The Tory party conference in Birmingham last October was a bizarre affair by any reckoning. Liz Truss’s leadership had already been self-torpedoed, her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, was just about to be thrown overboard, and there was a palpable need for someone to rally the troops.

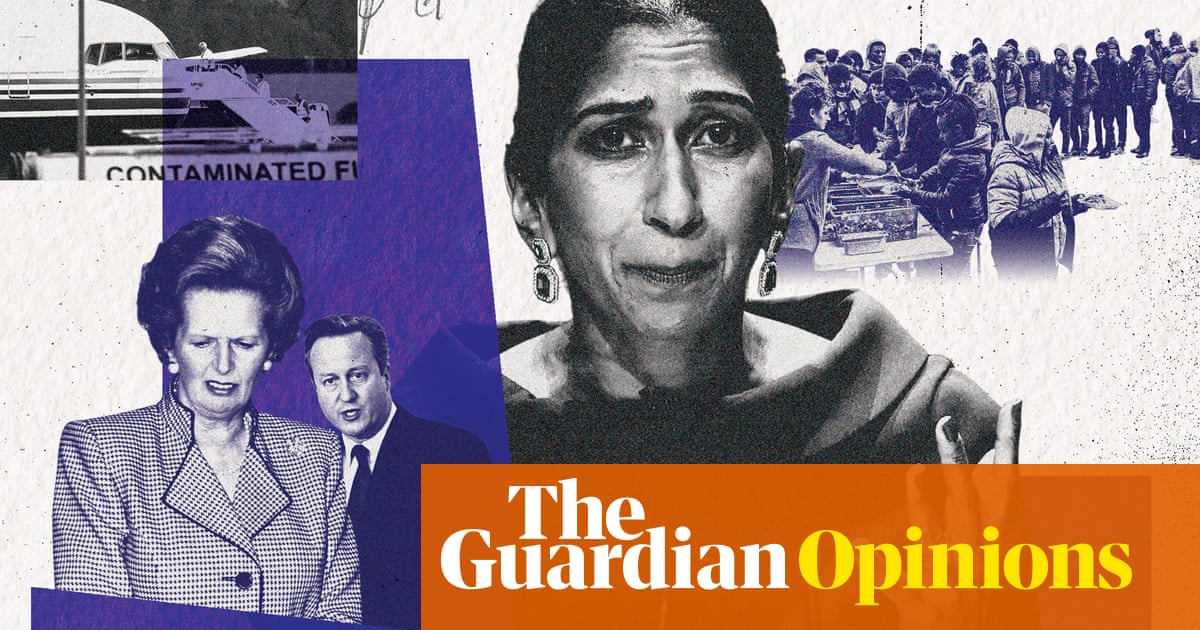

The home secretary, Suella Braverman, was a month into the job and hardly a household name. A diminutive figure with a bloodless style of delivery, she wasn’t an obvious candidate to raise spirits. Addressing the conference in a true blue dress against a royal blue backdrop, she didn’t exactly stand out, and her speech was a predictable mixture of foreign criminals and system-gaming lawyers that brought dutiful applause from the hall, rather than outright acclaim.

But like Martin Luther King, she had a dream, although it was later at a discussion organised by the Daily Telegraph that she chose to share it.

“I would love to be having a front page of the Telegraph with a plane taking off to Rwanda,” she announced to the small gathering. “That’s my dream, it’s an obsession.”

That was the speech that made the headlines, and she hasn’t stopped making them since. Last month was a typically busy one. It started with her vow to stamp out grooming gangs, which she described as “almost all British Pakistani”, and ended with her linking small boat migrants to drug dealing and prostitution. In between she renewed her attacks on Just Stop Oil, introduced new legislation against protest tactics, and oversaw the passage of the national security bill. Among all this activity she also found time to admonish Essex police for seizing golly dolls from a pub.

Essex police later claimed that the home secretary had made no such complaint, but the story was out there, and Braverman had let it be known that she was furious with the police for confiscating dolls, although she would later have nothing to say about police holding peaceful protesters in custody for 16 hours during the coronation.

Gollygate was another tactical skirmish in the ongoing culture war in which Braverman has become the Tory party’s frontline commander. As home secretary, she has turned herself into the darling of the Tory membership and liberal Britain’s chief bete noire. And she’s done it with such attention-stealing conviction that it’s almost as if her predecessor, Priti Patel, never existed.

The Irish journalist Clar Ni Chonghaile has suggested that Braverman “embodies a strange brand of cruel”, and sometimes it has seemed as if her main motivation has been to get up the noses of what she calls “the Guardian-reading, tofu-eating wokerati” – ie anyone to the left of the Tory party.

But there are also Conservatives who think that she’s gone too far. Last December, Nimco Ali, the social activist and godmother to Boris and Carrie Johnson’s son, quit her post as a Home Office adviser, saying that Braverman was “normalising” the politics of Nigel Farage. Ali felt that Braverman showed a lack of humanity by locking “people up in places with no beds, in order to look tough on immigration”.

The former co-chair of the Conservative party, Baroness Warsi, has said that her “use of racist rhetoric” shows that she is “not fit to hold high office”. And another former Tory minister has simply called Braverman a “real racist bigot”.

On top of those voices, last week during a heated debate in the House of Lords on the illegal migration bill, the Archbishop of Canterbury called the proposed legislation “morally unacceptable”.

These are not trivial accusations; yet if, as seems likely, the Conservatives lose the next general election, she could well become the new party leader. One former Tory minister, who speaks of her “gormlessness” and “fanaticism”, thinks such a development would be “completely catastrophic” but nonetheless highly plausible. For more than any other politician, Braverman is a polarising totem of our times.

Sir John Hayes, the Conservative MP to whom Braverman sent the email containing confidential cabinet information that prompted her resignation from Truss’s beleaguered government, says she is “the intelligent voice of the unheard”.

Like many who know her, he rejects the idea that she is cruel, and instead extols her decency. “She is deeply kind, very bright and remarkably brave,” he says.

The question is: how and why did this low-key, quietly spoken planning law barrister come to be the most divisive figure in British politics?

Braverman is from a strong Conservative background, although not the sort rooted in the shires. Her parents were members of the Indian diaspora that was a legacy of the British empire Braverman stoutly defends. Her mother, Uma, came from Mauritius and her father, Christie Fernandes, from Kenya (or “Keenya”, as Braverman pronounces it). They arrived in the UK in the 1960s, during a period of strong anti-immigrant sentiment, “with absolutely nothing,” as Braverman has said, “and it was Britain that gave them hope, security, and opportunity.”

Determined to adopt British culture, the Fernandeses named their daughter after a character in the most popular show on TV in 1980, Sue Ellen from Dallas. To saddle your only child with the moniker of a neurotic, gun-wielding alcoholic may seem an odd choice for such an upstanding couple, but in the event Braverman’s schoolteachers began using “Suella” and it stuck.

She grew up in Wembley. Uma, who twice stood unsuccessfully to be an MP, worked as a nurse for the NHS and as a Conservative councillor. The family, say friends, was and remains a tight one, and although they were not wealthy, Braverman was sent to the fee-paying Heathfield school in Pinner on a partial scholarship.

A friend of Braverman’s from her teens is Alan Mendoza, executive director of the foreign policy thinktank the Henry Jackson Society. Back in 1995, when many teenagers were fans of either Blur or Oasis, the pair of aspiring young Conservatives followed a very different kind of cultural figurehead, the then 70-year-old former headmaster turned populist rightwing MP for Brent North, Sir Rhodes Boyson.

“We were both a little abnormal in being involved in party politics,” admits Mendoza, who says that he and Braverman not only leafleted for Boyson but also read his books.

With his trademark mutton-chop sideburns, Boyson enjoyed a prominent media profile in the 1980s and 1990s, and was seldom shy of expressing his opinions – anti-immigration, anti-comprehensive schools, pro-corporal punishment. He was also pro-Clause 28, and believed that Aids was “part of the fruits of the permissive society”.

It was his readiness to hold forth on such topics that led him later to appear on Brass Eye, discussing with Chris Morris whether Batman was a vigilante role model, and on Da Ali G Show lauding the benefits of “getting caned” in school. To Mendoza and Braverman, however, he was not an object of satire but a political hero.

“I certainly think that both she and I would have been called Boysonites at the time,” says Mendoza, “and I don’t think she’s departed much from that.”

Braverman gained a place at Queens’ College, Cambridge to study law, and became president of the university Conservative Association. While she was president, the student newspaper Varsity did what Mendoza calls a “hit job”, running a front-page story accusing Braverman of political corruption. How she faced down her accusers, says Mendoza, demonstrated a resilience that has served her well in high-level politics.

“People underestimate her at their peril,” he says.

After Cambridge, where she became friends with Robert Jenrick, now minister for immigration, she took advantage of the Erasmus programme (discontinued after Brexit) to gain a master’s degree in European and French law at the Pantheon-Sorbonne University in Paris. During a stint in America, she also qualified to practise law in the state of New York.

The headteacher and education reformer Katharine Birbalsingh recalls meeting Braverman on a tube shortly after the 2010 Conservative party conference. They got talking and Birbalsingh invited her to take part in the free school she was planning to set up in Wembley Park.

“She joined the board and she was really committed. She would visit sites with me, go to primary schools and deliver leaflets. None of this was paid. She was just a lawyer at the time, so she wasn’t doing it to be recognised.”

When she became an MP for Fareham in Hampshire in 2015, Braverman stepped back from what had become the Michaela school, but Birbalsingh was impressed by her determination and conscientiousness.

“She’s a really nice person,” she says. “She says things now that I don’t agree with, but in terms of character, she’s very friendly and warm and helpful.”

Charles Falconer, who shadowed Braverman for more than a year when she was attorney general, echoes the latter point.

“She was always nice,” he says.

It was one of two traits that stood out for him. The other, he says, is that “she absolutely hated face-to-face conflict”.

However, that reluctance to discuss differences of opinion has in no way inhibited her from voicing her own. Her early days in parliament were dominated by the approaching referendum on the European Union. Peter Bone, an active Eurosceptic on the Tory right, remembers courting her support in the Commons’ tea room and being surprised by how forcefully she offered it. Unlike many new MPs at the time, she made “a very strong argument”, he says, which, given her dependence on David Cameron’s patronage, appeared to run counter to her career interests.

In fact, once she became deputy chair of the influential European Research Group in 2016 and then chair the following year, her anti-EU stance almost certainly turbo-charged her ascent. Since Brexit the ERG has exerted hefty leverage on the Tory leadership, pushing for the hardest of Brexits and jumping on any conciliatory moves.

Braverman’s first role in government, under Theresa May, was parliamentary under-secretary of state for exiting the European Union. After less than a year she quit that post in protest at May’s draft Brexit deal, further enamouring herself to the emboldened Eurosceptic right.

It was in the same year, 2018, that she married Rael Braverman, a manager at Mercedes-Benz. He is Jewish, while Braverman is a member of the Triratna Buddhist order, a sect whose founder has been accused of being a serial sexual predator. She attends the London Buddhist Centre once or twice a month. The couple have two young children.

It was Johnson who appointed her attorney general, the chief legal adviser to the government, a job that involves attending cabinet. That Braverman went from novice backbench MP to such a critical position in so short a period of time is as much a reflection of the turbulent political times as her own talent and ambition.

Brexit had shifted the parliamentary landscape, accounting first for Cameron and then May, before Johnson gained control – if that’s the right word for the chaos that ensued. Alarm bells instantly went off for one former Tory minister.

“I had my doubts that she had the aptitude for the job,” he says.

For her shadow, Lord Falconer, it was her indifference to the law that was most striking. He admonished her after she tweeted in support of Dominic Cummings, who was being investigated by the police for breaching Covid restrictions.

“I said: ‘You can’t do that, you’re the attorney general,’” Falconer recalls. “‘You’ve got to remain a bit aloof when there’s a criminal justice issue.’ She sounded upset when I said that. She was polite but didn’t want to engage on the issue.”

In many respects, says Falconer, Braverman was well qualified for the job. She had more experience of public law than most attorneys general of recent times.

“She is a clever lawyer,” he says. “Whatever people say to you, she is not at all stupid.”

Yet, he says, she would routinely put politics before the law, and on matters like protecting the independence of the CPS or what Falconer calls “the constant law-breaking of Boris Johnson” she “just didn’t want to know”.

“She showed a total lack of interest in the law,” he concludes. “She was a terrible attorney general.”

For many observers, a worrying new precedent was established when she advised Johnson that it would be legitimate to contravene international law by breaking the agreement he made with the EU about Northern Ireland and the internal market.

“Her position as attorney general on the internal markets bill was utterly untenable,” says one dismayed ex-senior minister. “Ninety-nine per cent of lawyers knew it was untenable. She appeared to have no understanding of other people’s points of view whatsoever.”

Alternatively, perhaps she understood perfectly well the seriousness of advising the prime minister to break a legal contract, yet didn’t think that the opposing viewpoint mattered. After all, the party was changing, moving rightwards, becoming more populist, and respect for the rules was not a characteristic that was conspicuously valued in Johnson’s government.

There was in any case a kind of purge under way of what might be termed elitist or metropolitan thinking. As one of Braverman’s supporters puts it:

“We managed to cleanse ourselves at the last election of unreconstructed remainers like Dominic Grieve and Anna Soubry and other curious people,” he says. “But it’s like an infestation: you don’t necessarily get all the pests out in one go.”

He speaks of the party absorbing a lot of “the white working-class vote that was always rightwing but tribally Labour”. And it is with this constituency – often seen as anti-immigration – that Braverman, he says, has forged an important connection.

One of the successes of the modern Tory party is its racial diversity. Not only is it the first party to boast a female prime minister (three) and first minority ethnic prime minister (two, if you count Disraeli), it’s also the first to have a minority ethnic chancellor of the exchequer (four in three years), the first to have a minority ethnic foreign secretary, and the first to have a minority ethnic home secretary (three in four years).

But it’s a diversity that tends to focus on patriotism and sidesteps the challenges that many members of minority ethnic communities face. As the columnist and author Sathnam Sanghera phrased it: “You can make it to the top in Britain as a person of colour, as long as you agree to argue that racism is not a problem, and as long as you’re willing to propound actual racism in your politics.”

Braverman’s supporters reject this analysis, arguing that she is merely presenting Conservative positions and her skin colour has nothing to do with it. Indeed, they say, to deny her the right to voice her politics as a result of her race is itself a pernicious form of racism. Yet the way that one of her camp expresses this sentiment is in itself revealing.

“There is an invisibility about her race,” he says. “She’s as English as I am.”

Never has Braverman appeared quite so English as in her role as home secretary. She was appointed to the job by Truss, after Braverman had showed her ambition by standing in the leadership contest.

“What previous attorney general has ever gone for the leadership of the country in the way that she did?” asks Falconer. “She’s got enormous political courage.”

Home secretary was the consolation prize for supporting Truss in the leadership run-off. She has since spent much of her time and energy on the issues of asylum seekers and illegal migrants. Although she inherited the small boats problem and the Rwandan resettlement policy from her predecessor, Patel, Braverman has heartily embraced the issue, placing it at the very top of her strategic to-do list.

“Whether it’s personal ambition,” says Falconer, “or a profound belief that she has the pulse of the nation, she’s doing it in the context of a very clear and determined desire to be the leader of the Conservative party, and the prime minister.”

Last October, a day after a migrant detention centre was petrol-bombed in Dover, Braverman spoke of “stopping the invasion on our southern coast”. It’s this kind of provocation that led Baroness Warsi to say that “Braverman’s own ethnic origin has shielded her from criticism for too long”.

In truth, she’s received plenty of criticism, but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that her ethnic origin has helped her circumvent the issue of racism, and thus served to legitimise an anti-migrant discourse.

One friend thinks that the flak she has received as a rightwinger, in particular about betraying her migrant roots, may have served to push her still further towards an embattled mentality.

“She didn’t strike me as someone who was going to take on a whole bunch of haters,” says Birbalsingh. “I imagine that that has happened to her because she’s being attacked so much.”

When he replaced Truss as leader, Rishi Sunak immediately reappointed Braverman as home secretary, a week after she had been forced to resign for leaking cabinet discussions on immigration to Hayes. If the transgression was worthy of expulsion one week, it’s hard to see why it wasn’t a barrier to re-employment the following one. But politics had grown so feverishly weird by the time Sunak entered No 10 that any eventuality seemed possible.

“I’d have preferred not to see her reappointed,” says one well-placed Sunak sympathiser, “but I am mindful of the fact that the prime minister has an enormous problem, as he has about 60 MPs who probably shouldn’t be in the Conservative party.”

For their part, Braverman’s supporters are quick to point out that the policy on migrants is endorsed by Sunak, and they certainly won’t let him forget that he has tied his fortunes to hers.

If Braverman is callously targeting migrants, the concern about the small boat Channel crossings is not entirely confected, for, according to Bone, it’s the complaint that comes up most often with his constituents.

“If the government doesn’t fix it,” he says, “I think we have very little chance in the next election.”

More than 45,000 people made the Channel crossing last year, which is a substantial number. But it’s also within the context of net migration to the UK last year of more than 500,000 (with an estimate of a record 700,000 for this year).

“The system is broken,” said Braverman six months ago, after almost 13 years of her party being in power.

One of the tensions that deepened between Braverman and Truss is that in her push for growth, Truss needed high levels of immigration to compensate for lost labour following Brexit. The Tory right was split between Truss’s economic libertarians, who wanted the market to decide on migrant numbers, and Braverman’s supporters, who demand strict controls.

Braverman still wants to see numbers coming down to the tens of thousands, but as that is not going to happen anytime soon, it leaves her with the emotive issue of refugees – or illegal migrants, as she prefers to call them. In reality, it’s easier to demonise the occupants of the small boats than it is to prevent them from coming. The threat of a fraction being sent to Rwanda won’t discourage those desperate enough to take to the sea.

As David Normington, a former chief civil servant to the Home Office, noted last month: “Even if they know about the Rwanda policy in general terms, today’s asylum seekers are not going to be deterred by the theoretical threat – or, if it comes to pass, the practice – of deporting a few hundred people a year to Africa.”

“What you need to do is get asylum seekers processed in a reasonable time,” says the former Labour home secretary Alan Johnson, for whom Normington worked. “By the time we left office, 80% of them were being processed within six months.”

The backlog on asylum cases is currently 160,000 and growing, with the system getting slower and less efficient. Of course, dealing with all that and persuading the French to halt people traffickers, much less addressing the international instability that causes refugees and migration, requires a combination of quiet determination and effective diplomacy, neither of which have been in abundant supply in government in recent years.

The paradox is that Sunak, who presents himself as the understated technocrat, is reliant on a crude, headline-grabbing policy to maintain his credibility. For Braverman it’s more like a win-win situation. If her Rwandan dream comes true, and if the small boats are somehow thwarted, then she can claim the plaudits. But if the whole thing never gets off the runway, the lawyer can blame the law and Sunak’s unwillingness to confront, or remove the UK from, the European court of human rights.

“A big problem the party has,” says a former senior minister, “is that its membership is now at very significant variance in their attitudes to the people who vote for it. If they selected Suella as the leader of the party, the rupture would be very considerable.”

Yet Braverman’s team, one told me, calculate that Tory voters are now to the right of the membership, and it’s the MPs who are out of touch. The Tories could be poised to enact the kind of grassroots revolt that brought Jeremy Corbyn to power in the Labour party, though not, they may care to recall, in the country.

That Braverman takes pride in saying things that a more temperate or empathetic politician would never think to express is beyond denial. But it would be wrong to assume that it’s a cynical career manoeuvre, or that she has adopted racist rhetoric so as to make her own racial identity acceptable to the Tory right.

As confounding as it may be to liberal ears, those who know her all agree that she genuinely believes what she says. Her mentor, Boyson, once wrote a book calling for the end of all immigration except refugees. That, more or less, has always been this daughter of immigrants’ position. The only difference is that, Ukrainians and Hong Kong citizens aside, she no longer sees refugees as an exception.