In 1983, Canning Town in the borough of Newham in east London returned the highest number of votes for the National Front in the country. A year later, the 16-year-old Black boy Eustace Pryce was murdered during a confrontation with racists in the area. By 1986 Newham registered the UK’s highest number of racist attacks. “It was a no-go area for Black people,” says Zak, then manager of London Weekend Radio (LWR). “People in cars would be shouting obscenities and calling you the N-word. It was a hostile environment.”

Despite this, between 1982 and 86, Black people from all across London drove to Canning Town in their thousands to dance all night in an underground sweatbox to soul, jazz-funk, rare groove, hip-hop and reggae. Bentley’s was a club in an old pub beneath an underpass. Unglamorous perhaps, but for those four years it became a bustling go-to destination. As part of Newham Heritage Month, the community interest company Rendezvous Projects has been digging into its influential history to produce a new booklet and podcast on the club.

“It was like our Paradise Garage,” says resident DJ Linden C, comparing it to the revered New York club. “It had a huge sound system in there that gave it this underground warehouse feel. Even though it had this bingo-looking carpet.” Opened by the white brothers Mark and Jack Homer with the intention of turning the old rock pub into a soul club, Bentley’s was unlike most other nightspots at the time in that it didn’t have a racist door policy that limited who could enter. “A lot of places didn’t want Black people in their clubs,” says Mark. “But I loved the music and could see an opening for good business.”

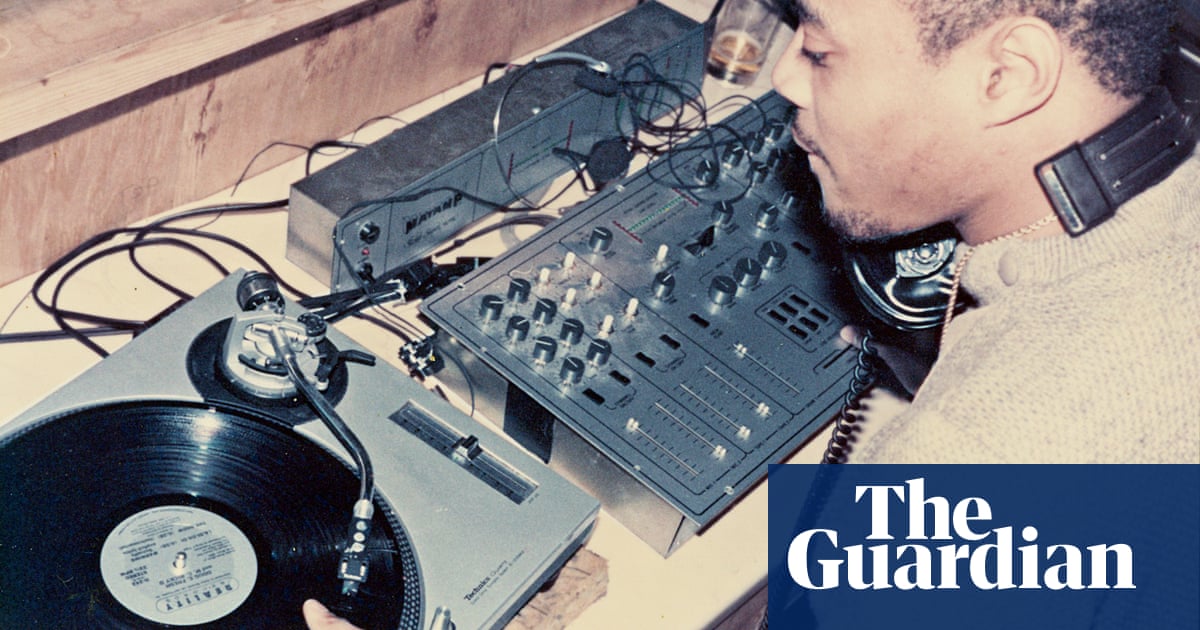

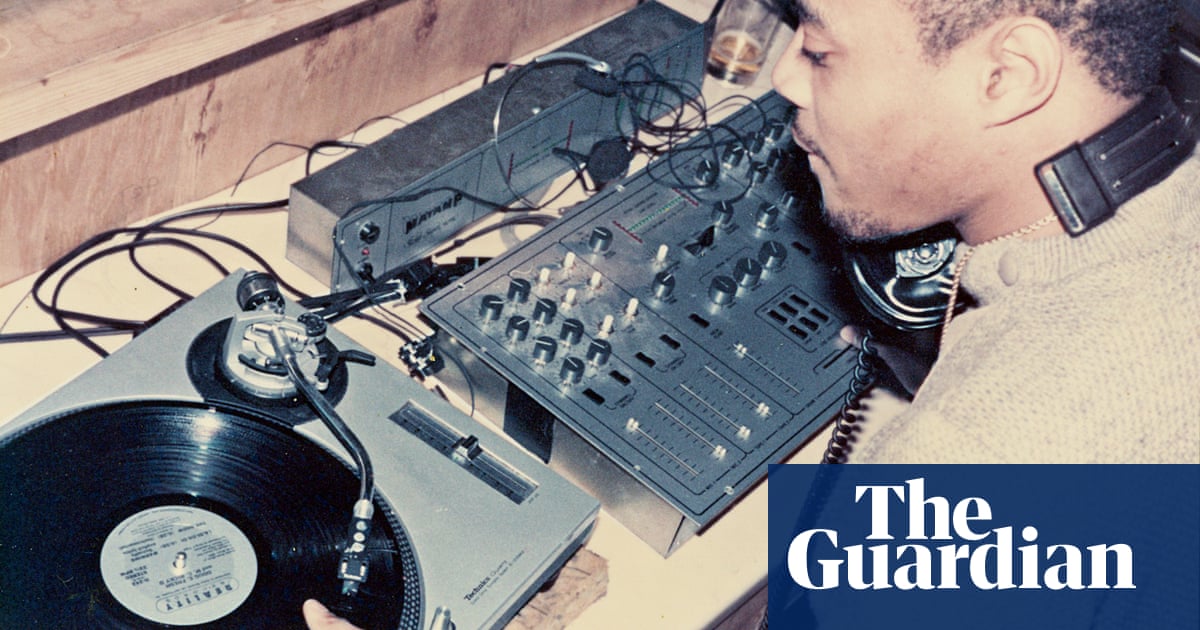

With Froggy as the resident DJ, Bentley’s soon built up an enviable roster, including C, Neil Charles and a supremely talented young guy called Derek B who ran a pumping Sunday party that would attract the likes of Norman Jay and Trevor Nelson. LWR had a live residency, pulling in performances from acts such as Five Star, Light of the World, Loose Ends, Jocelyn Brown and Edwin Starr.

Despite its tough surroundings, it was a place for people to sparkle. “It was like going to Ascot,” says DJ and presenter Elayne Smith. “You dressed special.” People would even clean their cars especially for it, resulting in a sea of glistening motors lining the streets. While the room could legally hold 600, it would often pack in double that, with thousands more regularly turning up. On the busiest occasions, the organisers emptied the car park and set up a stack of speakers to create an outdoor overflow dancefloor. “It was like a big family party,” says Homer. “My doorman’s mother-in-law would be upstairs making curried goat for everyone.”

Everyone recalls a mixed crowd that drew no troublemakers. “I didn’t see any racism,” says Smith. “What I saw was a movement of people that came together to party, meet one another and hear music. It was a real melting pot of cultures where music shouted louder than racism.”

LWR helped spread the Bentley’s gospel. When the station took up residency there in 1984, its reach was huge. “We knew from Department of Trade and Industry figures that we had listeners in the millions a week,” says Zak.

Smith was the breakfast presenter at the time. “Our direct competition was Capital and the Beeb,” she says. “But the advantage we had is that we had the streets.”

Linden C echoes this. “You’d walk down the street and hear LWR in every car, clothes shop, market and hairdresser,” he says. “It was instrumental in taking Bentley’s to the masses.”

During the LWR residency, the DJs played freshly imported records and organised live broadcasts that saw the club explode. “Our events caused roadblocks,” Zak says. “It was so gridlocked that the police had to ask us to help them clear the cars off the flyover and surrounding roads. It was like the whole of London had come to Bentley’s.”

However, the good times came to an abrupt end. On the 1986 August bank holiday weekend, more than 160 officers descended on the club in the largest police raid in Newham’s history and shut it down with immediate effect. “The raid was terrifying,” says Homer. “An articulated lorry pulled up and all the police jumped out the back with guns. They came flying in like lunatics – completely over the top”.

The police were responding to a tipoff that the club was being used for firearms storage. No guns were found but some cannabis and knives were seized. The Newham Monitoring Project criticised the police action as heavy-handed and as a provocative gesture towards Black people. At the time, Scotland Yard said such criticisms didn’t merit a response.

Today, Homer bluntly describes the motivations as racist, and suggests that the previous year’s Broadwater Farm riot was still fresh in police minds. “You had 1,000 Black people there and they thought: ‘If this kicks off, we’re fucked,’” he says. Homer also wonders whether, given that they were located in an area ripe for development, they were seen as standing in the way of progress. “It was in an up-and-coming area of the docklands, and who wants a Black club there?” he adds.

Zak feels similarly. “There was never any trouble there,” he says. “It was just: this club has Black people in attendance and we don’t want that.”

It was a sour and “heartbreaking” end for Homer, who felt too downbeat to risk starting it up again. With the legacy and longevity of fellow pirate radio station Kiss FM eventually outweighing LWR, along with narrow retellings of club history often excluding Black stories while heavily framing the late 1980s as a ground zero, Bentley’s has until now remained absent from much of the documented history of UK club culture. Nevertheless, it remains a special place for those who were in its grip. “Bentley’s was a breakthrough,” says Zak. “It was so harmonious. It was just beautiful to behold.”

The All Roads Lead to Bentley’s limited edition booklet and podcast can be accessed here