Majority of Rohingya refugee children in India deprived of any formal education

Kids do not have government-issued identity documents required for school admission

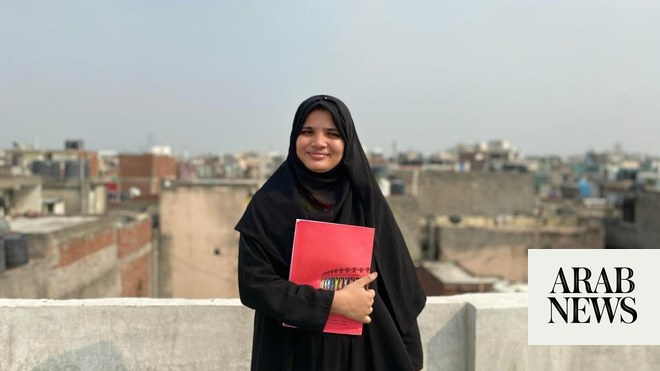

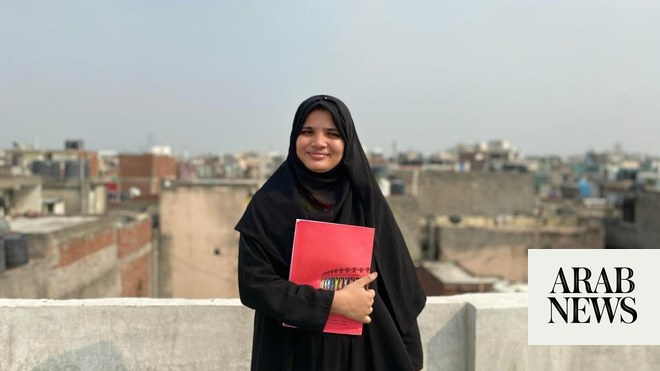

NEW DELHI: In a small Rohingya neighborhood in Jamia Nagar, central Delhi, Tasmida Johar lives like any other girl from the refugee community, but with an achievement only she has managed so far: university graduation.

Johar and her parents lost everything and became refugees in 2005, when she was seven years old. They fled Rakhine State in Myanmar for neighboring Bangladesh, where Rohingya Muslims have for years sought asylum from persecution.

After years in Cox’s Bazar, the world’s largest refugee settlement, the family moved to India in 2012, where they are now a part of a 40,000-member Rohingya community.

“But our struggle did not end. We were not entitled to study in any government schools in the absence of valid Indian documents. I wanted to study in a government school but that did not work out. It was really next to impossible,” Johar told Arab News.

India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, which outlines the rights of refugees and the legal obligations of states to protect them.

It also does not have the relevant domestic laws and the majority of Rohingya children are deprived of any formal education as they do not have government-issued identity documents which in India are required for school admission.

But Johar tried anyway, obtained informal schooling, took correspondence courses, and used all other possible ways to make the impossible happen.

In 2019, after completing high school with the support of the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative of the German government, she secured admission in an online bachelor’s program to study political science at Delhi University. She graduated in December last year, at the age of 25.

“Generally, you finish your graduation by the age of 21, but in my case, it took four extra years because of the periodic displacement and uncertainties,” Johar said.

“It feels nice that I became the first woman from my community to graduate. But at the same time, it makes me feel sad that so many women who could have done better in life before me could not do it because of adverse circumstances and lack of opportunity.”

Now preparing to go on a scholarship to Canada, she will try to become an activist too — a cause that is very much supported by her mother, Amina Khatoon, who told Arab News she had “always believed that redemption lies in education” and would always encourage her children to learn.

“She can be the voice of the Rohingya people,” Khatoon said. “She is my only daughter, and I am proud of her.”

Johar added: “I can be a voice for voiceless women. I want to inspire other girls in my community to pick up education.”

Among young Rohingyas in India, she has already achieved the goal. Sabber Kyaw Min, founder of the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, told Arab News: “Tasmida has inspired the whole community ... More and more boys and girls want to study and emerge as voices of the community.”

Priyali Sur, an activist and founder of The Azadi Project, an Indian non-governmental organization that works for refugee rights, said Johar was now “an example for the community” after achieving the feat in an “extremely challenging situation.”

She added: “If we want more women like Tasmida, refugee women who are coming ahead and getting the education and being able to give back to the society, we need to help them, and we need to make sure that our policies are such that their education is not inhibited or curtailed.”