It was in 1975, when Carl Resnikoff and his girlfriend, Judith Gipson, took a bucolic ferry ride to Sausalito, a city located on the north end of Golden Gate Bridge, that a revolution in youth culture, music, emotion and imagination would take place. It was on that ride that the two undergraduates took capsules filled with MDMA powder for the very first time. Resnikoff, a biophysics major at Berkeley, had synthesized the drug himself. As the boat cut through the water of the San Francisco Bay, Gipson began to feel “a floating sense of euphoria … like some guy could come walking up to us asking for help and his guts are spilling out, and we’d be grooving on how beautiful it was.’”

According to Rachel Nuwer’s book I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World, Resnikoff and his girlfriend’s romp was the first-ever documented instance of people taking MDMA recreationally.

Nuwer is a science journalist who covered clinical trials for MDMA use in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While cannabis and psilocybin have undergone rebrands of late, going from countercultural tokens to the mainstream, she believes that the public is starting to open up to MDMA, too.

“MDMA deserves its own story,” Nuwer said. “I wanted to bring together the history, culture, politics and science of the drug all in one place. This book is for anyone who’s interested in the drug, whether it’s someone who’s taken it 500 times on the dancefloor or who’s using it therapeutically for the first time.”

Nuwer believes that MDMA will “follow the path of cannabis”, becoming legal medicinally first, then decriminalized, and perhaps fully legalized for all types of use.

That cycle may have already started: three clinical trials have found that MDMA, which is also called ecstasy, can speed the recovery of PTSD. FDA approval for therapeutic use could come as early as next year.

It’s been a long journey for MDMA, once demonized by sensationalist media coverage that turned the rare ecstasy deaths into moral panics, often without mentioning the other factors that made the drug more dangerous. (Most fatalities were caused by dehydration or combining MDMA with other substances.)

Moral panic intensified after a paper published in Science in 2003 found that MDMA caused permanent brain damage in monkeys and baboons – two unlucky animals died from their doses – which did much to advance the stereotype of burned-out rave kids. But, as Nuwer writes, that paper was later dramatically retracted after it was revealed that the scientists had mistakenly dosed the rats with crystal meth, not MDMA.

Scientists called this “the great retraction”, and though the authors of the study blamed their error on mislabeled drug bottles, skeptics wondered if they were trying to cover up a laboratory theft of MDMA that led to the switch-up.

Through her research, Nuwer learned that many things most people think they know about MDMA – even hardened users – is actually false. For one: the name itself. The first nickname for MDMA (or methylenedioxymethamphetamine) was Adam, a nod to its back-to-nature, lovey-dovey effects. Then came ecstasy, which was coined by the massively successful Texas distributor Michael Clegg. Ecstasy was rebranded by dealers in the US in the early 2000s as molly, and some users thought it was a different, or “better”, drug.

But all of those nicknames refer to the same drug. “Some regular MDMA users still swear that molly is different than ecstasy, but it’s not,” Nuwer said. Still, the idea that molly is “purer” than ecstasy led to a boom in sales, bringing the decidedly 90s drug back in the new millennium.

While the tale of two college kids trying MDMA they made themselves on a ferry ride is certainly a fitting origin story for a drug linked to youth culture, other people certainly tried MDMA before they did – those stories are just lost to time.

As Nuwer writes, the drug was first created by Merck, a German pharmaceutical company, which filed a patent for methylsafrylamin on Christmas Eve in 1912. The pharma company was trying to develop a blood-clotting drug, which fell through, but the compound was picked back up in the late 1950s as a potential energy supplement for fighter pilots.

By the 1950s, CIA agents working on MKUltra, the secretive and illegal human experiment program, were at least aware of MDMA’s existence. Though the program may be most famously associated with LSD – agents dosed unwilling participants with the psychedelic in hopes of testing it as a truth serum against Soviet agents – they also used MDA, a close sibling of MDMA.

When Harold Blauer, a 42-year-old former tennis player, checked into a posh Manhattan hospital for depression in 1952, he had the misfortune of doing so at the same time the US army tapped the clinic to study the effects of mind-altering drugs. After four injections of MDA left him chilled, shaking and begging for doctors to stop, Blauer got a final, massive dose of 450mg of MDA. He seized, fell into a coma and died. Doctors tried to pass it off as a coronary attack, which was successful until the truth was revealed by a 1975 congressional inquiry. (Blauer’s family won a $700,000 wrongful-death lawsuit against the government in 1987.)

The incident seems to have cooled the use of MDA in army experiments, and the Controlled Substances Act of 1971 made MDA illegal. Shortly after, chemists tweaked the components of the drug to create a new one that skirted the ban: pure MDMA. While Nuwer says there is no record of who used this drug in the early 1970s, there is evidence of chemists producing it in Indiana, Chicago and New York.

Nuwer spoke to one retired literary agent, David Obst, who claims he took MDMA in the early 1970s before a pitch meeting with Simon & Schuster for the book All the President’s Men. The head of the publishing giant initially passed on Obst’s pitch, and the agent, feeling all the vibes, burst into uncontrollable tears. His emotions wore the publisher down, who finally gave him the green light. “So thanks to MDMA, we have All the President’s Men,” Obst quips in the book.

While experimental therapists quietly tested MDMA on patients experiencing extreme trauma and feelings of dissociation, it slowly became ubiquitous in clubs around the world. One of the first hotspots was the Starck Club, which operated in Dallas in the 1980s. “On opening night, someone flew down from New York and brought with him a suitcase full of ecstasy pills,” Nuwer said. “He told people to give MDMA out, and it just really popped off.”

The Starck Club became the center of a new kind of partying, which was less aggressive than spaces where the primary vice was alcohol or cocaine. That didn’t make it any less hedonistic. Nuwer describes it as “a scene that seemed to channel Sodom and Gomorrah” with a new wave soundtrack. Couples had sex on white couches near the dancefloor – and things got freakier inside the unisex bathrooms.

“You could buy [ecstasy] from the bartenders or the coat check girl, and it made the Starck Club a really special place where everyone was just loved up on ecstasy on the dancefloor, hugging it out. It was a place that welcomed anyone, regardless of race, orientation, gender or the way you looked,” Nuwer said. Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, Allen Ginsberg and Jean-Michel Basquiat all visited, not to mention future president George W Bush.

The man most responsible for keeping the party going was Michael Clegg, a seminary student turned drug kingpin.

Clegg tapped Carina Leveriza-Franz, an idealistic chemist who left her job at Intel, to make MDMA for his operation. After trying the drug herself and feeling a “heart opening”, Leveriza-Franz thought she was doing something good and spreading love in the world.

But as MDMA became the new club drug, it attracted the attention of Drug Enforcement Administration agents who arrested members of Clegg’s group. Agents busted Leveriza-Franz as she hid inside a blanket with her baby daughter.

“Leveriza-Franz ended up spending several years in federal prison for her role making MDMA, but she doesn’t regret her involvement,” Nuwer said. “She’s proud of what she did.” She now works as a hiking guide in Arizona. When Nuwer met her, she said: “I no longer need the molecule, I can impart connectivity and love without any drugs.”

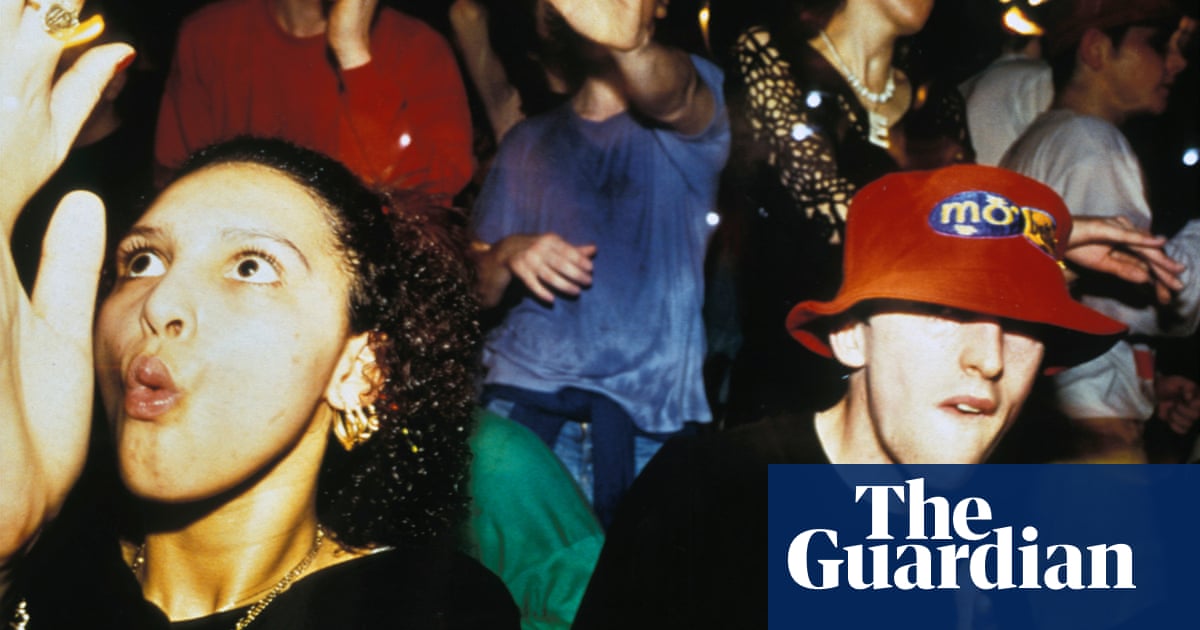

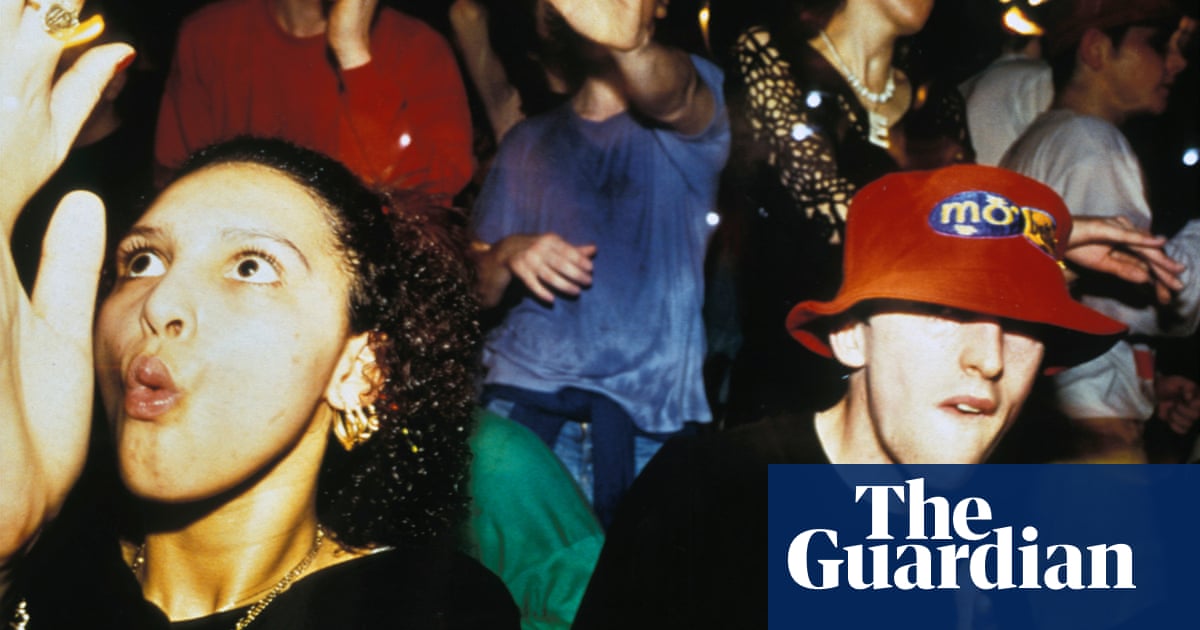

After MDMA hit the UK in the late 1980s, the press dubbed it the “second summer of love”. Underground raves, acid house music and smiley-face graphics fueled a new youth movement. “MDMA didn’t reform the UK, but it did change some social norms: men were hugging for the first time, or people from different socioeconomic stratospheres were partying together, instead of looking down on each other,” Nuwer said.

The 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act cracked down on unlicensed parties, spurring massive demonstrations and pushback.

It wasn’t all club kids using the drug. Nuwer’s book charts a few unlikely subcultures that used MDMA, starting with the Mormons. Even though the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints prohibits its members from drinking alcohol, a Mormon doctoral student told the drug activist Rick Doblin in 2003 that he’d personally taken MDMA more than 1,000 times. As he put it, molly was a common substance used by his friends in the faith.

“They were these Mormon kids who were otherwise straight-edgers going out to raves and partying all night,” Nuwer said. “I think they were doing some mental gymnastics to get around the rules, thinking it was fine to just try MDMA if they weren’t drinking.”

These Mormons became a key control group for MDMA researchers, Nuwer explains, as they could study the effects of the drug on them and know for certain they were not using any other substances.

Media depictions of rave culture might have centered on affluent white youth, but MDMA use has also become a part of rap music and culture. Khary Rigg, an associate professor of addiction research at the University of South Florida, started studying references to molly in hip-hop music by Jay-Z, Kanye West, Lil Wayne and others.

Most of the data Rigg found on MDMA exclusively covered its use by white people, but he wanted to find out what the drug meant to the Black community. So Rigg posted outside of clubs in south Florida, recruiting Black heterosexual MDMA users for his study. Eighty-two per cent of them said they tried the drug after listening to hip-hop songs.

“Whenever [rappers] mentioned [molly], they are either partying, drinking [alcohol], smoking [weed] or having sex,” one study participant told Rigg. “All of the things I love to do most. I never heard about anyone getting addicted or dying. That made me feel better about trying it.”

One of Nuwer’s most improbable sources: a man who disavowed white nationalism after trying MDMA. Brendan, whose last name was withheld, attended Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally and became the midwest coordinator for the neo-Nazi organization Identity Evropa.

After being doxed by an anti-fascist activist, Brendon lost his job, fell into a depression and applied to an MDMA study to earn some money. After trying the drug, Brendan told Nuwer he’d “fixated on stuff that doesn’t really matter, and is so fucked up … I hadn’t been soaking up the joy that life has to offer.”

Brendan hired a diversity, equity and inclusion consultant for himself and tried to distance himself from white nationalism. He reached out to the activist who doxed him and the two struck up an online friendship. Nuwer writes that similar stories of racists cured by MDMA, while rare, exist. One academic calls the drug a potential “pharmaceutical intervention” to hate.

No matter where they come from, Nuwer says all people who use MDMA have one thing in common: “They’re all doing it because they get something positive out of the experience.”

And that is what may finally shift public perception about MDMA therapy. A cottage industry of therapists and healers have used the drug on their clients for decades, and Nuwer’s book features some case studies: from veterans who have experienced war to adults grappling with childhood sexual abuse. These patients swear the drug helped them come back from their rock bottoms.

“MDMA lowers your defenses, so you can re-engage with your memories,” Nuwer said. “It reopens this malleable state in your brain, which scientists call a critical period, that helps you learn new skills and ways to cope.”

Nuwer says she uses MDMA about three or four times a year, strictly in a party setting. “I feel a bit shallow in my reasoning compared to the people I talked to for the book,” she said. But I Feel Love gives equal weight to the testimony of individuals who use the drug for any reason, whether it’s to address PTSD or simply have a good time.

Ravers may complain of the dreaded MDMA comedown – “the Tuesday blues” – when the drug’s jubilant high fades after it’s been metabolized by the body, and replaced by a crush of depression. Are those complaints exaggerated? “It’s never actually been scientifically proven that the comedown exists,” Nuwer said. “I do not doubt that, anecdotally, people experience this. What we do know is that people who take it in a therapeutic setting and clinical trials have not experienced that.”

Scientists hypothesize that MDMA alone does not make people feel terrible after they use it – rather, it’s what they mix with the drug.

While Nuwer knows that ecstasy is not a cure for all of society’s problems, she thinks many of her readers can agree that the world needs more of its byproduct: happiness and a sense of connection with others.

“MDMA reminds us that we’re all sort of here together, in this beautiful moment on this planet,” she said. “That in and of itself is worth celebrating.”