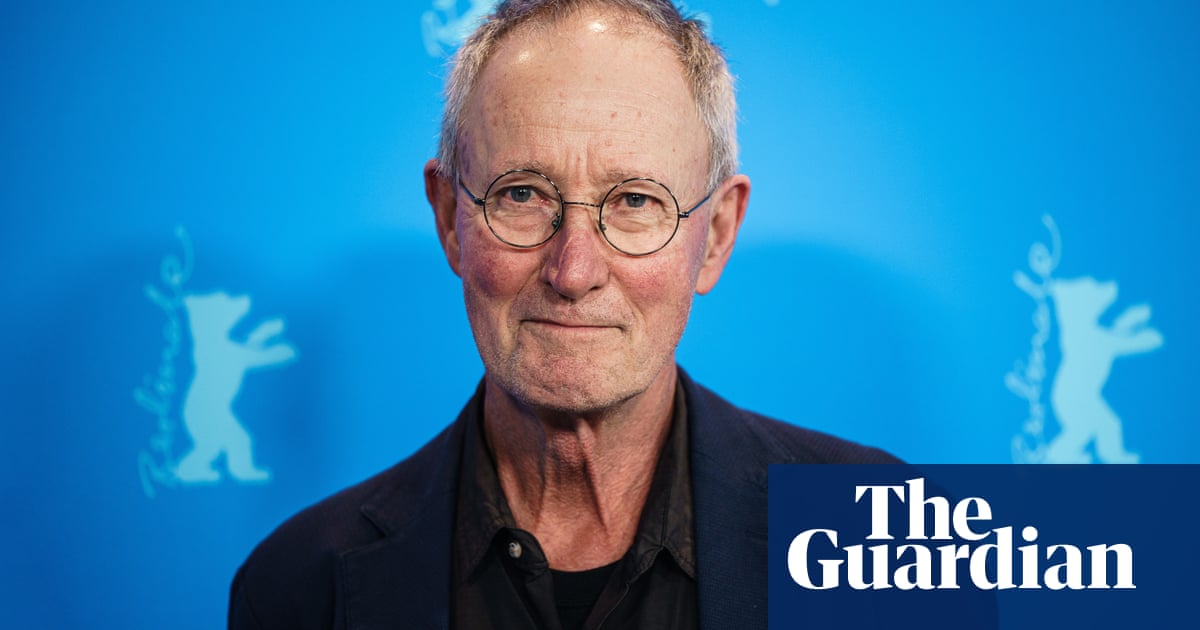

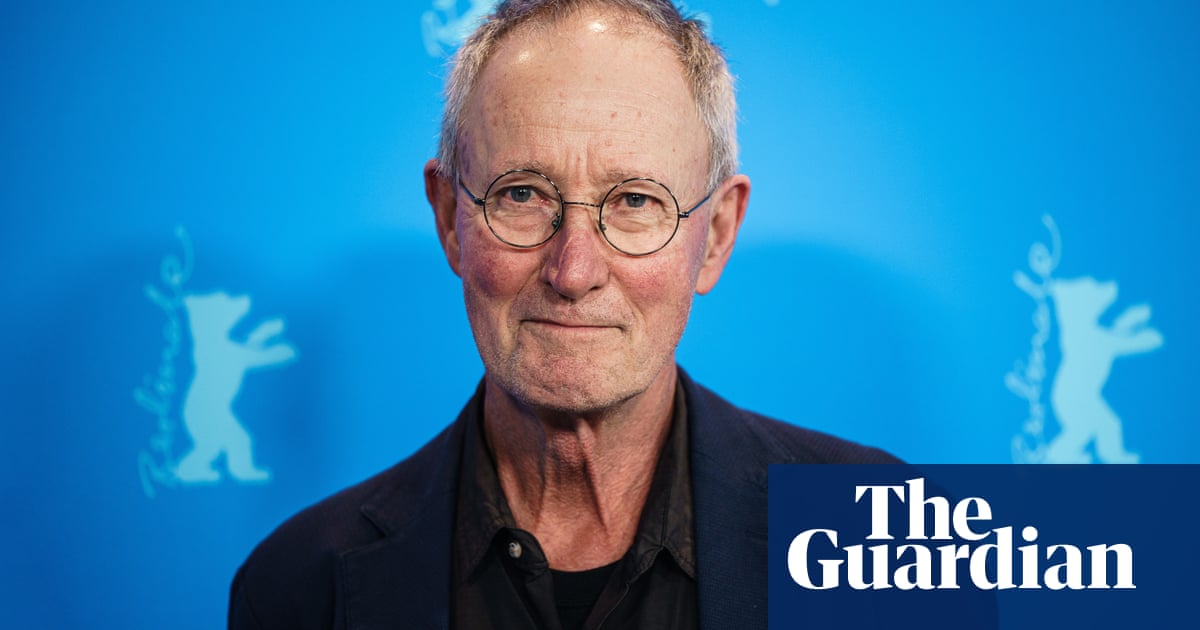

It has been almost a decade since Rolf de Heer’s last film, but the Dutch-Australian director has returned to the big screen with a renewed sense of urgency. The Survival of Kindness, a dystopian journey through hinterlands and cityscapes disfigured by a catastrophic event (probably plague) shows that the 71-year-old film-maker’s narrative powers are undiminished: the film won the top jury prize at this year’s Berlin international film festival.

Set against the beautiful backdrops of Australian desert and mountain wilderness, foregrounding brutality and compassion in a post-apocalyptic world, there is, as with each of his films, a surprise nestled within The Survival of Kindness: the absence of any intelligible dialogue. It is a risky choice. Yet creative risk, in one form or another, has consistently characterised all of de Heer’s films.

There is Bad Boy Bubby, the controversial black comedy that propelled de Heer to fame, and a certain notoriety, 30 years ago. Or the intimate family dramas like The Quiet Room, with its mute child protagonist; or Dance Me to My Song, where de Heer cast a lead actor with cerebral palsy, who was unable to walk or could only speak with a voice synthesiser. Or his unwillingness to depict the violence of Australia’s brutal frontier wars in The Tracker, where he used still images of paintings to represent events instead. Or Ten Canoes, the first full-length Australian feature made entirely in Indigenous language, which received widespread critical and popular acclaim.

His remarkable new film, The Survival of Kindness, is his first since 2014’s Charlie’s Country, which starred his friend and collaborator David Gulpilil, who won best actor at Cannes for his performance and died in 2021, after a long illness. Over the new film looms a big question: what drew de Heer back to cinema, after a decade away?

“I was needing to make a film for complex reasons, including needing to learn how to make a film differently because everything had fallen in a heap, really, for cinema,” de Heer says.

Sign up for our rundown of must-reads, pop culture and tips for the weekend, every Saturday morning

When Covid-19 arrived, it brought into focus all manner of intransigent social justice issues, in particular access to healthcare during Covid, and the Black Lives Matter movement. It also made him wonder: could you still make cinema when all the cinemas were shut?

“I wasn’t looking for anything specific. I wasn’t looking for Black Lives Matter stuff. It’s not something I intended to do but when it started to go in that direction, I simply allowed it to,” he says.

His willingness to be guided by his instincts has defined de Heer’s career; often his films are made because an incident has energised him, or a moral imperative has prompted indignation. As a result, his work is characterised by its concern for the subjugated and the vulnerable, and The Survival of Kindness is no different: following a character only known as BlackWoman (played by Mwajemi Hussein) on a lonely journey across a brutal land. She escapes enslavement in early scenes that reveal the depths of depravity of her white captors, and finds herself free in an apocalypse, where cruelty is rampant and man’s inhumanity to man is everywhere – except among people of colour.

Hussein, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo who has now settled in Australia, had never been inside a cinema before she auditioned for the lead role – and yet, she carries the film with her nuanced and moving performance. “It’s not a coincidence that somebody correct for the casting is more likely to be a refugee in this country than somebody who’s not,” de Heer says.

BlackWoman is fundamentally kind and compassionate, but it is apparent, as she mischievously switches costumes on figures in a colonial museum, that life has not entirely robbed her of humour – or that it has bestowed on her infinite patience either. She’s no Mother Teresa, is she? “She may be, because Mother Teresa was apparently quite short-tempered!” de Heer laughs.

De Heer “started off not thinking at all about the content and … spent the best part of a couple of weeks thinking about locations”. The hunt began near his home in the far south of Tasmania, which he and his partner, fellow film-maker Molly Reynolds, built together. From there, de Heer would drive to kunanyi/Mount Wellington to walk the trails. It was there that a particularly vivid image sprang to mind: his friend and Ten Canoes co-director Peter Djigirr locked in a cage on a trailer abandoned in the desert. This would become The Survival of Kindness’s shocking seminal image, except that it is BlackWoman locked behind bars.

De Heer then set off for the Flinders Ranges to scout for more locations. During lockdown, when cinemas were closed and audiences were streaming in their homes, he was looking for places that would bring them back to the cinema.

“A lot of it was to do with thinking about cinema. All I could do was try to make something very cinematic,” he says. “I spent a lot of time on my own, living in the world of a film that I didn’t yet know.”

The actors speak in combinations of their first and second languages, “using the apparent grammatical structures, and cadences and inflections, but nobody from their language group would ever understand because it was just nonsense,” says de Heer, who was “quite taken by that feeling of having to communicate things visually, with body language, and with sound.”

De Heer’s pragmatic side, which has stood him so well over decades of low-budget indie productions, saw him develop a nimble production strategy: a skeleton crew shooting in outdoor locations, which was already his preferred modus operandi. But he also substituted his usual crew for a much younger, culturally diverse and gender-balanced crew, which felt consistent with a film that foregrounded social injustice and racial oppression.

“Once the project required financing, I decided that it made no sense to go running around the countryside with the same crew of old, middle-class, you know, codgers,” de Heer says. “It just didn’t make sense. What does make sense is to just go radical, go the whole way. We got heads of department who, what they lack in experience they make up for in passion.”

The result, he says, “felt good to everybody”; he had reassured himself that “if there’s any film that you make where you can do this, it’s this one”. There was no need to record dialogue on location; the locations were “already cinematic, so you didn’t need a big art department”.

Lockdown restrictions are now lifted and the film-maker considered by many to be Australia’s leading auteur has released one of his most confronting works yet. Typically, his films, however grim, have found a way to conclude with a little uplift. But audiences will be left with something else at the end of The Survival of Kindness, which was an easy decision for de Heer to make.

“I think I found the ending fairly early in the process. It released me to do more in the guts of it. With BLM happening …” – a thoughtful pause – “how long is this going to take?”

The Survival of Kindness is out in Australian cinemas from 4 May. Jane Freebury is the author of Dancing to His Song: The Singular Cinema of Rolf de Heer