematical coldness, but [that rather] achieves the natural and spontaneous arrangement that is observed in street markets”. Some of this informal chaos comes through in the large format prints, while wooden maquettes of the roof structure from Zohn’s archive, displayed in a case nearby, will please architects.

In a small room next door, once the nursery, Sonia Madrigal has installed a haunting grid of images of Zohn’s Edificio Mulbar, a shopping mall and multi-storey car park with a graphic concrete diagrid facade, built in 1974. This project comes with a darker story: in 2019 it was the site of the murder of Atzhiri Paulina Sánchez Sánchez, a young woman who had gone up to the ninth floor to photograph the sunset. Madrigal tried to shoot the building last year, but was escorted from the site by security guards, forcing her to document the structure in other ways – including in an eerie shot from her hotel room across the street. “With this action,” she says, “I try to evoke the many rights – to access and safety – that continue to be denied to women.” On the opposite wall hangs a charged pastel sunset, shot from the ninth floor.

Cheerier scenes of the colourful lives framed by Zohn’s buildings come in the form of Onnis Luque’s images of the CTM-Atemajac collective housing project, designed as a complex of 470 homes with balconies looking on to sociable courtyards. Built in 1979 as housing for transport workers, Luque’s vivid documentary images show how residents have adapted and appropriated Zohn’s bricky armature over the years, from installing religious altars to adding makeshift washing lines, along with layers of graffiti and planting.

A more gnomic contribution comes from Adam Wiseman, whose video installation of Zohn’s acoustic concrete bandshell, built in 1958 in Parque Agua Azul, is projected alongside photographs of trees that have been marked with mystery daubs of red paint. The video contrasts footage of a solitary figure practising the yo-yo with an energetic concert by rock band El Tri, performed on the very same stage, suggesting Zohn’s parabolic canopy is a democratic shell for everyone.

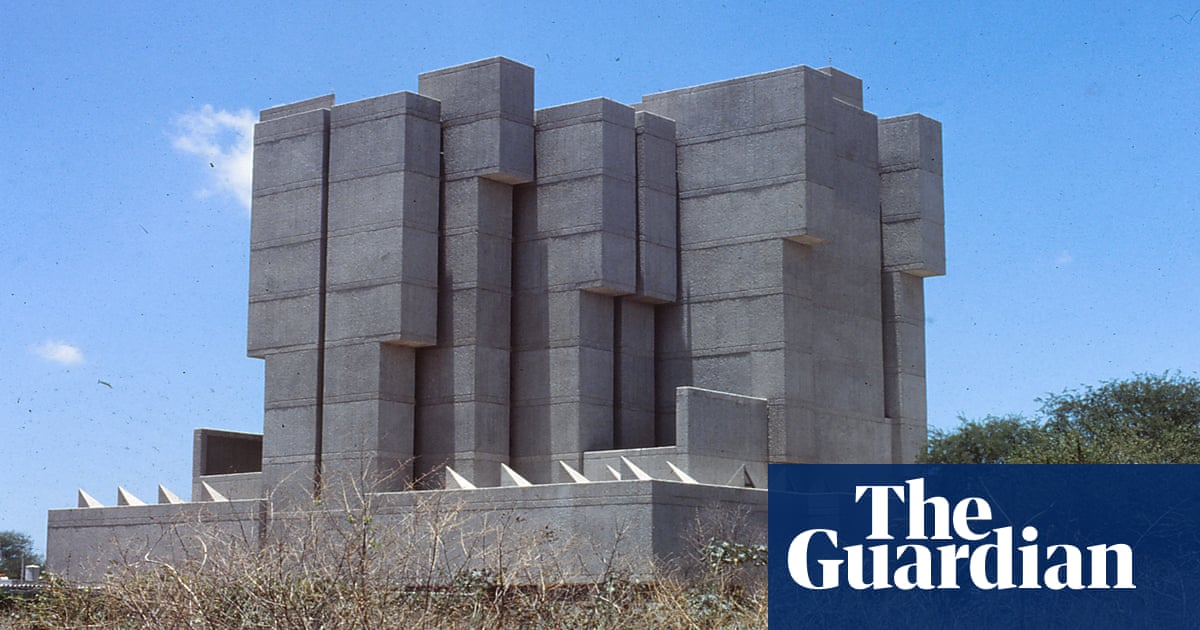

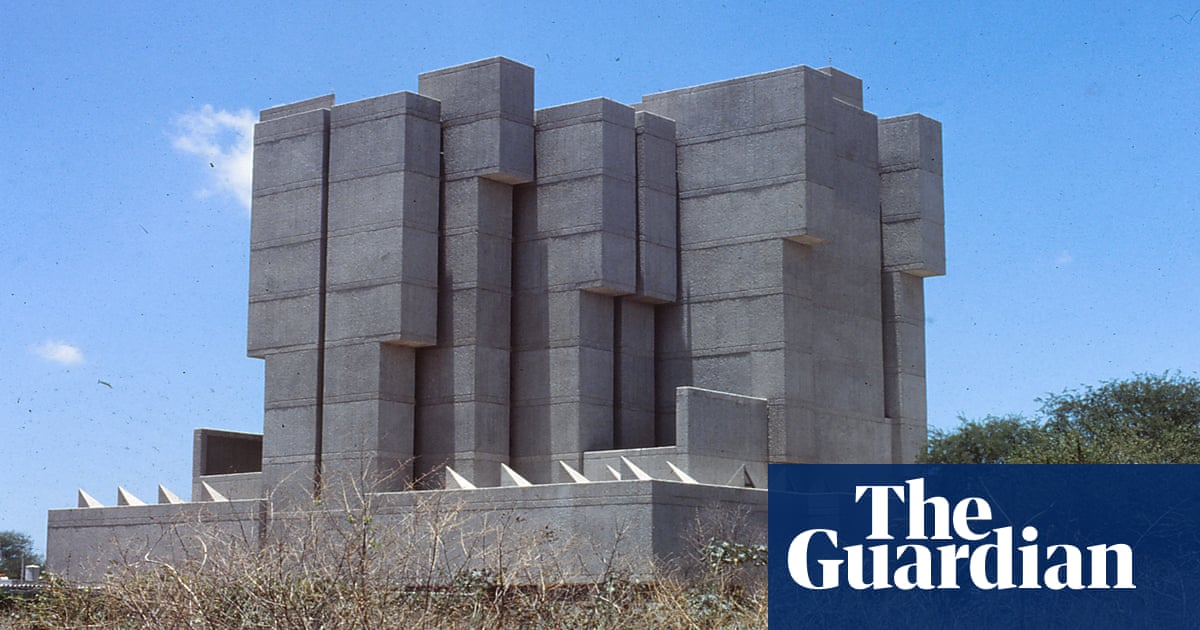

A final room is dedicated to photographs of Zohn’s state archive building, a castle-like cluster of cubic blocks, hammered with vertical lines to create the finest corduroy concrete.

Almost everyone in Guadalajara has been to El Archivo – a visit is required for registering births, marriages and deaths, as well as securing building permits. As photographer Zara Pfeifer puts it, “each cycle of life is intertwined with the structure”. Her images reveal a more humane side to the fortified bastion, showing its courtyard alive with citizens waiting patiently for the wheels of Mexican bureaucracy to grind into action, while street vendors ply their trade in the welcome shade of the big blocks.

The photographic work offers alluring glimpses of the multiple facets of Zohn’s many backdrops for life, but perhaps the most tangible evidence of his sensibility can be found in the contribution of a contemporary Guadalajara-based designer. Moving from Mexico City during the pandemic, Fabien Cappello became fascinated by Guadalajara’s network of hojalata workshops that make everyday functional objects from tin-plated or galvanised steel, such as watering cans and buckets. He collaborated with a number of these craftspeople to produce a range of stools, lampshades, candlesticks, bowls and watering cans, each cut, bent, crimped and soldered by hand. Dotted around the minimal interior of the house, they inject a down-to-earth, ad hoc spirit that seems to unify the loose-fit attitudes of Schindler and Zohn. Pleasingly at odds with the museum’s “do not sit on the furniture” signs, they provide welcome places to perch.

Seeking Zohn is at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, West Hollywood, until 23 July.