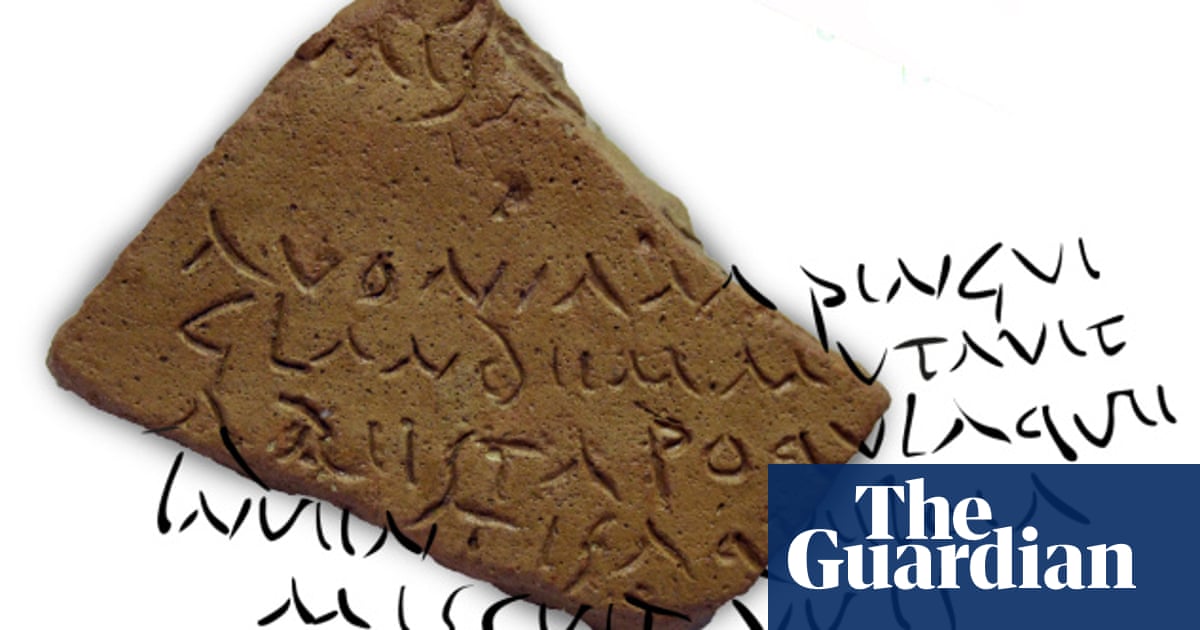

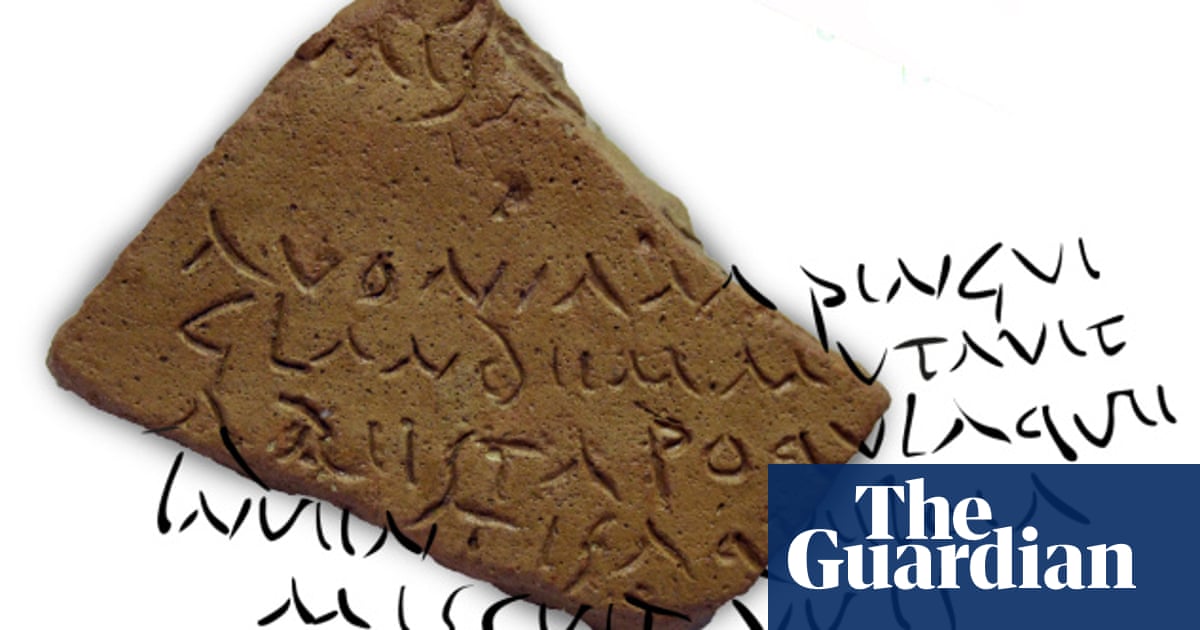

A tiny fragment of a Roman jar that once held olive oil, produced in what is now southern Spain, has left archaeologists delighted, puzzled and “saucer-eyed” after they deciphered a quote from the ancient poet Virgil that was cut into its clay by an unknown but erudite hand 1,800 years ago.

The highly unusual find, thought to be the first time a literary quotation has been discovered on a Roman amphora, was turned up by researchers from the universities of Córdoba, Seville and Montpellier who were excavating a site in the town of Hornachuelos, in Andalucía’s Córdoba province, seven years ago.

While the ceramic vessels were routinely engraved with information relating to producers, quantities and taxes, the 6cm by 8cm shard appeared to contain an unusual amount of text.

“We thought it might be something quite exceptional because you hardly ever get more than a line or two of engravings on an amphora,” said Iván González Tobar, an archeologist on the project, which was funded by the Labex Archimède research institute in Montpellier, France, part of Paul Valéry University.

“This one had four or five lines. While we didn’t understand it, we thought it was quite special.”

Subsequent examinations by Latin experts determined that the fragment bore a quote from Virgil, best known as the author of the epic Latin poem the Aeneid.

“To be honest, it took a while because there were some spelling mistakes that held us back from seeing what it was straight away,” said González Tobar, who is now an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona. “But we did eventually get there.”

One of his colleagues, Antònia Soler i Nicolau, thought she recognised the quote – and indeed she did. It turned out to be from the first section of Virgil’s second major work, the Georgics: “[Earth] once changed the/Chaonian acorn for the plump wheat-ear/And mingled with the grape [your newfound gift].”

As far as González Tobar and his colleagues are aware, the fragment is the first time that a line from literature has turned up on a clay vessel.

“There are quite a lot of bricks that have been found with texts from Virgil on them because we think they’d been used for teaching before being used for building,” said González Tobar. “But nothing’s been found on amphorae.”

Given the fragment was found in a rural area where much of the olive oil sent to Rome was produced and bottled, the team thinks Virgil’s agriculturally themed Georgics may have struck the engraver as more fitting that the heroics of the Aeneid.

The researchers’ key theory, as published in the Journal of Roman Archeology, is that the verses, written on the lower part of the amphora, were never really intended to be seen.

They believe the author may have been a skilled labourer or perhaps even a child worker at the factory where the amphora was manufactured. In any case, the lines make it clear that whoever scratched the letters into the clay was more educated than such workers are traditionally supposed to have been.

“We really can’t say for sure why the lines were written, but we do know that they appear on a part of the amphora that wouldn’t have been seen,” said González Tobar.

“Maybe a worker there wanted to show them to a colleague – they could have been done by an adult or a child. What we do know is that this was done inside an amphora factory, and that the lines were probably written from memory.”

According to the journal article – written by González Tobar, Soler i Nicolau and Piero Berni Millet – the small, learned fragment that lay in the Andalucían earth for almost two millennia will be “of exceptional interest for archaeologists, epigraphists, and philologists of [colloquial] Latin”.