Joe Biden has, since the 1980s, pushed for greater US involvement in Irish affairs. However, his big presidential visit this week will probably not decisively break the latest post-Brexit political impasse there.

The trip is a genuine historic occasion, which has drawn some parallels with that of John F. Kennedy some six decades ago. Like Kennedy, Biden is proud of his Irish ancestry. He is the great-great-grandson of emigrants across the Atlantic more than 165 years ago.

However, it is a more recent development that has shaped the visit — the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement that ended the three-decade conflict known as the Troubles, which stemmed from nationalist-republican tensions in Northern Ireland and claimed more than 3,500 lives.

In the quarter of a century since the deal was signed, many in Northern Ireland agree that the province has changed significantly for the better. This is not just because of the increased political stability, but also because of the stronger economic prospects, including the £1.5 billion ($1.8 billion) in US investment in the last decade. The UK government is also planning to host a Northern Ireland Investment Summit in September to try to secure a new wave of long-term capital for the nation.

In the two and a half decades since the Good Friday Agreement, however, Northern Irish politics has been punctuated by crises, including the latest one. The Democratic Unionist Party has boycotted the Stormont legislature since last year, citing its concerns about post-Brexit governance.

In last May’s elections for the assembly, the Irish nationalist Sinn Fein party replaced the DUP as the largest party for the first time, allowing it to choose the first minister. However, Stormont has not sat since then due to the DUP boycott and the London government has warned that it may be forced to reintroduce direct rule if there is no sign of local power-sharing arrangements restarting.

Biden has been encouraged by the latest post-Brexit deal agreed in February between the UK and EU

Andrew Hammond

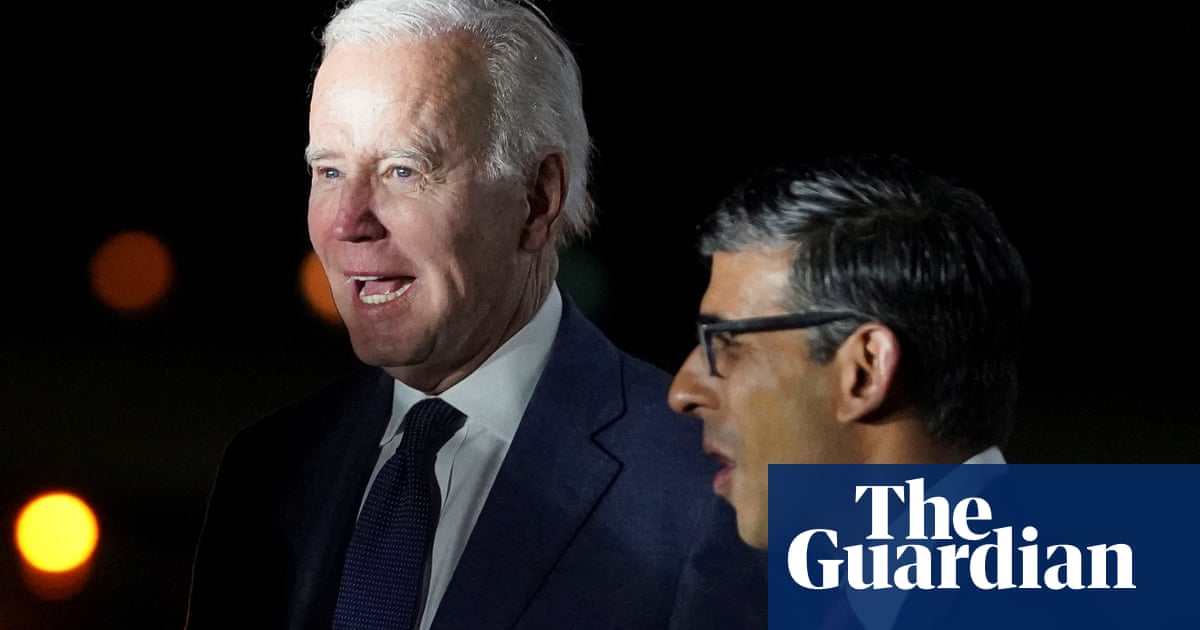

Biden’s Northern Ireland envoy has urged its political parties to adopt “pragmatism” instead of “refighting old conflicts” to encourage a new wave of international investment. The president held talks this week with UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and held a public event with the main Northern Irish parties, including the DUP and Sinn Fein.

Biden has been encouraged by the latest post-Brexit deal agreed in February between the UK and EU, the so-called Windsor Framework. This was unveiled as a means of adapting the post-Brexit Northern Ireland Protocol to deal with trade disruption. The protocol had originally been agreed by former UK premier Boris Johnson as part of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement in December 2020, which formally took the country out of the bloc. Its purpose is to prevent a “hard border” (any kind of physical border or visible customs checks) on the island of Ireland, given that the Republic of Ireland remains in the EU, while Northern Ireland has left along with England, Scotland and Wales.

Biden has praised the Windsor Framework, saying that it is a “vital, vital step to ensure all the people of Northern Ireland have the opportunity to realize their full potential.” However, while the DUP says that the deal has gone some way to addressing its concerns about the nation’s post-Brexit governance, it asserts that significant problems remain and has made clear its boycott will continue until it secures further assurances. The DUP is very sensitive to any post-Brexit arrangement for Northern Ireland that leaves it out of sync with England, Scotland and Wales, given its strong commitment to remaining in the UK.

While the position of the DUP is frustrating politicians across much of the rest of the political spectrum, it is not an entirely new stance for unionists to take. For example, the late Lord Trimble, as an ex-leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and former first minister of Northern Ireland, said in 2018 that any post-Brexit posture that leaves the nation with a special status vis-a-vis the EU would kill the key tenet of the Good Friday Agreement that there would be no constitutional change without majority consent.

Meanwhile, the DUP is supported by some Conservative MPs, including Johnson, who voted against Sunak’s accord. Part of the reason for this is that some of these politicians assert that allowing Northern Ireland to be treated differently from the rest of the UK could be a political fillip for the Scottish National Party administration in Edinburgh and others in England and Wales who want to see the country rejoin the EU, including the single market and customs union.

Taken together, this is why a big breakthrough in Northern Ireland’s latest political impasse will be difficult to achieve. While the US president’s visit has been widely welcomed, the issues involved in the DUP’s boycott will probably not be fully unraveled this week.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.