On the morning of 9 April 1968, some 1,300 mourners crammed into Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist church for the funeral of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. At the end of the pew, two rows behind the King’s grieving wife and survivors sat a man in a trim black suit and sunglasses gazing longingly at the casket before the pulpit, like a boat set adrift. That was Harry Belafonte, always in frame any time the civil rights struggle was in focus.

On Tuesday, more than a half century after King was killed by an assassin’s bullet, Belafonte joined his close friend and confidant on the other side of the ancestral plane, dying of congestive heart failure at the age of 96. For as much of an impact he made as an actor and musician, it’s Belafonte’s legacy as an activist that towers like a eighth wonder monument over the current era of lapel-wearing, hashtag virtue signaling. Time and again, when Belafonte rightly could have looked out for No 1, he cannonballed into every social justice movement, protesting against apartheid, pushing for LGBTQ+ equality and condemning the military industrial complex.

Even as the decades advanced, he never seemed to tire of the fight. “The reason that I hang around is to make sure, in my old age, if I live to see it, that I’ll be able to say that in my lifetime I did all that I could with what was at my disposal,” Belafonte said in a 1967 CBC interview. “Because I would hate for my children to look at me and to say, ‘Where were you during the moment of the great decision?’”

Where Muhammad Ali styled his celebrity into a civil rights case, Belafonte was a grassroots organizer who happened to be one of the most consequential and enduring entertainers on the planet. And Belafonte’s unwavering passion for the cause and unwavering commitment to see the mission through could put him at odds with celebrity influencers who preferred to take a more subtle approach. But even as he publicly sparred with Jay-Z and King’s children, Belafonte remained an immovable presence on the protest frontlines, stumping for the Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements. In 2013, at age 86, he made a shock cameo at a student sit-in outside the Florida statehouse office of the then governor, Rick Scott, after Trayvon Martin’s killing. “I’m just here to support these people and to tell [Scott] that if he’s at all in touch with history, he should know that this is just the beginning of the journey,” Belafonte said.

Belafonte’s rebel spirit came from a youth weathered under heel. Coming of age in the 1930s between his native Harlem and his parents’ homeland of Jamaica, Belafonte became attuned to both the American and British flavors of racial subjugation. He enlisted with the US navy during the second world war to defeat fascism, only to return home a villain to the same white Americans who decried the Nazis. So it figured he’d model himself after Paul Robeson – the great baritone who was called crazy, un-American and blacklisted for speaking out against segregation. “I was an activist who became an artist,” Belafonte told PBS in 2011. “I saw theater as a social force, as a political force.”

Eventually, Belafonte, too, landed in the US government’s bad books. His budding career would probably have suffered the same fate as that of his idol if Ed Sullivan hadn’t defied the blacklist and invited Belafonte on to his late-night TV show in 1953. And yet even as he was accorded this lucky break, Belafonte couldn’t just shut up and sing. When Sullivan questioned Belafonte’s politics, the singer equated the Black struggle to the Irish struggle against the British. Sullivan, a descendant of the Emerald Isle, had Belafonte on nine times more after that.

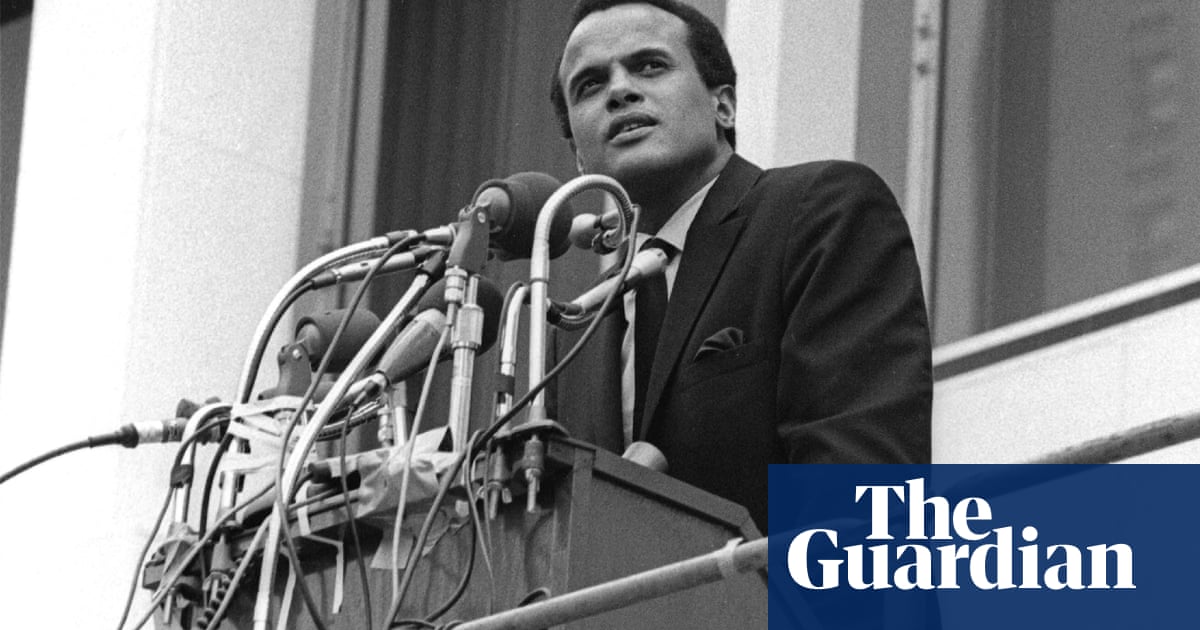

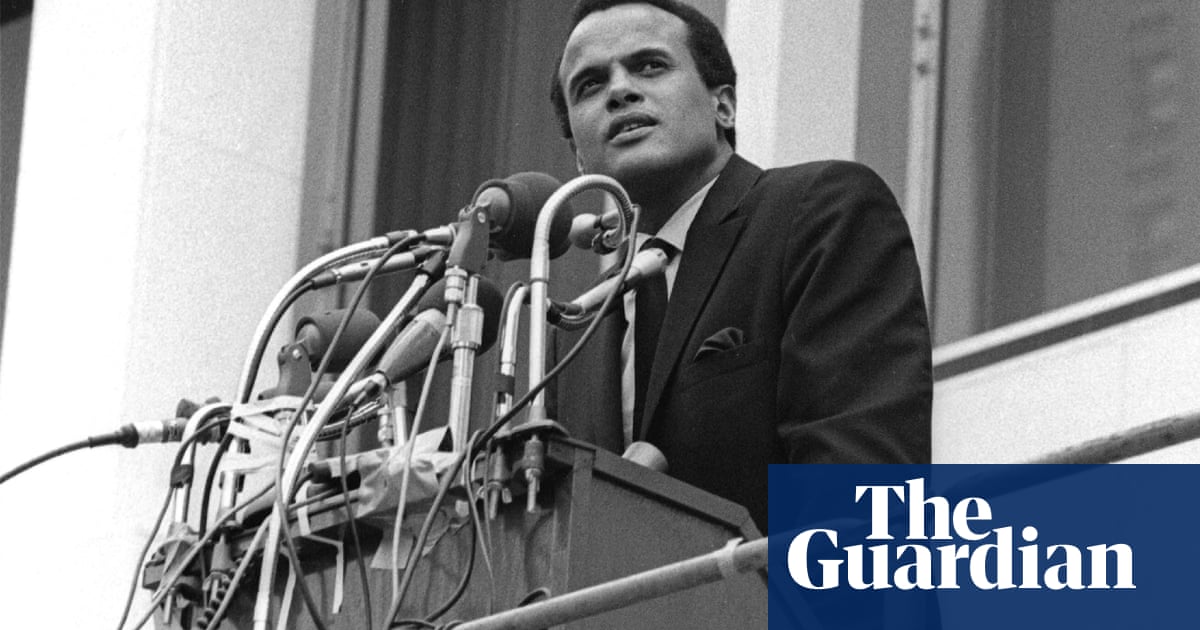

Such was the undeniable effect of Belafonte, as talented and winsome as he was quick-witted and eloquent with that trademark rasp of his. At the March on Washington on 28 August 1963, Belafonte popped up again on the National Mall not long before King delivered his seminal I Have a Dream speech. “Artists have a valuable function in any society since it is the artist who reveals the society to itself,” Belafonte intoned. He rarely showed up in the civil rights fight without backup. “Harry wanted very much for Dr King to understand there were people in Hollywood who really cared,” Egot-winner Rita Moreno wrote in Variety, recalling the star-studded delegation Belafonte took to Washington. “There’s a great photograph of myself, Marlon Brando, Harry and James Garner posing on the steps of the plane.”

Belafonte recruited good friend Tony Bennett to lock arms with him and others for the third march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on 21 March 1965, an event he even had a hand in orchestrating. Belafonte was a major financial backer of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, his initial $40,000 contribution helping to launch the organization’s peaceful protest work in the rural south. “Whatever money I had saved went for bonds and bail and rent, money for guys to get in their car and go wherever,” he told the New York Times in 2017. “I was Daddy Warbucks.”

In 1968, in the midst of the raging civil rights protests, Belafonte sat in for Johnny Carson at NBC’s Tonight Show desk, the first Black person to host the late-night institution. Somehow, he convinced the network to book his great friend, AKA the FBI’s No 1 public enemy, as a guest.

King settled right in, unbuttoning his black suit jacket, flashing a bright smile and appearing more at ease than most white Americans had ever seen him. King started out with an anecdote about how lucky he was to be sitting with Belafonte in Los Angeles after suffering through mechanical issues on his flight out from Washington. “I don’t want to give you the impression that as a Baptist preacher I don’t have faith in God in the air. It’s simply that I’ve had more experience with him on the ground,” he said to roaring laughter. Two months later he was dead.

Belafonte is the rare prominent civil rights activist who was lucky enough to survive the raging 60s. For many, that would have been accomplishment enough. But Belafonte kept pressing on with the fight, kept reappearing in “the moment of the great decision” to interject. It’s a depth of commitment and intensity of conviction that won’t soon, if ever, be matched. As King put it to Belafonte on the Tonight Show: “It represents a real and genuine courage.”