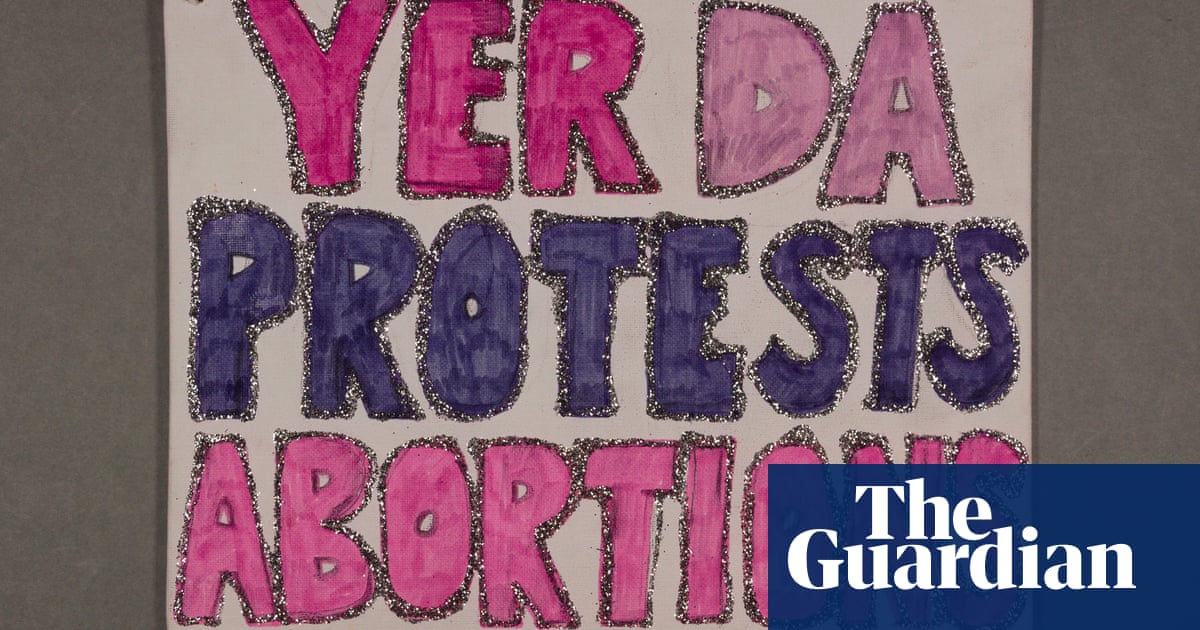

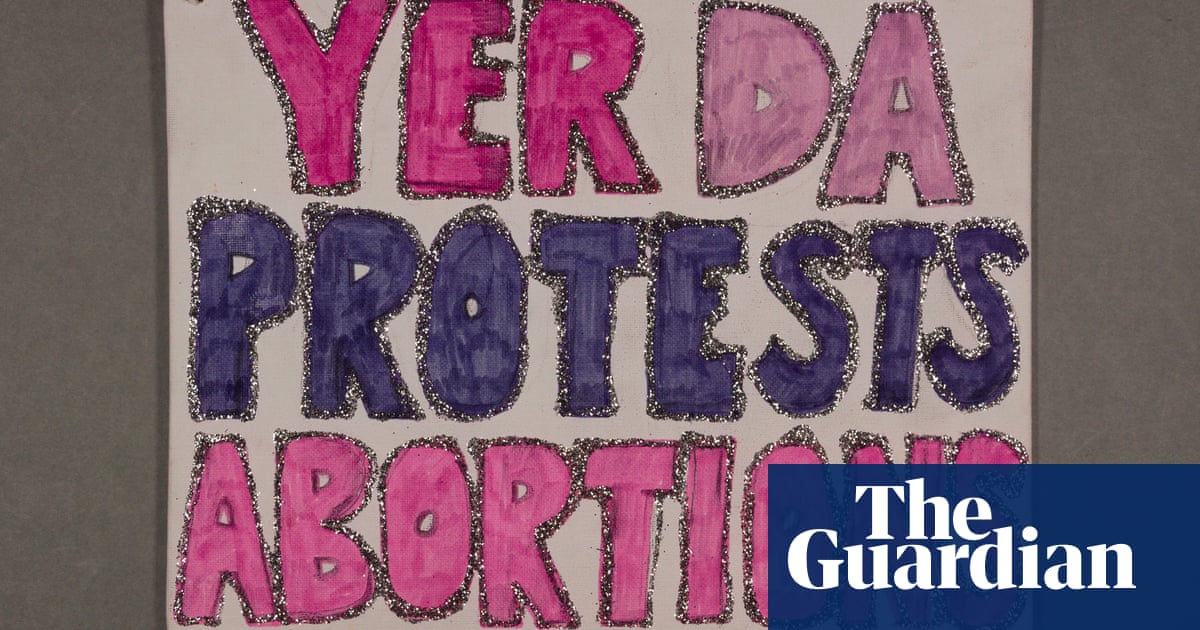

Last month, more than 100 anti-abortion protesters arrived at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow to be met with a formidable opposition: just behind their usual gathering spot the railings had been converted into a huge, multi-coloured mural made up of banners peppered with irreverent messages such as “No womb for your opinion”, “Keep your rosaries off my ovaries” and “Yer da protests abortion”. There were recurring visual motifs, many used in abortion rights campaigns for decades, such as a cartoon uterus giving the finger, wearing a sombrero (“Nacho uterus, nacho business”), or gleefully booting a foetus. Within a day, images of the protest and its flamboyant backdrop were splashed across Scottish newspapers.

The creative counter-protest caught the attention of Glasgow Women’s Library, which collects banners, badges and other ephemera from across the women’s liberation movement, many predating the organisation’s founding in 1991. You’ll find beautiful placards and pins there, from the original abortion rights movement of the 1970s to the Repeal the 8th campaign to lift the abortion ban in Ireland. When they saw the colourful displays from the recent Glasgow protests, they agreed to archive many of the protest materials as important social-historical documents and artworks in their own right.

In their overflowing archive room, Jenny Noble, museum curator at the library, and archivist Nicola Maksymuik, talkme through their work. “We have a special indexing system here to reflect the vast range of women’s experiences,” Noble explains. This system, designed by the organisation’s librarian Wendy Kirk, is based on Indian and Austrian feminist classification models. It includes headings and subheadings like “feminist/lesbian/queer aesthetics” and “LGBTQI history and culture”. This allows items to be archived in a way that better reflects their cultural significance. “Also, like lots of libraries, we’ll cross-reference items,” adds Maksymuik. “So if a protest banner arrives that has an amazing design, or is beautifully stitched, that will be recorded as an artwork as well as a social document.”

Traditionally, movements for political change have been accompanied by flowerings of creative activity (Jo Rippon’s 2019 book The Art of Protest provides a good introduction). The Women’s Library archive holds items that are undeniably works of art. These include textile artist Claire Hunter’s 1987 banner A Woman’s Place Is in the World, made for the miners’ strikes, the One World Quilt stitched by the Black Environment Network in 2000, and a sign reading “Solidarity From Glasgow” painted by Niamh Forbes for Repeal the 8th. The library has also collected materials made by Shetland art collective Gaada for their Up Helly Aa for Aa campaign to allow women’s participation in the islands’ traditional fire ceremonies.

However, when the library chose to collect materials from the Queen Elizabeth protest it was predominantly because of the pivotal period in Scottish and global women’s history that they seemed to reflect. Organisations such as Back Off Scotland and Humanist Society Scotland (for which I work part-time as communications manager, as well as being an arts journalist) are currently pushing to introduce protest-free “buffer zones” around abortion clinics in Scotland, to match similar legislation that already exists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. If a bill introduced by Green MSP Gillian Mackay passes through Holyrood this year, protests like last month’s – which many see as religiously motivated harassment – will no longer be legal. As the legislative net threatens to close around the Scottish anti-abortion movement it has redoubled its public agitation, particularly during Lent this year, when rolling abortion-clinic protests were staged under the banner of “40 Days For Life”. Pro-choice campaigner Gemma Clark wouldn’t call herself an artist, but believes there’s much to be gained from making creative materials to counter such attacks on women’s rights. “Having to fight for your basic rights all the time is exhausting,” she says, “and so making signs is quite mindful. Plus my bubble-writing skills as a primary school teacher have come in useful!” She agrees that the recycling of designs and phrases across materials is a bit like folk art, with ideas contributed anonymously to an evolving collective lexicon. “When I was at a rally in London my sign said ‘Forced birthers are modern day witch-prickers’, and I’ve seen a few witch-themed signs since then. I’m like, ‘Did I start that?’”

Clark decided to take up a public voice on abortion rights after the overturning of Roe v Wade in America. “I remember looking at the girls in my class the day after and thinking: you have no idea what just happened, and you deserve so much better.” To counter the protest outside the Queen Elizabeth (which offers abortion services), she and her husband, Douglas, coordinated with Cabaret Against the Hate-Speech, or Cath, a group that plans karaoke singalongs for counter-protests. Cath gathered dozens of signs from previous women’s and trans rights marches and also put a call out for new ones. At 7am on the morning of the vigil they affixed the signs they’d collected to the long fence behind where the crowds congregated. Because the British Pregnancy Advice Service advises against live counter-protests, this strong visual presence made pro-choice opinion clear. It also spoke to the heightened stakes of the abortion-rights conflict in Scotland, where Kate Forbes, a Free Church member who opposes abortion, came within a whisker of becoming first minister.

Whether the materials from that day are recorded as artworks or something else doesn’t really matter, Noble tells me. “It could be a really intricate textile piece or something someone’s written on cardboard with marker pen … it’s all valuable. I think a lot of women don’t realise that when they make these things they’re participating in women’s history.”