‘I wanted to see if the plants could contribute something,” says Hito Steyerl, sitting in the office of her Berlin gallery. “I feel it’s a good idea to take humans out of the equation a bit.”

Described as a post-internet artist – someone who uses the tools of digital technology to tackle broader social issues beyond web culture –Steyerl is credited as the creator of one of the works in Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis, a new group show at London’s Hayward Gallery. But in a way the true creative force behind the piece, called Green Screen, isn’t her at all. It’s not even human. On the back of a giant LED screen, Steyerl has grown a vertical garden with ferns and hops. The plants generate bioelectrical signals, which are translated into sounds that have been paired with a rudimentary drum track. The results, which come warbling out of a pair of speakers, are fed into an AI engine that turns them into heavily pixelated animations of budding flowers.

Taking humans out of the equation, making art that is a sort of disappearing act, harks back to what is probably Steyerl’s best known work, the 2013 film How Not to Be Seen, in which she hides behind placards, covers her head with cardboard boxes, and smears herself with face paint, allowing her to blend into a green screen. Meanwhile, a rasping robo-voice offers satirical advice for “how to be invisible by disappearing”. The tips include “living in a gated community”, “being fitted with an invisibility cloak” and “being female and over 50”.

It’s fair to say this strategy isn’t working for the now 57-year-old artist: the more Steyerl tries to disappear, the more visible she becomes. Four years after she finished How Not to Be Seen, she became the first woman to top ArtReview magazine’s Power 100 list, for her “political statement-making and formal experimentation” (last year’s list still has her at fourth place). Her renown on the international stage led her to be courted in political circles in her native Germany. In 2021, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the country’s president, offered her its highest honour, the Federal Cross of Merit. Steyerl declined in protest at how Germany handled Covid, calling its partial lockdown “half-baked and endless”.

Her shows – or the comments she makes around them – tend to start debates that reverberate beyond gallery spaces. Last year, she pulled her art from the giant Documenta show in Kassel over a scandal about another work condemned for its antisemitic imagery – a decision that contributed to the exhibition director’s resignation and catapulted her from the arts sections to the front pages.

The main reason why Steyerl finds it hard to stay invisible, she says, is that her idea of art relies on saying out loud the bits that others may keep quiet about. “I think my approach is best summarised with the colloquial elephant in the room. These elephants are everywhere, but people pretend they aren’t there. That’s something that irritates me in a fundamental way.”

For her 2019 solo show at London’s Serpentine Gallery, Steyerl filmed a series of videos in which activists wander through surrounding Kensington, the richest borough of a city that, according to Forbes, is home to more billionaires than any other in Europe. The activists talk about disability rights, the exploitations of the gig economy and welfare cuts. An augmented reality phone app visitors had to download removed from the gallery’s facade the name of the Sackler family, whose record of donating to the Serpentine and other institutions has been overshadowed by its role in America’s opioid addiction crisis. The Serpentine physically removed the name three years later.

The instinct to drag taboos out of the shadows and into the daylight has been with Steyerl ever since she was a teenager. Born in Munich in 1966, to a physicist German father and a biochemist Japanese mother, she grew up in the “democratorship” of Bavaria under Franz Josef Strauss, the strongman state premier. “I was surrounded by elephants: the Nazi past of politicians, corruption, incredible police violence, repression against outsiders.” She was expelled from school aged 15, after squatting a building and throwing stones at a Deutsche Bank, and didn’t finish her secondary education.

Does she see art as a way to point a finger at social injustices, to educate people? “No,” she says instantly. “It would be pointless if art worked like that. If you want to make a difference with art, which is a motive I perceive as questionable, then the single most stupid approach would be to tell people off. It would be a surefire way not to get through to people. And it would be the opposite of thinking.” She pauses and adds: “I don’t like being lectured – and I expect my viewers don’t either.”

The full title of Steyerl’s disappearance film was How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, but whatever didacticism her work contains is never taken too seriously. Sometimes confusingly so. During our interview, choppy industrial metal chords echo from her exhibition in the room next door. This is Contemporary Cave Art, a site-specific version of the film installation she withdrew from Documenta.

Defying description, the work bubbles with ideas, drawing connections between Keynesian economic theory and battle royale video games, not to mention the “Disney ecology” and a satirical cryptocurrency called Cheesecoin. It’s dizzying because that’s how Steyerl wants it: very serious and ironic at the same time. I had to watch it twice before I thought I could trace her lines of thought. In the third viewing, I got distracted by the dancing wolves again. It wasn’t the opposite of thinking, but it wasn’t quite thinking either.

What sets Steyerl apart from other activist artists is that she puts her money where her mouth is. Last year, she bought back one of her works from Julia Stoschek, a collector of video art and an heir to the car parts company Brose. Steyerl made her decision after an interview in Der Spiegel in which Stoschek defended her company, which was accused of not doing enough to investigate how her great-grandfather Max Brose, a Nazi party member, had profited from Jewish expropriations and slave labour in the Third Reich.

Declining the Federal Cross in 2021, Steyerl criticised the German government for not offering equal support for artists across the board during the pandemic’s lockdown months. Two years on, she says she would do the same, while accepting that government support in Germany was comparatively generous. “My gallery was open,” she says, “but music schools for children remained closed. That wasn’t fair. I’m aware that there was a lot of state aid for commercial culture. But non-commercial culture was left by the side. I am aware artists and institutions in the UK had a much rougher time. But is this a sufficient reason for accepting a German decoration?”

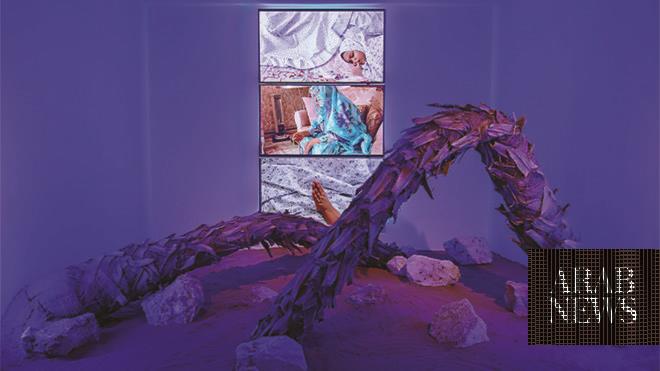

Green Screen, which sits alongside works by Cornelia Parker, Richard Mosse and Otobong Nkanga, is meant to make us think about the materials used to make the screens we all spend so much of our lives looking at. The LED monitor that shows the flower animations generated by the plants on its flipside was almost entirely built by Steyerl herself, based on a prototype originally developed by a Berlin hacker collective called C-base. It features a wall of beer crates turned on their sides, with the lit-up bottoms of recyclable bottles serving as rudimentary pixels. The LEDs inside the bottles were made in China, Steyerl concedes, but points out that her self-built screen uses about 1,000 lights compared to the 8.3m found in a regular screen.

“It’s an experiment and a prototype,” she says, “a visualisation of a question, not a solution. I tried to think about how we could extricate ourselves from our dependency on the large tech cartels.” These cartels, she argues, “steal our data and use it for their personal ends. They polarise and poison our public discourse. In the context of the show, one of the big questions is around the ecological footprint, the question of what kind of materials are used in TV or LED screens.”

Given that Steyerl makes electricity-hungry video installations in the middle of an energy crisis that has left households across Europe facing saving targets, it’s a question that could also be directed at her. When I email a followup question about the carbon footprint of Contemporary Cave Art, she responds within three hours – with a calculation of the greenhouse gases generated by computers, screens and projectors, which comes to around 200kg of CO2. She also lists the steps she took to reduce this, by forsaking a flight, for example, or recycling elements from other shows.

One way to explain Steyerl’s rise to prominence is that few other socially conscious artists are so energetically engaged in an argument to justify their own existence. In my followup, I also ask whether holding herself accountable, applying the same standards to herself that she applies to others, is sustainable in the long run. Does it spur her on? Is there not a point where it will get too exhausting?

“As a dialectical materialist,” she writes back, “I do not believe that social contradictions can be solved individually. On the other hand, if you give up on trying to articulate them altogether, you end up being depressed and cynical. So you navigate between different impossibilities and keep failing in all directions, obviously. But what’s the alternative?”

Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis is at the Hayward Gallery, London, 21 June-3 September