Since the Conservatives narrowly won a shock byelection victory by campaigning against a key low-emissions zone known as Ulez in London, there have been seven days of turmoil for climate policy in the UK.

Support for a net zero UK by 2050 is expressed among all ages and types of political voter, according to the pollsters. But nevertheless, Rishi Sunak’s government scented in Uxbridge a possible “wedge” issue that could put Tories on the side of swing voters and pit them against Labour.

Almost immediately, senior cabinet ministers began to flirt with the idea of watering down some climate policies that the public might regard as too costly to them personally in the short term.

In the firing line? The ban on petrol and diesel cars by 2030, phasing out gas boilers by 2035, energy efficiency targets for landlords and low traffic measures.

Tory insiders say Sunak is committed to renewables and decarbonising the energy sector but that he appears to be more sceptical of the car and boiler targets brought in by Boris Johnson, which they say the former prime minister brought forward without much thought for the consequences or feasibility.

Alongside this, there is the temptation among senior Conservatives to cast Labour as going too far in support of green measures that will cost voters money, tapping into fears about the party’s stewardship of the economy that Keir Starmer and the shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, have worked relentlessly to dispel.

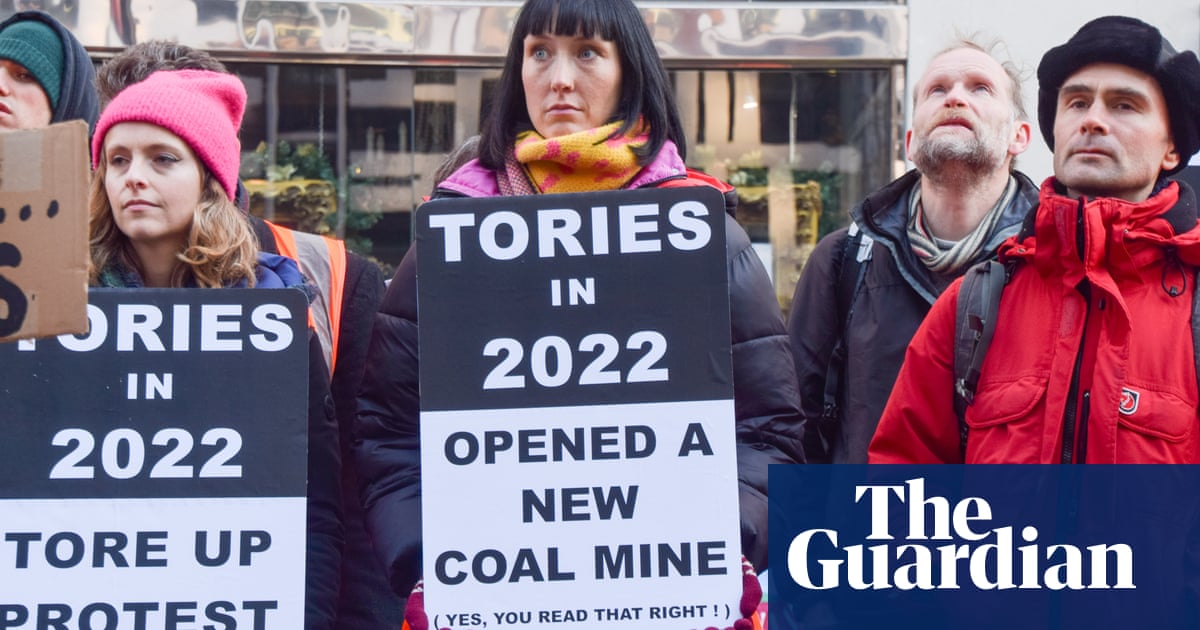

Grant Shapps, the energy secretary, has led the charge, accusing Labour of supporting a “criminal eco mob” of climate protesters, and recording a video slamming the party’s policy of no more oil and gas drilling in the North Sea.

“It is playing with fire; we undermine the political consensus on net zero at our peril,” says one Conservative MP who strongly supports tackling the climate emergency but was reluctant to stick his head above the parapet to say so publicly. “We also need to remember that voters are heavily in favour of our net zero targets.”

Sebastian Payne, director of the centre-right Onward thinktank, who has warned that scrapping the net zero agenda could cost the Conservative party 1.3m votes, said the party had always had to strike a “balance between conservation and growth”.

“We do believe very strongly that net zero and renewables are critical for the country and economy’s future and we shouldn’t resile from it,” he said. “On the politics, if you look at how many MPs are members of the Conservative Environment Network versus how many are on the Net Zero Scrutiny Group, I think that tells you where the centre of the party is on the environment.”

Conservative MPs who back measures to tackle the climate emergency are far more numerous than sceptics, with more than 130 parliamentary members of the party’s environment network. Chris Skidmore, the leading Tory voice calling for more net zero support, said this week that abandoning climate policies would be “an abdication of responsible government”, and he is considering launching a Westminster “climate charter” to galvanise backing for its aims.

Zac Goldsmith, the Tory peer and ally of Johnson who resigned with a devastating criticism of the government’s commitment to protecting the environment, also weighed in with a Guardian interview specifically singling out Michael Gove and Shapps for backsliding on their support for net zero.

However, some of the net zero sceptics are noisier. A stream of rightwing Conservatives from Jacob Rees-Mogg to David Frost jumped on the first signs of a cracking in the political consensus to claim that it was more pragmatic and could win the party more support.

Iain Duncan Smith, the former Conservative leader and cabinet minister, was one of those making the argument that the UK has set itself too stretching targets compared with other countries internationally, particularly on the 2030 ban on new petrol and diesel car sales.

“We’re having to subsidise a switch to green technologies and the key point is how quickly we can do all of this because it feels to me like 2030 was just plucked out of the air. There’s no question that the British car industry will not make 2030 in a competitive shape on this if you demand that they drop petrol and diesel cars by then.”

Right-leaning newspapers also jumped on the bandwagon with leaders calling for a delay to the nearer term targets. And by the end of the week, talk of a U-turn on climate policy had reached the New York Times, which ran a piece on the British Conservatives’ commitment to green issues being tested.

Jill Rutter, a senior fellow at the Institute for Government, said Whitehall and business would be worrying about the mixed messages.

“This isn’t the first time government has flip-flopped on climate policy. There has been an awful lot of on-off-ing particularly from the Treasury including when Rishi Sunak was chancellor – on carbon capture, and the green homes grant,” she said. “If you are someone working on this you would be looking at it with a degree of despair.”

At first glance, it has looked this week as though the Tories’ splits on green issues could be mirrored in the Labour party. In the hours after last week’s Uxbridge byelection result, more than one ally of Keir Starmer was taking the shadow net zero secretary Ed Miliband’s name in vain.

While the Labour leader blamed the expansion of Sadiq Khan’s clean air zone for his party failing by just 495 votes to take Uxbridge and South Ruislip from the Tories, others felt it spoke to a wider electoral vulnerability.

One party source said: “It shows that our focus on the green agenda could backfire. We need to be careful that it doesn’t leave us open to Tory attacks or let it distract from our core messages.”

Another added: “We need to talk about the economic challenge rather than net zero. That’s the public’s overwhelming priority”.

Miliband, however, dismissed the noises in the wake of the byelection as “tittle tattle”, telling BBC Radio 4 that he was “far too experienced to be worried about that kind of thing”.

He went on: “The truth is that Keir Starmer is absolutely 100% committed to the project of clean energy by 2030, which is the way to cut bills and give us energy security and tackle the climate crisis”.

Senior Labour figures stress that for the past 18 months, Miliband has been talking about the green agenda through the prism of the cost of living crisis. “It is possible to do both,” they say.

But others in the party have been spooked by Starmer immediately laying the blame for the failure to take Boris Johnson’s old seat on the London mayor’s Ulez policy.

At Labour’s National Policy Forum (NPF) in Nottingham the following day, Starmer told his party: “We are doing something very wrong if policies put forward by the Labour party end up on each and every Tory leaflet.”

His allies deny that his approach to Ulez should be interpreted as him backing off his climate commitments, suggesting the nuance was lost as “politics is a primary colours business”.

Senior Labour figures insist that “nothing has changed” in the past week – despite appearances – and that Starmer and Reeves remain “firmly committed” to the green agenda.

They point out that at the NPF the party formally signed off on bold commitments on clean power by 2030, setting up Great British Energy and not granting new oil and gas licences in the North Sea.

“The real change on this has been in the Conservative party,” one said. “Shapps and Sunak are obviously desperate and have decided they want to have a bit of a culture war on these issues. I don’t think it’s going to work.”