Singapore is due to execute a woman for the first time in almost 20 years on Friday, one of two killings planned for this week.

Singaporean national Saridewi Djamani was sentenced to the mandatory death penalty in 2018, after she was found guilty of possession of about 30g of heroin for the purposes of trafficking, according to the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), which tracks death row cases.

If it goes ahead, activists believe she would be the first woman to be executed in Singapore since 2004 when Yen May Woen, a 36-year-old hairdresser, was hanged for drug trafficking.

Mohd Aziz bin Hussain, a 56-year-old Singaporean Malay man, has been told he will be executed on Wednesday, according to the TJC. He was sentenced to death in 2018 after being found guilty of trafficking approximately 50g of heroin, the group said.

Singapore has some of the world’s harshest drug laws and has drawn international criticism in recent years for its executions of prisoners convicted of drug offences.

Saridewi is one of two women on death row in Singapore, according to Kirsten Han, a journalist and activist who has spent a decade campaigning against the death penalty. “Once she exhausted her appeal options it was a matter of time that she would be given an execution notice,” said Han.

“The authorities are not moved by the fact that most of the people on death row come from marginalised and vulnerable groups. The people who are on death row are those deemed dispensable by both the drug kingpins and the Singapore state. This is not something Singaporeans should be proud of.”

The government maintains the death penalty is an effective deterrent against drug-related crime, that it keeps the city state safe and is widely supported by the public. It also says its judicial processes are fair.

Research by Amnesty International found Singapore was one of a handful of countries that executed people for drug-related crimes last year, along with China, Saudi Arabia and Iran. Vietnam is also likely to have done so, it said, though the numbers of killings are not known.

“There is no evidence that the death penalty has a unique deterrent effect or that it has any impact on the use and availability of drugs,” said Chiara Sangiorgio, a death penalty expert at Amnesty. “As countries around the world do away with the death penalty and embrace drug policy reform, Singapore’s authorities are doing neither.”

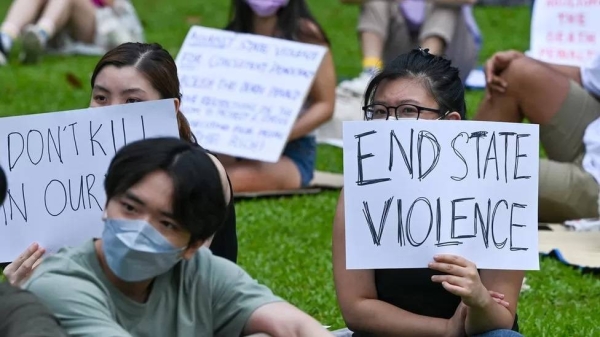

Activists in Singapore say it is the most vulnerable who end up on death row, and prisoners are increasingly representing themselves after their appeals because they cannot access lawyers.

According to TJC, Hussain had argued that most of his statements given to an investigating officer were not admissible because the officer had coerced him, promising him a reduced, non-capital punishment charge. The investigating officer disputed these claims, and the judge concluded that all the statements were given voluntarily.

TJC said Saridewi had argued that she had not been able to give accurate statements to the police because she had been suffering from drug withdrawal. The high court judge found Saridewi had “at most been suffering from mild to moderate methamphetamine withdrawal during the statement-taking period”, and that this had not impaired her ability to give statements, according to TJC.

At least 13 people have been hanged so far in Singapore since the government resumed executions after a two-year hiatus during the Covid-19 pandemic.