Museum-goers are to be transported back more than 3,500 years in a sniff after researchers identified and recreated the scent of balms used in the mummification of an ancient Egyptian noblewoman.

While mummification may conjure up scenes of bandages and jars, the process was a fragrant affair in which the body and organs were embalmed to preserve them for the afterlife.

However, with a dearth of texts from ancient Egypt revealing the exact ingredients used, scientists have been using modern analyses to unpick the substances involved.

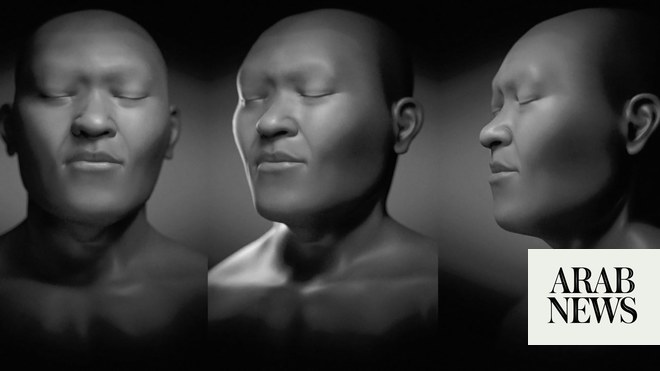

Now researchers studying residues of balms used in the mummification of a noblewoman called Senetnay have not only revealed that many of their ingredients came from outside Egypt but also reproduced their perfume.

“Senetnay’s mummification balm stands out as one of the most intricate and complex balms from that era,” said Barbara Huber, the first author of the research from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

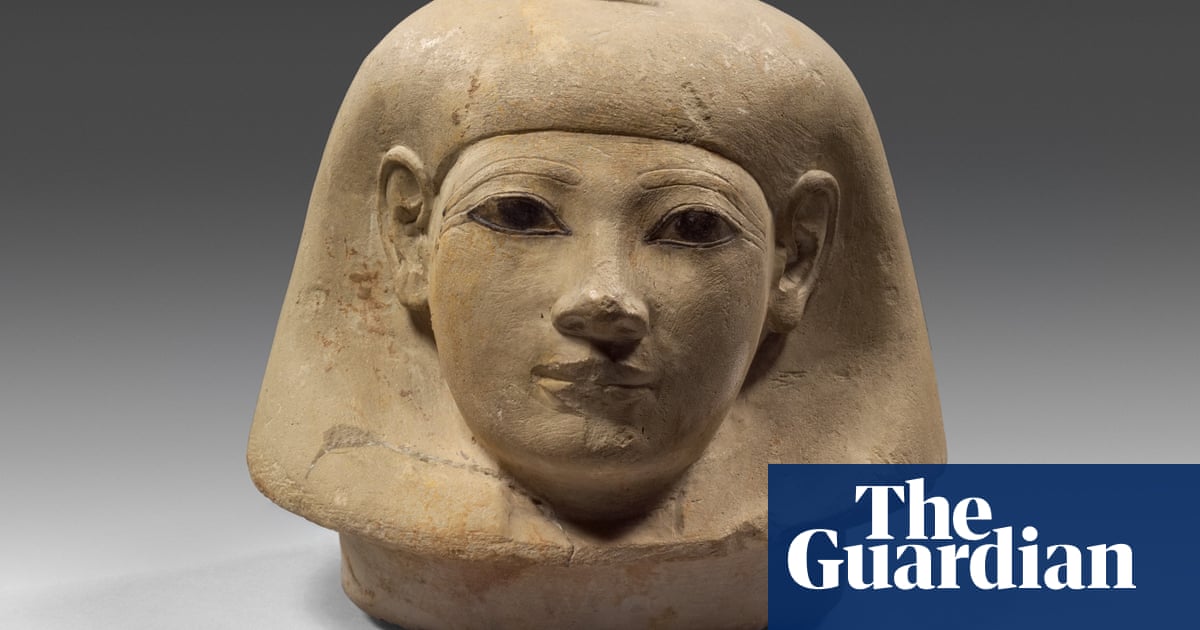

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, the team say Senetnay lived around 1450BC and was a wet nurse to Pharaoh Amenhotep II.

Senetnay’s canopic jars – vessels in which the deceased’s mummified organs were stored – were discovered in a tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1900 by Howard Carter, the British archeologist who would later become famous for his role in discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Huber and colleagues analysed six samples of residues of the mummification balms from inside two jars that that had once contained Senetnay’s lungs and liver, as indicated by hieroglyphic inscriptions.

The team found the balms contained a complex mix of ingredients, including fats and oils, beeswax, bitumen, resins from trees of the pine family, a substance called coumarin that has a vanilla-like scent, and benzoic acid, which can be found in many plant sources including cinnamon and cloves.

Many of the ingredients, they note, would have had to be imported to Egypt.

“For instance, certain resins, like the larch tree resin, likely came from the northern Mediterranean and central Europe,” said Huber. “One other substance was narrowed down to either a resin called dammar – exclusive to south-east Asian tropical forests – or Pistacia tree resin. In case it was dammar, this would highlight the extensive trade networks of the Egyptians during the mid-second millennium BCE, bringing in ingredients from afar.”

But not all of the ingredients identified were present in both of the jars, a finding that might suggest the balms were organ-specific, although the team noted it could also be that they were originally the same but were poorly mixed or had degraded differently.

The researchers said few mummies had received the elaborated treatment Senetnay was given, which, with the non-local provenance of many of the ingredients, supported the view that she had a high social standing – a situation already indicated by the site of her burial and her title, Ornament of the King.

Huber added that, working with a perfumer, the team had recreated the balms’ scent, which would be used in an exhibition at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark this autumn.

The smell of the balm has been labelled “the scent of the eternity”.

Dr William Tullett, an expert in sensory history at the University of York, who was not involved in the work, said recreating smells from history was crucial to understanding the relationship between the past and the present.

“To our noses, the warm, resinous, pine-like odours of larch might be more reminiscent of cleaning products and the sulphurous scent of bitumen might put us in mind of asphalt. But for Egyptians, these smells clearly had a host of other meanings related to spirituality and social status,” he said. “It’s those revealing comparisons between the here and now of smell that make recreations so interesting.”