Isaac Julien presents 11 films at Tate Britain with a combined running time so voluminous you might want to make a day of it, with respite for lunch. They include a group of early works from the 1980s, screened on monitors and walls outside the exhibition, and seven multiscreen films in darkened theatres within. Copious seating, sumptuous carpets, ideal viewing ratios, barcodes that let you watch again later back home: everything has been arranged for your comfort.

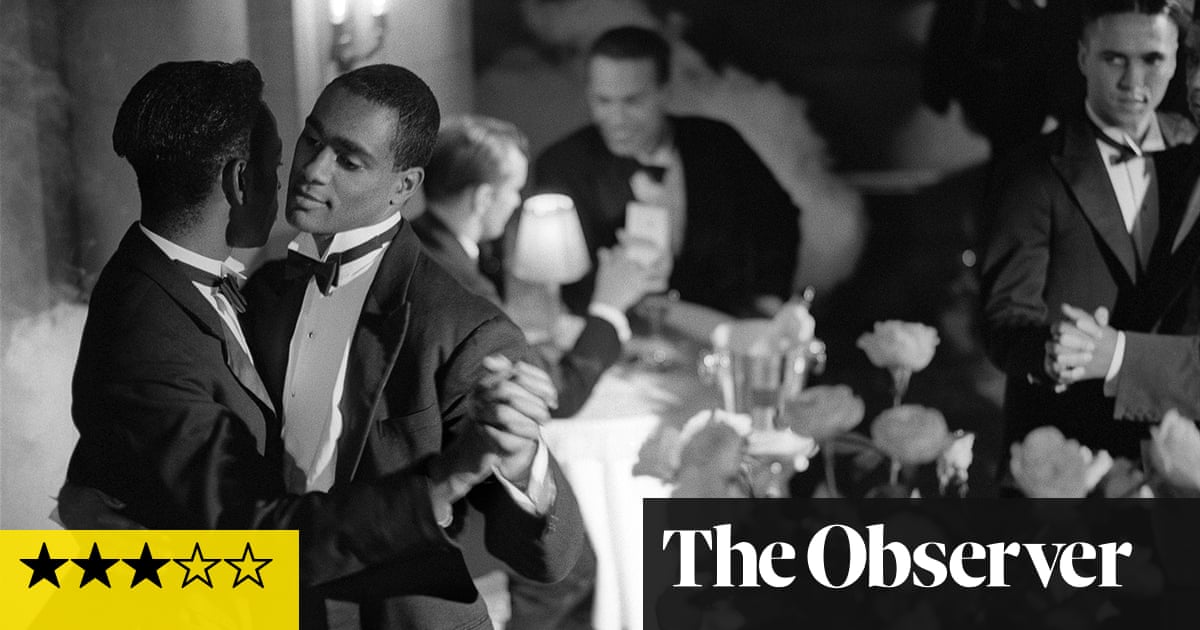

Which is worth bearing in mind as you witness the works of this inveterate seducer. Born in 1960, and starting out with experimental documentaries about police brutality, black life and culture in London, Julien found fame early on with Looking for Langston (1989). What he calls a “meditation” on the ambiguously queer identity of the black US poet Langston Hughes set out the elements of his style: fact interspersed with fiction, documentary with drama, drifting dreamscapes with archive footage, montages of dance, song and monologue, the camera hovering on beautiful people and places.

Acclaimed as the first art film made about the historical condition of being both black and gay, this cult work glitters on continuous loop at the heart of the show, and if you start here something particular starts to emerge. The film opens with an imaginary vision of Hughes’s funeral, the deceased played by Julien himself, motionless against white drapes in a coffin. This is an art of commemoration.

Here is A Marvellous Entanglement (2019), honouring the wild architecture of the Italian modernist Lina Bo Bardi, filmed across seven public buildings she designed for Brazil. Some are still in use, with their cave-mouth doors and windows and their curious cylinders of light. Others are derelict, and haunted by the spirit of the architect herself, played by two different women.

They wander through her art museum, where the paintings project from resin bases like gravestones in a cemetery, down spiralling staircases, followed by dancers in descending flurries, through Bo Bardi’s São Paulo theatre with its bare wooden seats. They give utterance to her strong opinions (against upholstery, in favour of mud), in particular her idea that time is not linear but “a marvellous entanglement, where at any moment, points can be chosen and solutions invented, without beginning or end”. Which might stand as the definition of Julien’s own free-flowing films, which so studiously avoid mounting into narrative.

There are other wraiths. A Regency dandy dances through the convoluted spaces of Sir John Soane’s Museum, apparently observed only by a black curator (the voiceover is in Creole, as if Julien did not want you to comprehend). A famous performance by one of China’s great silent movie stars, Ruan Lingyu, is reprised by the contemporary actor Zhao Tao in the streets of old Shanghai. The abolitionist and freedom fighter Frederick Douglass, played by Ray Fearon, gives a visionary lecture to an audience of Edinburgh Victorians, two of whom are moved to make their own protest in crinolines, while his second wife sits stitching a blue coat for him and his (abandoned) first wife sits pensively for a daguerreotype: the shadow of her existence caught on camera. That coat is cobalt, like his first wife’s dress. A dancer whirls in flaring scarlet.

The Chinese movie turns from monochrome into magenta, cerise, cerulean and lime. Julien’s high interest in colour extends to the aspect of every single thing in every scene. His camera dwells on shimmering makeup, coiffed hair, buttons, stitches and velvet, on honed bodies and chiselled faces, bentwood furniture and the breeze lifting a gauzy blind. It slips in and out of The World of Interiors.

Hot colours, languid imagery, the focus on showy details, all of it converges with the smooth movement of each film – gliding gradually through buildings, forests and cities, on trams, trains and slow boats. Occasionally, as in Ten Thousand Waves, partly shot on location in Shanghai Film Studios, it pans back to show the camera crews at work. This acknowledgment of the means of making goes straight to Julien’s modus operandi: glossy, luxurious, swanky aesthetics made to carry a burden of theory.

The latest work here is Once Again… (Statues Never Die), from 2022, commissioned and filmed at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. André Holland (of Moonlight fame) plays the black philosopher and theorist Alain Locke, who was unmistakably gay, and pursued the young Langston Hughes. Locke appears in dialogue with Albert Barnes (played by Danny Huston), debating the status of the African art Barnes bought for his collection in the 1920s, which “is in danger of becoming a fashion or fad”.

Their conversation is intercut with footage from You Hide Me, a 1970 film shot by Ghanaian artist Nii Kwate Owoo in the British Museum stores arguing for the repatriation of the Benin bronzes. There are fragments of a 1953 Chris Marker film, extracts from Looking for Langston and a subplot in which Locke falls in love with the black artist Richmond Barthé. It all streams before you in coruscating black and white on five double-sided screens, themselves reflected in mirrors all around the gallery, and with a spectacular score and arias performed by the black singer Alice Smith. But still it remains a lecture swathed in silver-screen glamour.

It is a risk, even in art film, to be so averse to narrative, pace or tension. Form and content sometimes seem so separate and inert in these works as to make you wonder what is even being attempted. Why is there a second actor playing Bo Bardi, when she mainly seems to repeat the first? Why is there such emphasis on the Scottish skies when Douglass pays his Edinburgh visit? Why does Julien suddenly show the Chinese goddess Mazu (Maggie Cheung), fabled for leading fishers to safety, being hauled back and forth in a harness against a green screen? It is the most atrocious bathos.

The more so because this film is a requiem, of sorts, for the 23 Chinese cocklepickers who died in Morecambe Bay in 2004. An emergency phone call is played out over footage of terrifying tides. We hear intensely elegiac lines from the poet Wang Ping. But then we’re straight back to cinematic old Shanghai. This is almost as tendentious as the stylised sequences in Julien’s 2007 Western Union: Small Boats, where dancers were actually choreographed to play immigrants drowning during fatal Mediterranean crossings. There comes a point where Julien’s “political lyricism”, to borrow a phrase from Derek Jarman, gets uncomfortably close to slick mannerism.

Isaac Julien: What Freedom Is to Me is at Tate Britain, London, until 20 August