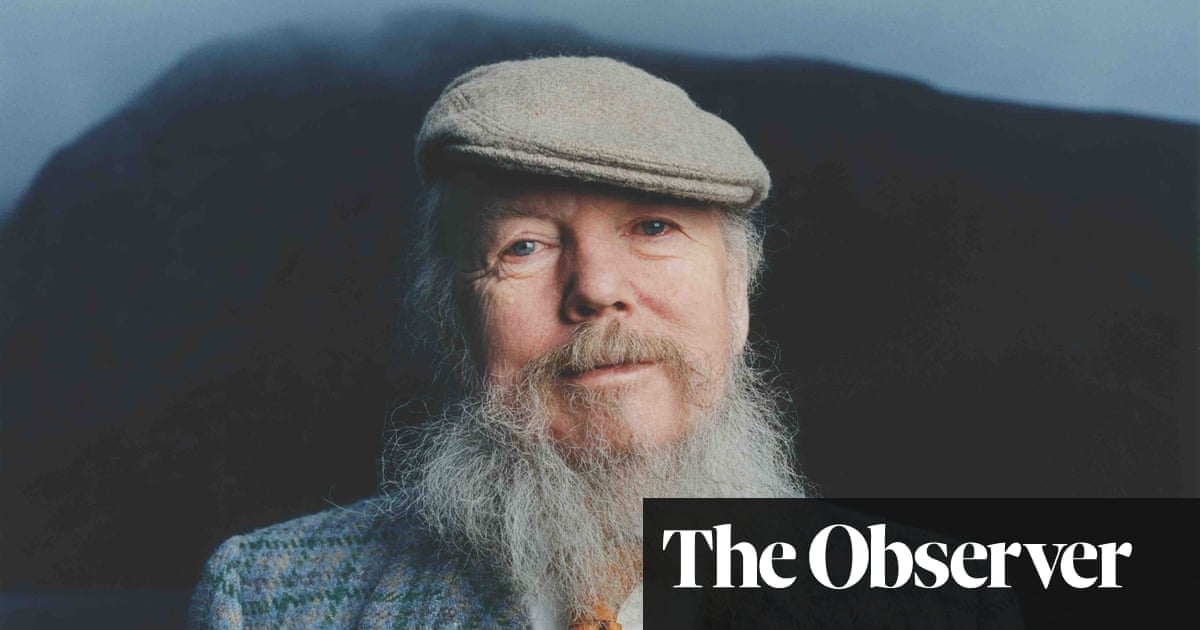

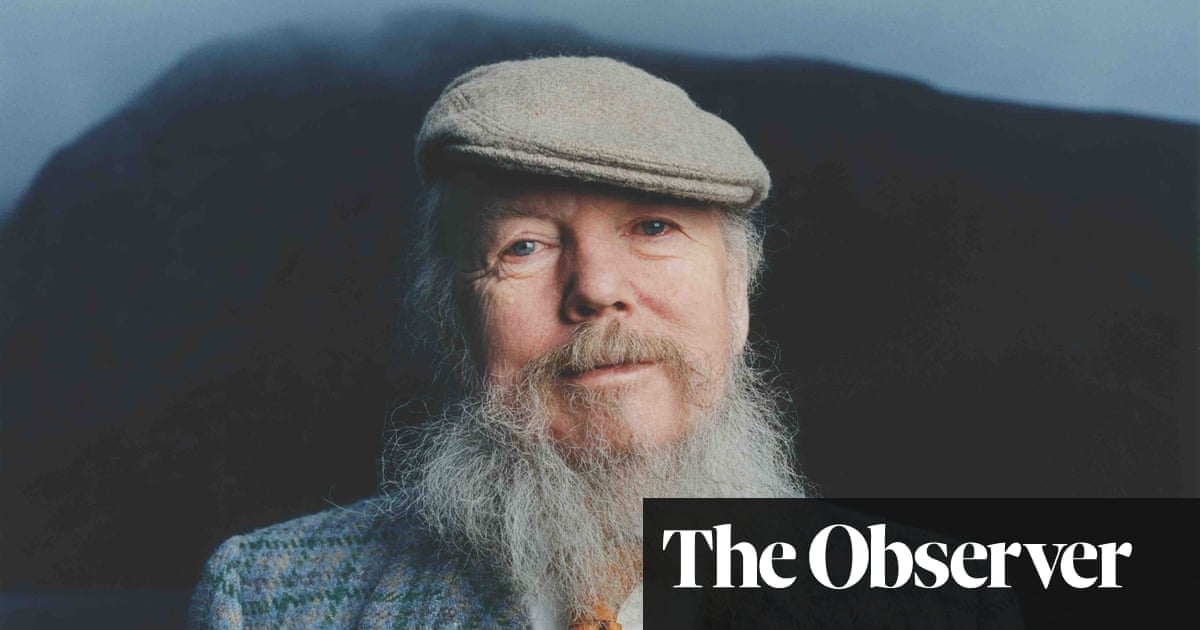

When Garech Browne was growing up in the 1940s, he fell in love with the traditional Irish tunes whistled by a worker on his father’s estate in County Mayo. Browne would toddle after him, enchanted, as if following the Pied Piper.

A strange, gilded, troubled life stretched before Browne. As an heir to the Guinness fortune, he would have a jetset existence of bacchanalia and celebrity friends, including Mick Jagger and Lucian Freud.

But while rock’n’roll conquered the world, Browne embarked on a quixotic mission to save the music of his boyhood – and centuries of musical and spoken-word heritage – from oblivion.

Emigration was depleting rural Ireland and its folk memories of melodies, songs and poems – a slow-motion destruction of a culture. Browne resolved to preserve what he could before it was lost in a task that drained his fortune and filled his life.

The story of that remarkable artistic rescue mission has now been told in a book, Real to Reel: Garech Browne & Claddagh Records, to be published next month. “Garech Browne knew what he wanted to achieve with Claddagh, namely the preservation of Irish traditional music, song and spoken word,” said the book’s author, James Morrissey. “He wanted the recordings to be simple and made in a manner that was sympathetic to the roots of the Irish tradition.

“It was a goal that was perceived as audacious by some and a folly by others, but what others thought bothered Garech little.”

Browne tracked down unknown singers, uilleann pipe players and other musicians – some of whom had never performed outside their villages – and recorded them, first with a Grundig tape recorder, then in studios hired by his company, Claddagh Records.

He helped in the formation of the Chieftains, a band led by the late Paddy Moloney who went on to win six Grammys, collaborate with the Rolling Stones, Madonna and Luciano Pavarotti, and popularise Irish traditional music around the world.

Browne also recorded poets reading their own work, notably Patrick Kavanagh and Seamus Heaney.

He became famous for hosting parties at his Luggala estate in County Wicklow, south of Dublin, drawing a crowd of actors, artists and film-makers and giving Ireland a taste of the swinging 60s.

In the book, U2 singer Bono compares Browne, who died in 2018, to the American folklorist Alan Lomax, whose blues recordings ended up in the Library of Congress.

“What Garech was doing with Claddagh was to preserve melodies that might never have been heard again,” he said. “He saw himself as protecting our music for us. It gave him a sense of purpose.”

Browne was eccentric and erratic, characteristics that many attributed to an unorthodox upbringing. He was the son of Dominick Browne, a baron who sat in the House of Lords, and Oonagh Guinness, a socialite and heiress to the brewing fortune.

Their eldest son loathed formal education – he once faked a telegram from his mother to flee a school in Switzerland. He was largely self-taught and mentored by his parents’ friends, including Freud, who took him to galleries. A Freud portrait of the teenage Browne in 1956, Head of a Boy, sold for £5.8m at Sotheby’s in 2019.

Browne’s passion for Irish music stemmed from his early years in Mayo. “I can remember dancing to Irish music at around the age of three. It is one of my earliest and most vivid memories,” he once said.

Browne feared that the advent of pop and rock’n’roll would accelerate the demise of Irish folk, so as a teenager he started making expeditions around Ireland – an incongruous figure with a Mercedes and posh accent – to record and archive songs and melodies. In 1959, he set up a company that went on to become Dublin-based Claddagh Records.Run by poets, musicians and dreamers, it was an administrative chaos not even Charles Dickens could have conjured, said a director, Richard Ryan. Yet Claddagh survived and nurtured talent such as the composer Seán Ó Riada and the singer Dolly MacMahon. Browne paid fanatical attention to album sleeves and artwork.

The musicians often joined the parties at Luggala. The actor Sean Connery was so moved by the fiddle playing of Tommy Potts that he wrote a poem about it. “He held us all / making sounds of beauty and despair.”

Browne amassed 20,000 books that were overseen by a librarian, Mary Hayes. He valued the spoken word as much as the printed one and so recorded poets and writers reading their own words, she said. “You only have the opportunity when the person is alive – you can’t resurrect them.”

Claddagh recorded Scottish as well as Irish writers – voices preserved for posterity, even if their talent is not yet fully recognised, said Hayes: “Maybe even now it’s still too early.”

Browne was a dandy and a spendthrift – he bought hundreds of suits and once flew to a London tailor to replace a lost button. He married Purna Harshad Devi Jadeja, the princess daughter of a maharajah, but struggled with alcohol, loneliness and mood swings.

“I was very grateful to have him as a friend,” said the Anglo-Belgian portrait painter Anthony Palliser. “He saved Irish traditional music. At the same time, there was a tragedy about him, a melancholy.”

He never got over the death of his younger brother, Tara, who died at the age of 21 in a London car crash in 1966, an event immortalised in the Beatles’ song A Day in the Life.

Browne died five years ago – over lunch at a London restaurant – at the age of 78. His ashes were scattered in a lake near his Wicklow estate.Ireland’s president, Michael D Higgins, paid tribute: “Not only is our generation indebted to him, but future generations will recall his insightful, pioneering work.”

In the book, Bono adds an epigraph: “Words and music, they were the most important things in his life.”

Browne’s legacy endures through Claddagh Records. Last year, it issued a remastered recording of Kavanagh reading his poems, and original recordings of rock stars, actors and others reading their own selections.