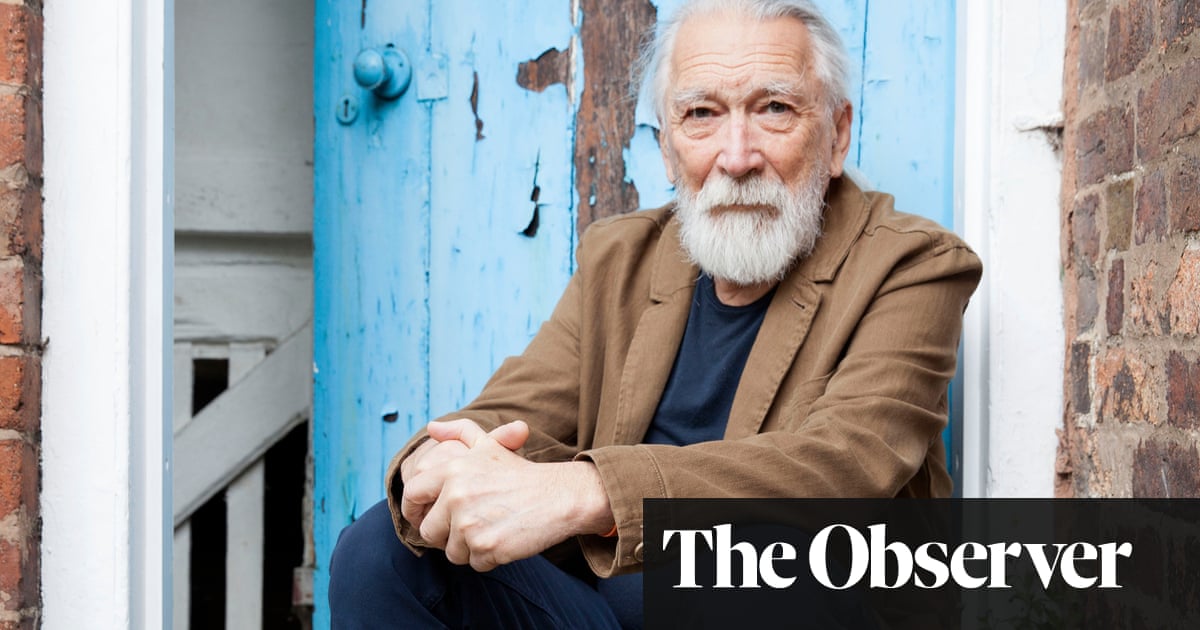

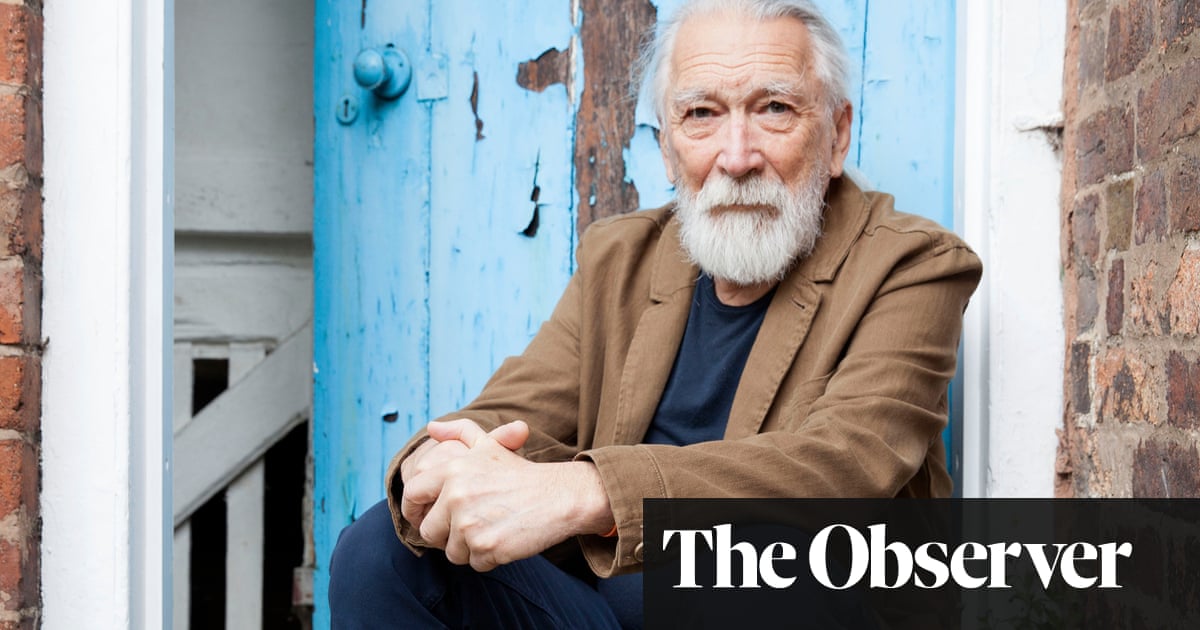

MJohn Harrison, 77, is the author of seven story collections and 12 novels, including Nova Swing, which won the Arthur C Clarke award for science fiction in 2007, and The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, winner of the Goldsmiths prize in 2020. His new book, Wish I Was Here, is a fragmentary work of autobiography about reading, writing and, among other topics, rock climbing, a longtime pursuit that inspired Climbers (1989), which Robert Macfarlane has called “the best novel ever written” on the subject. Harrison, speaking from his home in Shropshire, told me he took up the activity in his 30s to “blast myself out of writing and into what I thought of as the real world. Because if you let go from 50ft up, the consequences are real. The mistake I made was to immediately sit down and write about it.”

What drew you to the subtitle “An anti-memoir”?

I wanted to talk about how I perceive memory, and especially the writing down of memory, to be a failed device. You make a note about something you want to remember and all you end up with is a fiction or a hyperbolic representation of what happened. And the moment you use it for any purpose, it goes through further transformations, and by the time you’re finished with it as a 77-year-old author, the memory you have when you look at the note isn’t really a memory at all. But you can’t really call it a fiction – it’s a hybrid thing. That’s what I wanted to produce. Calling it anti-memoir isn’t a form of trolling; it’s saying, let’s think a bit more about this complex business of relating what we think of as a self to what we think of as a past.

Yet, judging by the book, is it right to say your sense of self was never simple?

As a child I always felt dissociated, or not associated, not plugged in. It troubled me that adults were more articulate than me and therefore always more capable of dealing with the world than I was, particularly when there was a conflict between me and them. Feeling dissociated was difficult enough on its own but to then feel you’ll never be able to speak about it, or anything else for that matter, because everyone you meet will always be more articulate than you… I think the urge to be a writer develops out of those conditions.

You write at one point: “You go through the doors that open.” Was that key to your becoming a science fiction writer?

It was complete serendipity that the first magazine that accepted a story of mine was a science fiction magazine. I was reading tons of science fiction but I was equally obsessed by a religious novelist called Charles Williams, who was connected to Tolkien, and I was also reading Robbe-Grillet, Alan Garner, CS Lewis, JG Ballard, picking and mixing to produce what I thought of even then [in the 60s] as an arena of my own in which to work. Only science fiction and fantasy magazines, and the occasional experimental magazine like Ambit, would receive that kind of hybrid work.

Ballard and Brian Aldiss and Michael Moorcock with [the magazine] New Worlds wanted to show that science fiction or fantasy could talk about serious things. I was enthusiastic about that idea, and angry. I felt like I’d stumbled into a war and was probably angrier than Ballard, who was too busy simply getting on with actually doing it to have a war with anybody.

The book says in passing that Cormac McCarthy’s The Road seemed to you a “waste of the power of the big visionary-apocalyptic machine”.

The Road was basically out of that early tradition of postapocalyptic fiction started after the second world war by John Wyndham. Ballard had deconstructed all that by the time I came on the scene; the idea that disaster happens and you rebuild what came before, preferably by starting an allotment, was already old-fashioned. He thought disaster would strip everything down and be a doorway to newness and novelty.

I think we’re into another phase now. The disaster probably won’t be explosive but steady, continual and unevenly distributed – so huge that it’s like an elephant in the room nobody can see the whole of. The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again was a disaster story of that type; something’s going on, but it’s too big for anybody to see anything but part of it.

How do you feel about the emergence of AI?

I’d separate the thing itself from the boosterism around it. We’re at a familiar point on the curve when it comes to the overenthusiastic selling of new scientific ideas, where one discovery or tech variant is going to solve all our problems. I’d say wait and see. Meanwhile I’ll be plotting to outwrite it; I want to be the first human being to imitate ChatGPT perfectly. I bet you it’s already got mimickable traits.

What are you reading at the moment?

I’m halfway through Bret Easton Ellis’s new novel, The Shards, which is a very interesting sort of intellectual horror; I’ve always liked how he mixes the frame with the fiction so that you’re constantly questioning what’s real and what isn’t. But I’ve been tired because I read 170 books last year to judge the Booker and had to essentially produce a review of each one to argue with five other people about them. Going into a room to discuss 20 books in two or three hours [for each session] was enjoyably intense but left me exhausted. Very few books on that list I’d actually have read myself, so I was being introduced to a lot of reading I normally wouldn’t have done at all.

In the book, you mention something about “losing the war with chocolate”.

My relationship to chocolate is that of an addict. I looked down one day from climbing a limestone route in the Peak District having heard jackdaws and thought: “What are those fuckers up to?” They’d got the rucksack open and were pulling out the Mars bars, stripping the package off and eating them. You can’t do anything about that when you’re 80ft up and tied to a rope. The jackdaws have won.