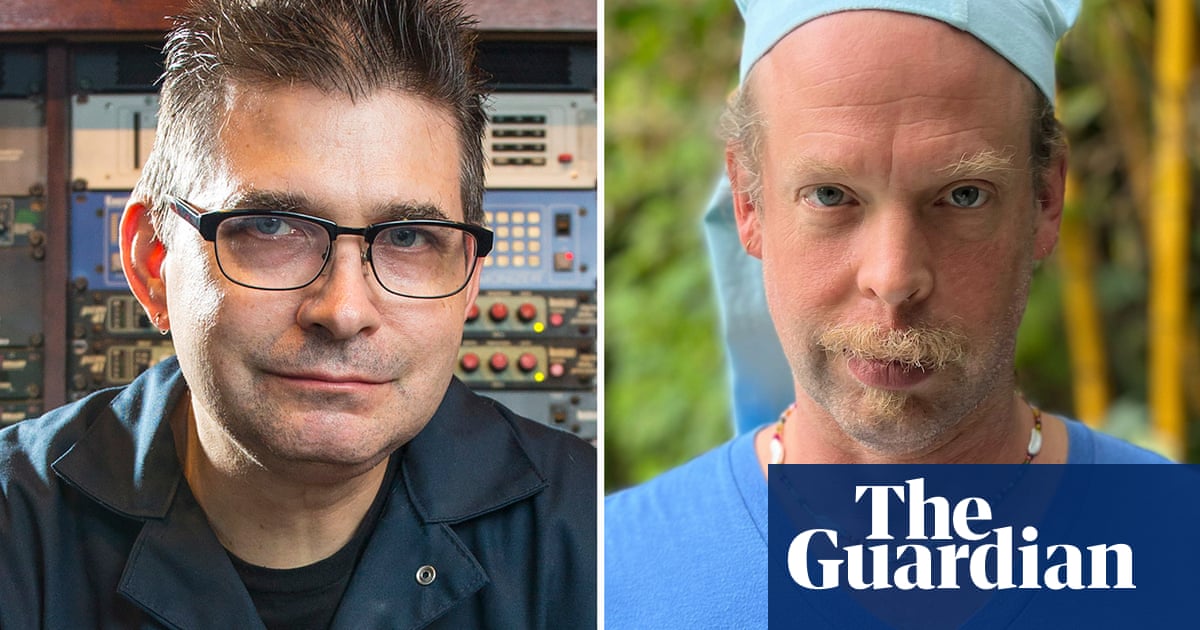

The musician Steve Albini and I had been chatting for about a half hour, going over the particulars of his daily routine, the financial viability of his business, and various other prosaic and uncontroversial subjects, when it suddenly seemed appropriate to ask about the decades-long stretch of time where he’d sort of seemed like a giant asshole. Several months before, on Twitter, he’d felt moved to explain some of the terrible things he’d said in public over the years. This might not seem so remarkable: many people – the famous, the semi-famous, the completely insignificant – have spent a lot of time apologising on Twitter for their former selves. But when Albini decided to acknowledge his past in direct terms, with no qualification or defensiveness – “A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them” went one line in what became a viral thread – it engendered a somewhat astonished reaction along the lines of: “Damn, if Steve Albini is saying this, then nobody else has an excuse.”

Possibly you are wondering why it matters that Albini – from afar merely a middle-aged American musician who tweets a lot about poker and US politics – was re-evaluating his past. He’s never written a hit single or performed on a late-night television show or sung a melody that could be described as catchy. His most famous song, Kerosene, is a six-minute case for the recreational merits of arson. But his significance vastly outweighs his fame. Even today, the mention of his name conjures a complete worldview that, years after its peak, still inspires deep respect and occasional controversy. Albini – and I can’t say this without it sounding a little silly because of the way the music industry has conspired for decades to sand off the edges of any once-transgressive cultural movement, but more on that later – is a genuine punk rocker. Not because he plays music with distorted guitars or exudes contempt for pretentious establishment figures – though he has done plenty of that – but because throughout his career he, perhaps more than anyone else, has attempted to embody the righteous ideological tenets that once made punk rock feel like a true alternative to the tired mainstream.

Albini launched his career in the early 1980s as the leader of Big Black, a band whose pummelling sound and searing visions of small-town evil made them heroes to record store clerks and nerds with aggression to burn. Big Black embodied the DIY spirit: they booked their own tours, never signed a contract, never hired a manager, never even considered joining a major label and broke up at the height of their “fame” (a very relative term in this scene). When Albini transitioned into his second career as a recording engineer in the late 1980s, working on era-defining albums by the Pixies, PJ Harvey and Nirvana, the music he produced echoed his old band’s principles. Albini was especially good at capturing the raw sound of a band, as though they were playing right in front of you. Over time, hiring Albini became a way for artists to signal their interest in sounding “realer” – and beyond that, in seeming more honest and pure, especially if they were making their album on a major label. “To me he was the king of the underground,” says Gavin Rossdale, frontman of Bush, whose 1996 album Razorblade Suitcase was produced by Albini.

So there was the music, much of which was exceptionally good. But Albini also stood out for acting like the biggest jerk in a milieu that was not exactly inhospitable to jerks. In his public capacity as “Steve Albini”, he often came off like the resident wiseass who thinks he’s smarter than everyone else and thus spends his time getting a rise out of anyone who isn’t clever enough to get the joke.

Let’s recap some of the statements and actions that gave Albini his reputation. Rude as hell: “Three Pandering Sluts and Their Music-Press Stooge” – a 1994 letter he wrote to Chicago Reader music critic Bill Wyman in which he ripped into local artists Liz Phair (“a fucking chore to listen to”), Smashing Pumpkins (“ultimately insignificant”) and Urge Overkill (“Weiners in suits playing frat party rock”) and signed off with “Fuck you”. Outright uncomfortable: during performances of Jordan, Minnesota, a Big Black song about a (later disproved) child-sex ring in the town of that name, Albini would sometimes pretend he was one of the children being raped. Completely indefensible, both then and now: his extremely short-lived band Run N****r Run (the poster line from a 1970s blaxploitation film called The Black Connection, which he says his then-roommate was obsessed with), and their 1985 single Pray I Don’t Kill You Faggot, about which he said to me: “I’m embarrassed by it, and I don’t expect any grace from anybody about that.”

I could go on – there are a thousand more instances of this type of thing from across the years, all of which led to an uncomfortable question: what might it mean if the most principled practitioner of the venerated punk ethos was a thoughtless provocateur at best, a hypocritical bigot at worst?

Kim Deal of the Pixies and the Breeders is a close friend of Albini’s. She told me how she’d recently revisited an article Albini wrote in 1991 for the independent music magazine Forced Exposure in which he savaged various bands he’d worked with, saying things like “Never have I seen four cows more anxious to be led around by their nose rings” (about the Pixies) and “They had a really fruity drummer for a while, but I think he died of the syph” (about the Illinois rock band Poster Children). “It’s pretty horrible what he was saying,” Deal said. “I look at it and just go: Oh my God, what is this guy doing?”

So when Albini expressed public contrition in late 2021, it surprised a lot of people who mostly remembered him as an incendiary jerkoff and assumed that he – like many public figures who are pushed to admit wrongdoing – would rather chalk all of that up to “well, it was a long time ago”. But those who knew him intimately were less bewildered. Over the years, they had observed the slow evolution of Steve Albini, as he shed some of his abrasive and adversarial habits while holding fast to the sturdy principles that have always anchored him. He has not exactly become mild-mannered with age – “However you define ‘woke,’ anti-woke means being a cunt who wants to indulge bigots,” he wrote recently – but these days he also says things like: “Life is hard on everybody and there’s no excuse for making it harder. I’ve got the easiest job on earth, I’m a straight white dude, fuck me if I can’t make space for everybody else.”

When I spoke to the folk singer Nina Nastasia, who has made every one of her records with Albini, she called him a “gentleman”. Joanna Newsom has described him as “a pure joy to work with”. Kim Deal told me: “I could just break into tears, the human he’s become.” These are not sentiments typically associated with an individual who once called Courtney Love a “psycho hose-beast” in print and told an interviewer from GQ: “I hope GQ as a magazine fails.” How did this happen?

Ifirst met Albini in Chicago last summer, at an outdoor cafe filled with dogs and babies. After pulling up in a well-used Ford hybrid, he greeted me wearing two face masks, one white and one black. (The week we met, two bands he was scheduled to work with had to cancel their sessions because a member tested positive for Covid.) In the course of the many hours we spent together over the next week, I saw the lower half of his face maybe half a dozen times – only when he lowered both of his masks to sip his drink – preventing me from adding the usual journalistic flourishes like “he said, his mouth crinkling into a small smile”. Which would have felt kind of stupid anyways, because he talked about music and everything else with an unsentimental efficiency that echoed his ability, in his own bands, to condense profoundly combative and confrontational attitudes into just a few lines or riffs.

Albini’s speaking voice is a pleasant, even-keel murmur made for podcasts and instructional videos. He is not a hippy, but his meticulousness in sketching out his interior life without seeming defensive or grandiloquent suggests a knowledge of self that billionaires pay to discover on ayahuasca retreats. The facts of his life are straightforward: he was born in 1962 in Pasadena, California. After moving around a lot, owing to his father Frank’s work as a wildfire research scientist, his family eventually settled in Missoula, Montana, where Albini lived what he called a “normal Montana childhood” – mountains, trees, things of that nature – until, as a teenager, he was introduced to the first Ramones record. Imagine what it was like, decades before a CBGB-themed bar was installed at Newark airport, for a nerdy kid living in a cultural vacuum to come across these flippant shit-stirrers and their catchy, unpretentious music. “It was the first time I felt like there was any part of culture that represented the irreverence and goofiness and kind of mania that my friends and I were displaying,” he recalled.

After graduating from high school, Albini left Missoula for Evanston, Illinois, where he enrolled in Northwestern University’s journalism programme and gravitated towards the nascent punk scene in nearby Chicago, where he ended up staying for the rest of his life. Albini would attend concerts that today inspire envy in underground music fans: a double bill of Hüsker Dü and the Replacements for $3; single-digit crowds for the Wipers and Bauhaus; weekly gigs by formative Chicago punk bands the Effigies and Naked Raygun.

While he was still at Northwestern, he started Big Black. Their 1982 debut EP was played entirely by Albini, with the help of a drum machine, and sketched what would become recurring themes: a distrust of authority, a comfort with violence, a fascination with society’s depraved and unwanted. But it was after Albini recruited the bassist Jeff Pezzati and the guitarist Santiago Durango, both of Naked Raygun, that the band found its identity. (The drummer would remain a programmed Roland TR-606 drum machine, affectionately referred to as “Roland”.) Their next release, 1983’s EP Bulldozer, was a quantum leap. The guitars buzzed and revved like heavy machinery on the factory floor; the rhythm section was now driving the music rather than just keeping time; Albini’s voice, mean and biting, retained a ringmaster’s control over the serrated noise. It is pissed off, antisocial music that puts one in the mood to demolish a jock’s car with a baseball bat. Although the band was no longer a solo project, Albini exercised minute control. “I didn’t have to book any shows. I didn’t think of any songs,” said Pezzati, whose bass parts were dictated in the studio. “He wanted the songs to sound like he wanted them to sound.”

In the US, the 1980s independent music world arose out of scenes like the one in Chicago. Bands would then slowly pollinate across the country through college radio stations, packed touring itineraries, old-fashioned word of mouth and coverage in zines – the small but passionate publications that covered below-the-radar artists and all their dramas. One ideological dividing line among these acts was a band’s interest in signing with a major label. Some bands moved up and became very prosperous (REM, Sonic Youth); some bands moved up and did not (the Replacements, Hüsker Dü); some bands stayed right where they were and were more venerated because they held true to their indie ideals. Or as Santiago Durango put it to me: “Big Black really confirmed for me that I would never be in a band that was commercially successful.”

Big Black’s music was appreciated for its mulish intensity, and Albini’s willingness to talk shit, in an ecosystem where shit-talking was seen as a sign of obstinate authenticity, gave them enhanced status. One weapon of choice was the writing he did for the 80s zine Matter, where he mercilessly critiqued his peers (“This is a sad, pathetic end to a long downhill slide,” he wrote of the Replacements’ now-classic album Let It Be) and feuded with local acts and venues he deemed ethically or artistically lacking. “We weren’t particularly well-liked in Chicago,” Albini admitted.

Along with these aesthetic provocations, Albini would, in writing and interviews, habitually use offensive language in a way that seemed to be unadulterated, uncomplicated button-pushing. But if Albini seemed like a prick, he was a prick who defended punk’s credos – don’t sign to major labels, reject authority, say what’s on your mind, make a lot of noise – with uncompromising passion at a time when the counterculture was increasingly being assimilated, marketed and sold by the powers that be. “He had a real sense of wanting to do what’s right, not just for him but also for other people,” said Gerard Cosloy, who worked with Big Black at the now-defunct label Homestead.

In 1986, Big Black released their first LP, Atomizer, which the influential critic Robert Christgau described as “the brutal guitar machine thousands of lonely adolescent cowards have heard in their heads”. (In the same review, he also called them “hateful little twerps,”, no doubt aware of Albini’s reputation.) The band started to make consistent money and get real attention, but the bigger they got, the more they started to attract unpleasantly aggressive fans who did not pick up on the irony or humour in Albini’s lyrics. Kerosene, for example, is not a wholly sincere endorsement of arson and empty sex – it’s a commentary on the ennui bred in small towns and the nihilistic behaviour inspired by realising your life is never going to amount to much. “There was a gradually developing bro and jock contingent in the music scene. It infiltrated the hardcore scene pretty heavily, and it manifested in the frat version of alternative rock,” Albini told me. Punk rock could be juvenile, but there was a communitarian idealism in some of the best bands that came out of this world. That a chunk of their new listeners didn’t care about that gave Albini pause.

Big Black decided to put out one more record – 1987’s Songs About Fucking, which may be their best LP – and, after one final tour, call it quits. “The more time passes, the more correct I think that assessment was,” Albini said. “The band had persisted in making this hideous music and proven that if you have a valid set of working principles, you can do it on your own terms and never have to kiss anybody’s ass.”

One of the many things that differentiates Albini from other famous music producers is that he disdains the term producer. He prefers to be credited as an engineer, because it more accurately describes his belief that the job is simply to record the band, not shape their sound. He also doesn’t take royalties on any record, opting instead for a flat fee; he considers it unethical to make money off an artist’s work indefinitely, an otherwise accepted practice across the industry. (As proof of such conviction, consider the several million dollars he chose not to earn from his work with Nirvana.) But most notable is that he works with anyone, from the biggest of the big to the most obscure. He is not like Bob Rock or Rick Rubin or any number of superstar rock producers whose rates are unaffordable to anyone without a summer home. He is inordinately accessible – his email is public, as is his phone number, and during the interviews we conducted at Electrical Audio, the recording studio he has owned and operated for nearly three decades, I witnessed him answer the landline several times.

Albini’s career as a recording engineer began quietly. While Big Black were together, he supported himself with a series of odd jobs, but slowly, after he made himself available to record bands in his orbit, it started consuming more and more of his time, and he started charging. After Big Black’s breakup, he quit his job at a photo retouching company in order to make a full go of recording. He also founded an even more antagonistic band called Rapeman, whose name came from a Japanese manga and what Albini describes as a cynical need to repel as many people as possible. “I’m embarrassed by it now, but it was part of the decision-making process: ‘Look at all these fucking bands trying to get on MTV,’” he told me. “‘Whatever we’re doing with this band, it’s got to be 180 degrees opposite of that.’”

The name did not exactly diminish Albini’s reputation as an asshole. Their concerts were occasionally picketed and protested, and the band broke up within two years. In old interviews, Albini expressed irritation that people didn’t appreciate the subtle nuances of naming your band Rapeman: “The really annoying thing was that the majority of the people on the picket line were precisely the kind of people that we would have liked at the gig – people that politically basically think like we do,” he later said in the book Rock Names.

While these tendencies kept Albini’s own music a niche concern, the records he made with other people were starting to get more attention. He recorded Surfer Rosa, the debut album by the Pixies, who were at the time largely unknown; its radio-friendly sheen and alien peculiarities would place them at the vanguard of the alternative music that was starting to push into the mainstream. He logged time with many other bands – Fugazi, the Jesus Lizard, Hum, Silverfish, Helmet, Boss Hog – whose discographies spread across college radio playlists throughout the country.

But the album that catapulted him to another level of public notoriety was Nirvana’s 1993 LP In Utero. Charged with making a follow-up to their breakthrough album, Nevermind, and increasingly agitated about their sudden global fame, Kurt Cobain attempted to reject the critics who were questioning his credibility by enlisting the living standard of anti-corporate bullshit. “I had gotten a few woozy phone calls late at night from someone who didn’t identify himself but who said things to me about when Big Black played in Seattle,” Albini recalled. “I sort of engaged him in conversation for a while, and then made my excuses and ended the call – and that happened a couple of times.”

Shortly thereafter, rumours started circulating in the music press that Nirvana was preparing to work with Albini, though he’d never been formally approached. He and the band eventually connected, leading to a negotiation process where Albini laid out his philosophy for the record in a letter: “I think the very best thing you could do at this point is exactly what you are talking about doing,” he wrote. “Bang a record out in a couple of days, with high quality but minimal ‘production’ and no interference from the front office bulletheads. If that is indeed what you want to do, I would love to be involved.”

What became In Utero was, in fact, banged out in a couple of weeks in a Minnesota studio. But as he foresaw, Nirvana’s label, Geffen, interfered, insisting the record be remixed to soften Albini’s recordings. A compromise was eventually struck: the singles Heart-Shaped Box and All Apologies were smoothed out into more commercially friendly songs, while the rest of Albini’s work remained as is. “The three members of Nirvana I have absolutely no gripe with whatsoever,” Albini told me. “Every other person they worked with was a manipulative piece of shit who was putting pressure on them, scapegoating me and shit-talking this great record they made.”

For a while after In Utero, work started to dry up. Smaller bands assumed Albini was now too big to work with them; bands signed to major labels were no longer approaching him. “That was direct fallout from [major labels] blaming me for Nirvana getting uppity,” Albini told me. (Rossdale recalled that Interscope founder Jimmy Iovine told him: “You took a real gamble” about the band’s insistence on working with Albini.) Opening a studio is not cheap, and after buying the building that would become Electrical Audio in 1995, Albini worried that he might not tough it out. “I went broke several times, down to my last dollar, building the studio,” he said. He sold old recording equipment, old records, even the guitars he used in Shellac, the new band he’d started after Rapeman.

Then in 1997 he was thrown an unexpected financial lifeline from Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, formerly of Led Zeppelin, who were making their first studio record as a duo and decided to see if Albini was available. (In a 1998 interview, Plant said he was a fan of Albini’s dating back to Songs About Fucking.) The money and prestige from that album, Walking into Clarksdale, which was recorded at London’s Abbey Road Studios, helped keep Electrical Audio in business, and more work soon followed.

The project also served as an ego check. Page and Plant were not pals from the scene, nor were they familiar with Albini’s entire deal. (The members of Led Zeppelin were not keeping track of internecine conflicts in the punk world, no.) They were celebrities, legacy rock stars who would fly to Morocco at the weekend just because they could. “This was the first time that I was obviously hired by somebody,” Albini recalled. “They would have felt no compunction whatsoever about firing me on the spot if I disappointed them for some reason. That was heavy, realising that. So I did everything I could to avoid disappointing them.”

In 2001, the writer Michael Azerrad published Our Band Could Be Your Life, a history of the US independent music scene in the 1980s, which told the stories of bands like Sonic Youth, Fugazi and Big Black. What is striking, reading the book today, is not just how unrepentant Albini was about his past controversies – the appalling band names, the cruel insults, the jokes that toyed with racism, misogyny and homophobia – but how unbudging he was about why so many people had criticised him. To Albini, back then it was simple. Obviously he didn’t really believe in any of that stuff – if you read his interviews or thought about his music for two seconds, you would pick up on his real politics.

He had no time for people who are “careful not to say things that might offend certain people or do anything that might be misinterpreted”. That was just about seeming good rather than actually being good. “I have less respect for the man who bullies his girlfriend and calls her ‘Ms’ than a guy who treats women reasonably and respectfully and calls them ‘Yo! Bitch’” he told Azerrad. “The point of all this is to change the way you live your life, not the way you speak.” It did not seem to bother him that for people who don’t know your innermost thoughts and desires, the way you speak is the way you live; it doesn’t matter if you, personally, believe your politics are sound.

As the years wore on, his perspective started to shift. “I can’t defend any of it,” he told me. “It was all coming from a privileged position of someone who would never have to suffer any of the hatred that’s embodied in any of that language.” For years, Albini had always believed himself to have airtight artistic and political motivations behind his offensive music and public statements. But as he observed others in the scene who seemed to luxuriate in being crass and offensive, who seemed to really believe the stuff they were saying, he began to reconsider. “That was the beginning of a sort of awakening in me,” he said. “When you realise that the dumbest person in the argument is on your side, that means you’re on the wrong side.”

Kim Deal told me that Albini’s wife, the filmmaker Heather Whinna, whom he met in the 1990s, was a crucial influence. “She told him specifically: ‘I don’t think you know the power that you have when you just dismiss people. They really respect you, Steve, and why would you do that to them?’ I don’t think he understood that people were actually listening to him.”

Now whenever any public figure is made to answer for their former bad self, they go on an apology tour where they say all the right things about being a work in progress, and learning and listening, and so on. Rarely do they break down the actual specifics of what they said, why it was wrong and why they regret it. But Albini, when I asked him about his public reassessment of his past sins, was pretty no nonsense. “I thought it was important to explain how some of the uglier and more confrontational aspects of my speech and behaviour came about,” he said.

It would be naive to claim that someone like Albini might serve as a “model” for how others might revisit their past failures. He didn’t have a tidy series of epiphanies fit for a TED talk; instead he slowly changed his mind over a long period of time. Still, it was instructive to hear him connect the dots about why he had felt entitled to talk the way he once did. “It’s exhilarating to feel like there’s this forbidden area that you’re not allowed to participate in, and when you go in it, you feel like you’ve discovered a tropical island: ‘They told me there was nothing here, and look, there’s something here,’” he said. “I understand that exhilaration.” But, he added, “I also know that we’re not as safe from historical evil as I believed we were when I was playing with evil imagery.”

In 1985, for instance, Big Black released a single called Il Duce, whose cover featured a stylised rendition of Benito Mussolini, and which was dedicated, in tongue-in-cheek fashion, to the Italian dictator. “We gave ourselves licence to play with this language because we felt no threat from it,” he told me. “We thought [the far right] was a historical anomaly, a joke for lonely losers. Even as the right wing became more openly fascist, we were still safe – and that’s where my sense of responsibility kicks in, like: ‘Oh yeah, I get it now. I was never going to be the one that they targeted.’”

On top of his work as musician and engineer, Albini is an accomplished poker player: last summer he won $196,089 and earned his second bracelet at the World Series of Poker, which in layman’s terms is an award you get for being really, really good at playing poker. But there was a deeper meaning behind his attraction to the game, he explained. “In poker, there’s a layer of deception where you sometimes do things that are intended to be misleading,” he said. “In my regular life, if I tell somebody something, I want them to believe me. I’m not trying to induce mistakes in the people I interact with.” Poker was the only realm in which it felt appropriate to lie.

It was a neat summation of why he was talking so directly about his past pronouncements, and why he regretted them now. “It’s not about being liked,” he said, as we sat at Electrical Audio. “It’s me owning up to my role in a shift in culture that directly caused harm to people I’m sympathetic with, and people I want to be a comrade to.

“The one thing I don’t want to do is say: ‘The culture shifted – excuse my behaviour.’ It provides a context for why I was wrong at the time, but I was wrong at the time.”

It was a clear and honest apology, and it was the truth. And with that, we both fell silent for what felt like the first time since we’d met.

Another part of what changed Albini’s outlook was his work as an engineer. “It made me sympathetic to music and rationales that I would never have considered before,” he told me. When he started out, before he developed his hands-off ethos, he was more comfortable imposing his ideas on the bands he was working with. Today he laments some of his interventions, like the snippets of ambient noise and conversation woven throughout the Pixies’ debut album Surfer Rosa. (When I mentioned this to Kim Deal, she scoffed at the idea that the Pixies would have allowed anything on the record that they didn’t like.)

As he kept working, making hundreds of records across many more sessions, Albini became more comfortable stepping aside. Experiences like the Plant and Page record reminded him he was just a cog, there to enable someone else’s expression. These days, once Albini has agreed to record an artist, he begins by asking them to state their expectations, what bands they’re into, how they’d like to sound, how they’ve been disappointed in previous sessions. (The process is not unlike starting with a new therapist.)

Albini will do anything a band asks, but he has his preferences. He likes to record as few takes as possible; he prefers recording in analogue – as in capturing a band on magnetic tape – rather than digital; he discourages excessive tinkering, and once they’ve agreed on how they’re trying to sound, he prefers to have little to no input on an artist’s actual music. “My tastes as a listener are somewhat perverse,” he explained. “So if I was trying to indulge my tastes on someone else’s record, they would end up making a perverse record, and that would do them no favours.” When Albini was working with Bush, they asked for his opinion on their song Swallowed. After much hemming and hawing, Albini admitted he didn’t think it should make the album. It ended up becoming their first No 1 US single.

“He doesn’t want to give an opinion, but he’s also fucking opinionated,” Gavin Rossdale said with a fond smirk, making it clear that it didn’t take too much work to invite Albini’s input. “But he doesn’t want to interfere, and that comes from a pure place.” (And Albini is still comfortable goading people over more trivial matters, like when he recently expounded on how much he hates Steely Dan: “Music made for the sole purpose of letting the wedding band stretch out a little.”) Describing the environment he creates in the studio, Nina Nastasia used the word “comfortable” several times. “He’s so efficient and has such a knowledge about his craft, and you just don’t have to worry about doing your thing,” she said. “It’s great to just feel completely confident.”

Not everyone is a fan of Albini’s work: “For me, the record sounds like shit,” said Elvis Costello in 2020 of PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me. “That guy doesn’t know anything about production.” But the list of celebrated artists Albini has worked with – the Stooges, Slint, Superchunk, Sunn O))), Jarvis Cocker, Jawbreaker, Dirty Three, The Wedding Present, Songs: Ohia, Low, Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Mono, Mogwai – suggests Costello’s view is not widely shared. At one point I nudged Albini to talk about working with some of those artists, but while he was happy to discuss his approach to recording them in the studio, he didn’t offer much in the way of old-timey “remember when?” reflection. He wasn’t a nostalgic person, he said, and didn’t think about the past very much. “The recording part is the part that matters to me – that I’m making a document that records a piece of our culture, the life’s work of the musicians that are hiring me,” he said. “I take that part very seriously. I want the music to outlive all of us.”

Electrical Audio is built from mud bricks, which soak up sound. When a band isn’t recording, the rooms are deathly quiet, giving the entire building the sacramental feel of a cathedral. Before the pandemic, Albini was working non-stop; when we met last year, he’d generally been free about half of the week. It’s not a coincidence that Albini started publicly reflecting on the past around the time that his working life slowed down. There’s been more of a chance to pause and recognise how our culture has changed. Major labels slowly lost interest in rock bands. Millennials and zoomers, who came of age during lean years and remain financially precarious in adulthood, were simply less preoccupied with the concept of “selling out”, transforming that once-pressing debate into a historical relic. The internet blew up the traditional music industry. Punk rock increasingly became just another flavour of mainstream entertainment. And though it was never easy, it became harder and harder to earn a living from playing music as rents increased, payouts from labels decreased and the cost of everything went up.

All this might have been depressing to someone who’d borne personal witness to the potential of punk rock to transform lives, and I asked how and why Albini kept doing what he does. “There’s always been a predatory and exploitative level of the music industry,” he said. “But beneath the professional level, you have all the bands that operate the same way [Shellac] operates: it’s our outlet for the creative impulse.” To Albini, making art was something you simply do, without any need for grand external validation. Most of th