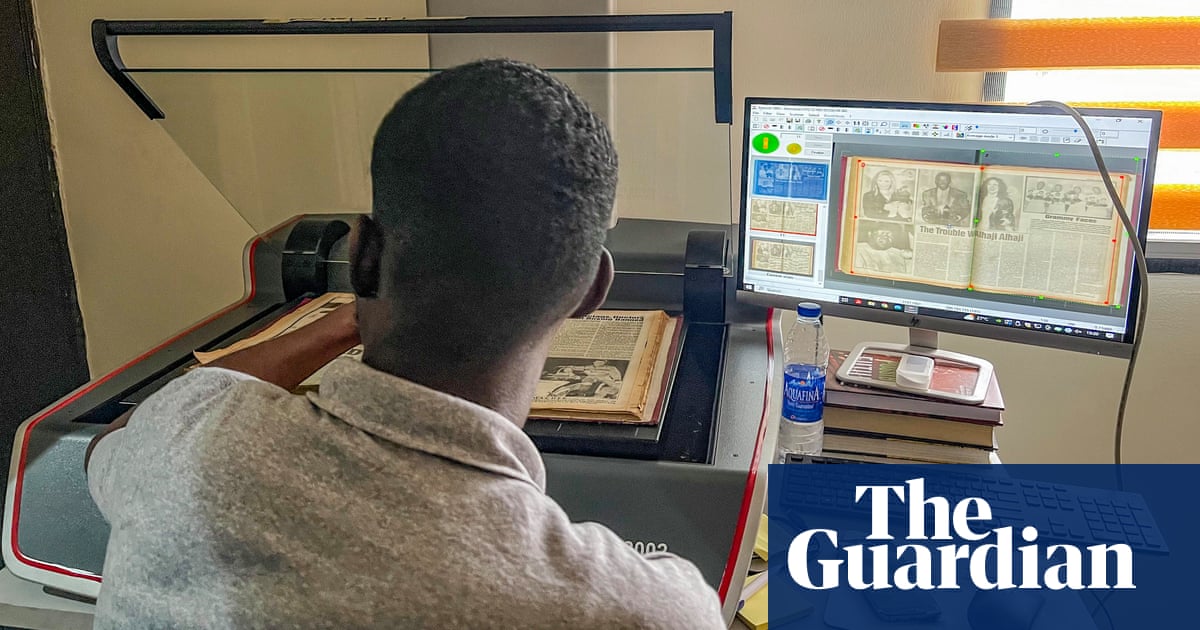

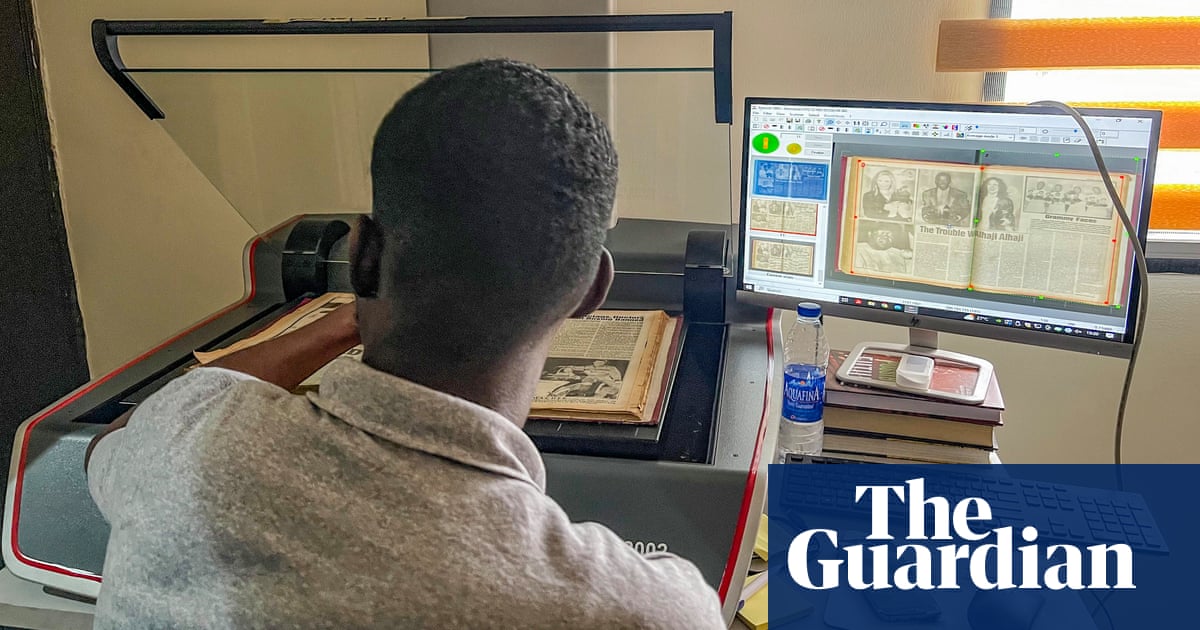

In a quiet office in Lekki, an affluent suburb of Lagos, Nigeria, Boyega Adediran gingerly opens a 1997 copy of PM News and places a double-page spread on a large flatbed scanner. The newspaper was founded in 1994 but stopped printing physical copies in 2015.

Scans of the fragile pages are quality checked by Grace Abraham and saved to a server that currently holds more than 50,000 pages of what will become Nigeria’s first interactive digital newspaper archive.

A nonprofit startup called Archivi.ng is attempting to digitise every edition of every newspaper – 50 in all – published in Nigeria since 1 January 1960, the year of independence from Britain.

The archive will launch its first tranche of documents in September. Dozens of volunteers have already spent months scouring libraries and meeting with publishers to get copies of old papers.

“Nigerian history is inaccessible online, and the greatest repository of that history is old newspapers,” says Fu’ad Lawal, the founder of Archivi.ng. “The newspapers from our history are rotting away in libraries and private archives, and our mission is to stop the erasure and recapture all the history before we lose them for ever.”

Allegra Ayida, a Nigerian doctoral researcher in history at Yale University who hopes to use the archive when it launches, says: “This exciting project fills an important gap in both accessibility and centralisation of a large volume of information.”

“The potential of having a newspaper archive since independence would allow the tracing of Nigerian history across 60 years in a country that has had 15 different leaders, five military coups, a bitter civil war, an annulled election, an interim administration and a brutal dictatorship,” she says.

Since independence, history has been removed then reintroduced to the school curriculum, depending on who was in power in Nigeria’s revolving door of military dictatorships before democracy was restored in 1999.

In 2009, under President Yar’Adua, history was removed from the curriculum, ostensibly because there were not enough teachers. Last year, the then president, Muhammadu Buhari, made the subject compulsory again.

Lawal has been surprised by the level of detail printed about the military coups and how much resistance there was among editors. Newspaper offices would often be raided or shut down by the government, and journalists faced intimidation, arrest and even death. One celebrated journalist, Dele Giwa, was killed by a parcel bomb in 1986 during Ibrahim Babangida’s presidency.

“The biggest discovery is not a single story. It is a series of events, the zeitgeist,” Lawal says. “We know so little about the amount of resistance that the military government met. So when Nigerians say, ‘We need someone with strong hands’, I say we don’t. The best thing that has happened to us is democracy. There is so much we don’t know about the fine details of those times, and how they shaped our present.”

Lawal believes a lack of publicly accessible historical data contributed to Buhari’s return to power in 2015. He previously ruled between 1983 and 1985 following a military coup.

“Without documentation, we have false nostalgia because if you looked at Buhari’s eight years [in his second term], it’s like entering a deep cryogenic sleep in 1985 and waking up in 2015. He just continued where he stopped in terms of policies and governance,” says Lawal.

Archivi.ng raised $15,000 in public donations for the archive, but needs $100,000 to complete the project.

The biggest challenge, however, is navigating Nigeria’s intellectual property law, which classifies newspapers as “literary works”, meaning reproduction of any kind needs the publishers’ permission. According to Lawal, some have been reluctant to help.

“We are doing the infrastructural work, we are digging the well [of information] for people to come and fetch,” he says.