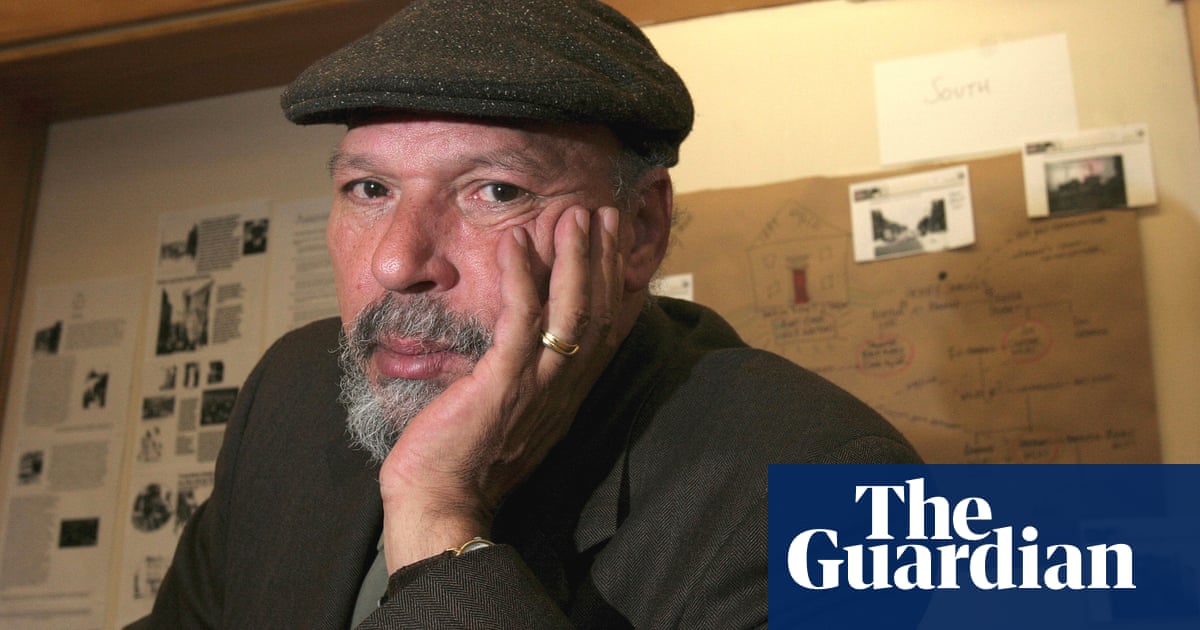

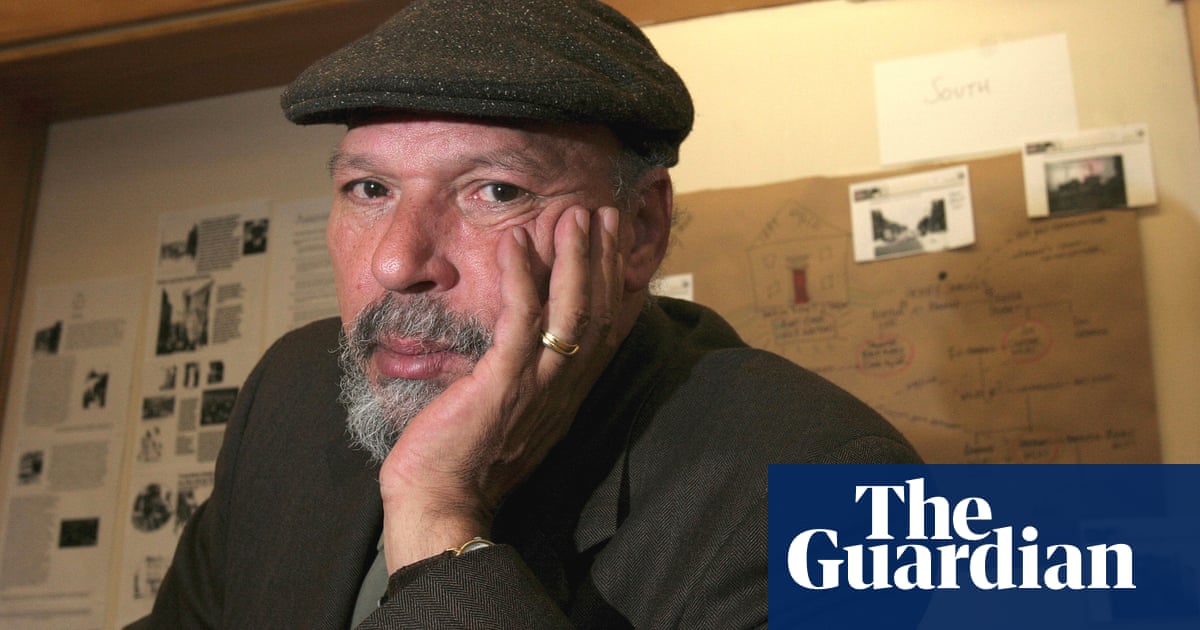

The host was Bill Moyers, former White House press secretary under Lyndon Johnson. The guest was August Wilson, one of the great playwrights of the 20th century and unofficial laureate of African American history and culture. It did not go well.

“Don’t you grow weary of thinking Black, writing Black, being asked questions about Blacks?” Moyers asked on his PBS show A World of Ideas in 1988.

Wilson replied with a question of his own: “How could one grow weary of that? Whites don’t get tired of thinking white or being who they are. I’m just who I am. You never transcend who you are. Black is not limiting. There’s no idea in the world that is not contained by Black life. I could write forever about the Black experience in America.”

It is a pity that Wilson, who died in 2005, is not around to offer his views on current debates around representation. He criticised the idea of colorblind casting, arguing that an all-Black Death of a Salesman was irrelevant because the play was “conceived for white actors as an investigation of the specifics of white culture”.

He insisted to Hollywood that any film adaptation of his best known play, Fences, must have a Black director (“White directors are not qualified for the job. The job requires someone who shares the specifics of the culture of black Americans”). Fences eventually became a movie in 2016, directed by Denzel Washington.

And Wilson’s own work – epic and lyrical, vividly centring marginal figures such as taxi drivers and rubbish collectors – has been challenged for its relative lack of strong women.

There is some irony, then, that the first major biography of Wilson is written by a white woman. Patti Hartigan, a former theatre critic for the Boston Globe newspaper who knew Wilson personally, publishes August Wilson: A Life later this month. She knows the subject of race will come up everywhere she goes to promote it.

Hartigan says by phone: “In terms of writing this book, it’s 2023; he died in 2005. He’s possibly the most important American playwright of the latter part of the 20th century and there’s no biography. I don’t even want to count the number of people who have passed since I started the research on this book. I had to get to them while they were around and I think the work stands for itself.

“As a white female, I’m extremely sensitive and extremely careful and it makes you work harder to tell the story right. Jonathan Eig [who is white] said that about his Martin Luther King biography: you check every word, you think about everything, you have 12 people read it.”

She notes that police brutality and racial injustice, culminating in the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, would have come as less of a shock to Wilson than it did to many Americans. “This was no secret to August Wilson and all of his friends and peers in Pittsburgh and St Paul and Seattle in the theatre world.

“It’s only because a young woman took a video and it was a pandemic and people actually saw that they started to pay attention. All of the things that were said about George Floyd are in plays that he wrote 30 or 40 years ago. It was an awakening in the dominant culture.”

Wilson is celebrated for his 10 plays (known as the “Century Cycle”) about African American life, nine in Pittsburgh and one in Chicago, each set in a different decade of the 20th century. When Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom premiered on Broadway, New York Times critic Frank Rich wrote that Wilson “sends the entire history of black America crashing down upon our heads”.

He won two Pulitzer prizes – for Fences in 1987 and The Piano Lesson in 1990. He turned down dozens of screenwriting offers including Steven Spielberg’s 1997 film Amistad.

Wilson said he did not research his plays but wrote from “the blood’s memory” of the Black experience going back to slavery. He wrote in longhand, often worked until 3am and did not recognise writer’s block. He drank copious amounts of coffee, smoked five packets of cigarettes a day (he was once spotted emerging from a shower with cigarette in hand) and never learned to drive.

Hartigan was fresh out of university, a young critic writing for small weekly paper, when she first met Wilson in 1987. She told him that she had seen his play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at the Huntington Theatre in Boston. He asked if she had seen Fences on Broadway. She blurted out, “My mother saw it, but I can’t afford a ticket,” and then instantly thought, how could anybody be so young and stupid to say that?

But the next day she received a note saying two tickets were waiting for her at the 46th Street Theatre in New York for that Sunday’s matinee of Fences. “So I got to see James Earl Jones on Broadway!” she recalls.

Hartigan would get to know Wilson and interview him often. She profiled him for the Boston Globe’s magazine in 2005. With obvious warmth, she recalls him as a raconteur with a generous spirit. “At an opening night party for him he would prefer to be in the corner talking to the waitstaff than being with the boldface names,” she says. “But as he got more and more famous he had to go to the galas and he had to be the guy in the suit with the Borsalino fedora.

“But he was a gifted storyteller. He could sit down and hours would pass and you wouldn’t even know. He told the same stories over and over again, but you felt as if you were hearing them for the first time. If you were interviewing him, you would walk away thinking, ‘I’m the best interviewer in the world!’ Because all he did was talk and tell you these fabulous stories, with these great punchlines and lessons. But he really told the same stories over and over.”

She adds: “A lot of writers are like this. We are introverts who, when called upon, can be extroverted. In his heart he was shy but he was great at talking to people.”

Hartigan’s biography traces Wilson’s family history back to slavery and finds striking parallels between his ancestors’ stories and the plays. He was born Frederick August Kittel in Pittsburgh in 1945, the son of Daisy Wilson, a Black woman who cleaned homes, and Frederick August Kittel Sr, a white German baker 24 years her senior and already married.

“Freddy”, as his mother nicknamed him, and his siblings grew up in a modest home without hot water, and saw little of their father. He worshipped his mother, changed his name to August Wilson and always identified as Black. At a young age he noticed that cashiers at a Woolworth’s store gave papers bags to white but not to Black customers to carry their purchases. As an adult, he would ask for a paper bag, even if only buying a packet of gum.

Hartigan writes: “Later in his life, he would bristle when grilled about being biracial. Colleagues in the professional theater community, both Black and white, whispered behind his back about his heritage, but he never wavered from his self-definition as a Black man. Unlike his uncle Ray, he never considered passing. He was raised by Daisy in the Black community, and he was Black, period.

“But the people who snickered at his poetry reading saw something different. They saw a light-skinned tweedy chap with a grandiose accent and a slight stutter reading verse that didn’t speak to them. No matter how Wilson viewed himself, his contemporaries acknowledged that he appeared different from the regulars at the Halfway Art Gallery, many of whom had adopted African names and proudly wore dashikis and kufi caps.

“‘August wasn’t really Black. He was half-and-half,’ [Pittsburgh poet] Chawley Williams said. ‘He was too dark to be white, and he was too white to be dark. He was in no-man’s-land. I knew he was lost. I was lost. Kindred brothers know one another. We were trying to become men. We didn’t even know what it meant.’”

Wilson was a precocious child and learned to read at four. But he repeatedly dropped out of high school for reasons including racism and being wrongly accused by a teacher of plagiarism in an essay about Napoleon. He feasted on books at the local library while befriending street artists and poets.

The vibrant, multicultural community of Pittsburgh’s Hill District was a profound influence and finds expression in vernacular speech and richly drawn characters such as Hambone, a man with an intellectual disability in the play Two Trains Running, and Aunt Esther, a recurring character in the cycle said to have lived for more than three centuries. Wilson’s old home, derelict at the time of his death, has undergone initial restoration with ambitions to become an arts centre. The August Wilson African American Cultural Center in downtown Pittsburgh has a dedicated exhibition with 13 separate walk-through installations – 10 of which focus on the plays in the Century Cycle.

Hartigan says by phone: “This city was in his blood. But you love the place that formed you but you can’t go home again. He had a love-hate relationship with the city.

“When I was interviewing in 2005 he said that when he had written Two Trains Running, there was a Swedish film crew doing a piece on him and they went to Pittsburgh and they went all over the Hill asking if they could film Hambone, and it got him mad because they felt he couldn’t have made that up. He did make it up. All of them were the composite of all the different people he met over the years in Pittsburgh.”

Wilson, who moved to St Paul in 1978 and Seattle in 1994, broke racial barriers in American regional theatre. White audiences would tell his most important director, Lloyd Richards, that they felt it was the first time they had been invited into a Black person’s home. But progress was glacial. At the end of his life, Wilson saw that the overwhelming majority of theatres were still run by white people.

In an interview with TV host Charlie Rose in 2005, he reflected: “When I go to these theatres … I count 33 people who work at that theatre, you know, carpenters, electricians, whoever, people working in the press office, they’re all white. They’re simply all white, everywhere you go. Security guards are all Black. I’ve never seen a white security guard in any of these theatres.”

Wilson married three times, had two daughters and generally put work before family (his second daughter called him “the slippery guy”). He was just 60 when liver cancer cut him off in his artistic prime. He was planning a new play, tentatively called The Coffin Maker Play, and had started work on a novel and had ambitions in cinema.

Hartigan says: “He wanted to write things that weren’t necessarily about the Black experience in the 20th century. He had so much more in him. He certainly had a great deal of satisfaction that he finished the 10 plays. He was hoping it was going to free him up to do other things and he never got the chance. Wouldn’t you love to read that novel?”

Wilson’s status as the American Chekhov only strengthens with time. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was turned into a film by Netflix starring Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman in 2020. The Piano Lesson was revived on Broadway last year with Samuel L Jackson, John David Washington and Danielle Brooks (a big-screen adaptation is also on the way). A prop from that show – a piano with the impression of ornate carvings – was donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. Hartigan’s book aims to further cement the augustness of August Wilson.

“I hope to introduce him to people who aren’t familiar with his life story and his work,” she says. “I want this to be a legacy biography, where he will be remembered for his brilliance and his contributions. But also it’s the quintessential American story in a way that the majority culture doesn’t think of it. He came from nothing and he did extraordinary things in a way-too-short lifetime, and it counts as one of the great American stories.”

August Wilson: A Life is out now