Following William Burns’ visit to Saudi Arabia this month, one has to wonder if the US is aware of the state of Middle Eastern affairs beyond its own lens. During his visit, the CIA director reportedly told Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that the US felt “blindsided” by Riyadh’s rapprochement with Iran and Syria — Washington’s regional rivals. These remarks can be interpreted as quite ironic, given Burns’ role in the Obama administration and its shaping of the new US policy toward Iran, correcting the neoconservative policies that led to Washington making mistakes in Iraq (since 2003) and Afghanistan (2001-2021).

In 2009, Burns explained that, in recognizing that Iran is a significant regional player, “our basic goal should be to seek a long-term basis for coexisting with Iranian influence while limiting Iranian excesses; to change Iran’s behavior but not its regime.” This policy approach advocated by Burns 14 years ago is very close to the Saudi approach to Iran in 2023. The only difference is that the US was genuinely naive about its ability to change Iranian behavior through a policy of engagement without any external constraints. Today, the Saudi approach toward Iran assumes that China’s influence on Iran’s decision-making process is strong enough to open the ground for a policy of engagement. Nevertheless, the Saudi approach is not solely based on the hope that engagement will be sufficient to alter Iran’s nuclear, military and regional policies.

Successive Democratic and Republican administrations have dented US credibility in the Middle East because of their frequent chopping and changing of policies toward Iran. The economic cost of the Ukrainian war, failure to resolve the Palestinian issue, support for the so-called Arab Spring and domestic polarization have further dented US credibility among regional countries. In comparison, one has to consider the Chinese investments in different countries that have paved the way for Beijing to shift from soft power to geoeconomics and geopolitics.

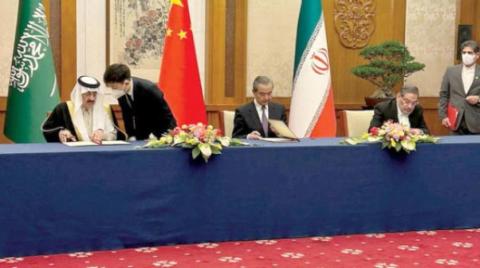

China’s rise in the Middle East has to be understood through the lens of Beijing’s economic partnerships with all regional countries. This economic approach is very different from the US policy of projecting military power against weak regional adversaries, such as the Taliban in 2001 and the Saddam Hussein regime in 2003. As Robert F. Kennedy Jr. explained on Twitter: “China has displaced the American Empire by deftly projecting, instead, economic power. Over the past decade, our country has spent trillions bombing roads, ports, bridges, and airports. China spent the equivalent building the same across the developing world.”

The US was genuinely naive about its ability to change Iranian behavior through a policy of engagement without any external constraints

Dr. Mohammed Al-Sulami

Moreover, since the Obama era (2009-2017), the reactive dimension of US policy in the Middle East has provoked confusion among Washington’s regional partners. The lack of US support for its regional allies during the so-called Arab Spring and the idea of rapprochement with Tehran at a time of social turmoil in the region pushed the majority of its Gulf allies to seek a new foreign policy based on autonomy and diversification. Both the neoconservative failure to change the region through wars and the Democratic approach of promoting US influence while not prioritizing its allies and partners in the region have been factors accelerating its regional decline.

Moreover, Barack Obama’s regional policy based on a critical view of Gulf states, as well as the regional wars under the neocon-backed George W. Bush administration, led to a US credibility gap in the Middle East. Beyond the warmongering and a sense of American moral superiority, one has to consider the devastating impact of US internal debates on the country’s prestige worldwide, especially in the Middle East.

Since the Obama policy review on Iran, there has not been any consensus between Washington and its regional allies on Iranian issues. Thus, in the region, there is now a fear that the Democrats’ regional policy will be determined by their desire to do the opposite of what Donald Trump did. In this US domestic context, the positive atmosphere of Saudi-US relations under the Trump administration turned colder and more tense at the beginning of the Biden administration.

This partisanship reinforces the regional perception that America’s Middle East policy reflects domestic polarization more than any real desire to address regional issues and concerns. This US-centric approach is no longer acceptable for the region’s countries. On the contrary, given past US mistakes in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Biden administration should seek advice and insights from its regional partners to improve US influence and regain some of the prestige lost since the neoconservative wars.

It therefore seems more essential than ever for Iranian hawks and Democratic doves to emerge from their sterile internal debates to devise a new regional policy that is in line with the region’s sociocultural transformation. It should favor political stability and an economic win-win approach, rather than the short-term internal interests of political factions in Washington. If not, China’s rise will continue in terms of both geopolitics and soft power.

Dr. Mohammed Al-Sulami is president of the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah). Twitter: @mohalsulami