Despite initial denials by both countries, Iran confirmed this week that it engaged in indirect talks with the US in Oman last month over Tehran’s nuclear program. Several Western media reports confirmed that US Middle East coordinator Brett McGurk and Iran’s top nuclear negotiator Ali Bagheri Kani were in the Omani capital, Muscat, at the same time in early May and that Omani officials acted as intermediaries. Both the US and Iran denied that talks centered on reaching an interim agreement, with Iranian officials insisting on reviving the 2015 nuclear agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. That agreement, which the Trump administration pulled out of in 2018, was endorsed by UN Security Council Resolution 2231 in July 2015.

According to American reports, the US passed a message to Iran that it would face a severe response if it reached the 90 percent uranium enrichment levels required for use in a nuclear weapon. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran has at least 114 kg of uranium enriched up to 60 percent purity. Israel has also warned that it will never allow Iran to come close to the 90 percent enrichment level.

Following US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Saudi Arabia last week, which must have focused on threats posed by Iran’s nuclear program, and the leaking of reports regarding possible progress in negotiations, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told Blinken that Israel would not be bound by any agreement with Iran and that it would take the necessary steps to protect its national security.

On the other hand, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said earlier this week that a deal with the West over the nuclear program is possible, but only if Tehran can keep its nuclear infrastructure intact. Since the US pulled out of the 2015 agreement and imposed sanctions, Iran has installed advanced centrifuges and raised its uranium enrichment levels to more than 60 percent. It has also prevented IAEA monitors from inspecting some facilities and is believed to have built new ones and expanded others.

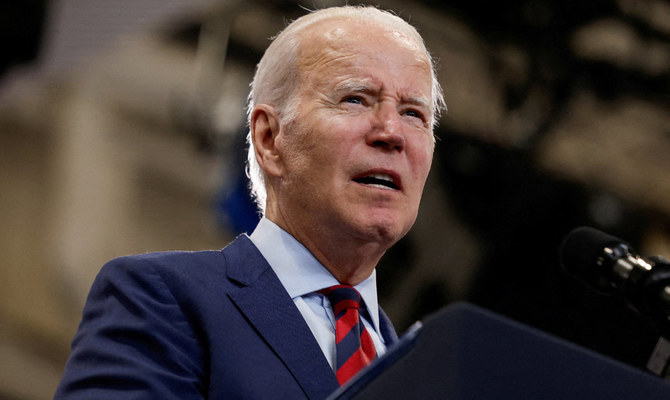

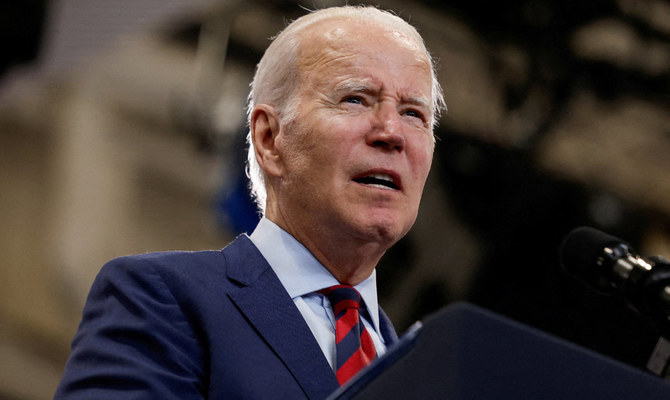

Previous attempts by the Biden administration and Western partners to engage Iran in a bid to reach a new agreement were unsuccessful. Iran insists on reviving the 2015 agreement, while the West wants to tie the agreement to other issues, such as Tehran’s controversial ballistic missiles program, curbing the regional activities of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and allowing the IAEA to carry out a full investigation of Iran’s nuclear facilities.

For a while, it looked like the Biden administration was no longer interested in pursuing further talks with Iran. But a number of factors have forced it to reengage. Russia’s war in Ukraine has brought Moscow and Tehran closer than ever and Iran is believed to have supplied Russia with advanced drones and is helping the Russians build a drone factory. In return, Tehran may get its hands on a first batch of state-of-the-art Su-35 fighter jets from Moscow as early as this month. And Iran last week unveiled a hypersonic missile it claims can hit Israel in 400 seconds, while outmaneuvering the Iron Dome defense system. The technology to develop such a sophisticated system could only come from Russia or North Korea.

Iran insists on reviving the 2015 agreement, while the West wants to tie the agreement to other issues.

Osama Al-Sharif

Also, the recent China-mediated deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran to normalize ties took the US by surprise. Relations between Riyadh and Washington have gone through some rough periods since President Joe Biden was elected, while the Saudis have adopted an independent foreign policy approach that has seen improved ties with both China and Russia. Feeling its regional influence waning, Washington has made an about-face; seeking to revive ties with Riyadh and sending its top diplomats there.

The thaw in Saudi-Iranian ties has been reflected in the Gulf region and beyond. Earlier this month, the commander of Iran’s naval forces, Shahram Irani, announced that Tehran was looking to form a joint maritime alliance with the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Iraq, Pakistan and India. Saudi Arabia was also interested in “heading in this direction,” Irani said. The announcement came a few days after the UAE decided to quit the Combined Maritime Forces led by the US.

The change in Washington’s attitude toward talks with Iran underlines its geopolitical concerns, as well as fears that the suspension of the nuclear deal has only played into Tehran’s hands in many ways. US threats of resorting to force against Iran are no longer in sync with regional developments. Its key allies in the region, save for Israel, are now actively talking to Iran, with some, like Egypt, on the verge of restoring ties with Tehran.

These allies are now in favor of a diplomatic resolution to the Iran nuclear program issue. This week, the Gulf Cooperation Council issued a statement calling on Iran to commit to working with the IAEA and asking for the involvement of the Gulf states in possible negotiations to meet the bloc’s security concerns.

Interestingly, the US seems to have allowed Iraq to release about $3 billion to Iran in overdue payments — a sign that some of Tehran’s demands are being met. Also, a prisoner exchange is expected to take place between Iran and the US in the coming days, according to Iranian officials.

A deal, whether interim or not, would be good for the region and for the world. But it might not help Biden and the Democrats in the coming election cycle. Both will get a lot of flak from Republican candidates, as well from the current Israeli government. This week, a bipartisan letter from 35 members of Congress called on the European parties to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal to “snapback” sanctions on Iran for noncompliance.

In fact, any agreement reached will almost certainly give former President Donald Trump and other Republican hopefuls the ammunition to tear down the Biden reelection campaign. This is how hard it will be for the White House to decide its next move. Not doing anything carries the risk of Israel and Iran finding themselves in an open war with an unpredictable outcome. Securing a deal would harm Biden’s election chances, while the return of Trump or a Republican hard-liner to the White House might make any new agreement a short-lived one anyway.

• Osama Al-Sharif is a journalist and political commentator based in Amman.

Twitter: @plato010