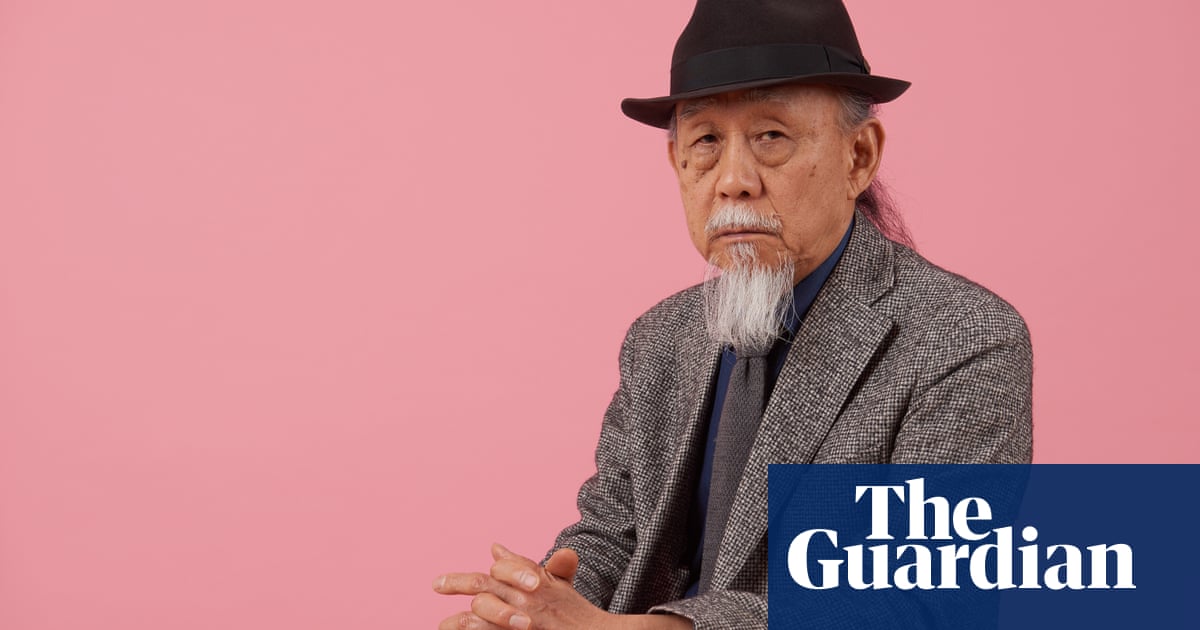

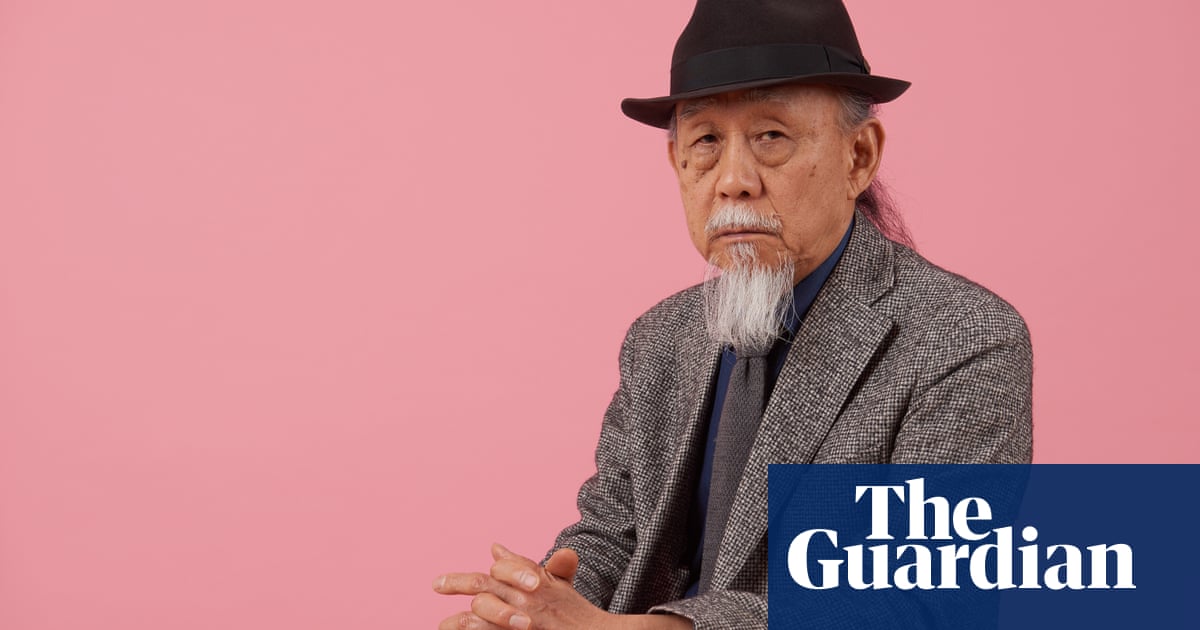

What is the moral responsibility of the artist? With balding pate, white goatee and mischievous mien, Sung Neung Kyung is sitting in his studio in Seoul, South Korea, looking back half a century to the country’s authoritarian regime and wondering whether, as a radical young artist, he made a difference.

“I have to say, thinking back to my artistic practice then from the luxury of hindsight, I feel that my activities at the time were not political enough,” he says via an interpreter beside him on a Zoom call. “I feel that I was carrying the voice of a mosquito. It was just so small and, because of that, I am ashamed.”

Yet Sung has much to be proud of. A pioneer of the South Korean avant garde, he has spent decades relentlessly pushing boundaries through photography, newspaper-related installations and an idiosyncratic brand of performance art. Now, at 79, he is enjoying late career validation. His work features prominently in Only the Young: Experimental Art in South Korea, 1960s–1970s, a group exhibition that opened on Friday at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York.

The show honours a generation of artists who broke from the past with their daring use of photography, video and materials such as barbed wire, cigarettes and neon, and by staging performances in theatres and along rivers. “It is being held in New York, the heart of the US, so as an artist it’s not bad at all,” smiles Sung, a playful interviewee who at one point offers a cup of coffee through the Zoom screen.

“In the ’70s, when I first introduced my art, the Korean art scene was not particularly impressed. I did not make a very good impression; I did not make any impression, really. But now I have the occasion to exhibit at the Guggenheim and just this year alone I had the honour to engage about three different solo exhibits as well. So I believe that I have gained some measure of recognition in Korea and I have to say it feels good.”

Born in Yesan, in what became South Korea, in 1944, Sung grew up in the shadow of war after North Korea, supported by the Soviet Union, invaded the south, supported by the US, in June 1950. The war raged for three years and led to the deaths of 3 million people and to tens of thousands of casualties.

He recalls: “I believe I was seven years old when I decided to become an artist. I remember fleeing the war and the family had to hide out from the war. I was staying with an older cousin and he was the one who suggested that maybe I think about pursuing art as a career.”

The cousin in question was an aspiring poet and English language and literature professor at a university in Seoul. “This cousin’s influence, his artistic sensibilities, were absolute over me throughout my youth and all the way until my college years. In fact, I remember listening to him recite the poetry of poets such as Dylan Thomas and William Blake. That was the foundation of the artistic sensibilities that were established in me.”

Sung majored in art at university but had to perform military service from 1970 to 1973. “You have to remember this was during the time that President Park Chung Hee was in power and those were quite dark times for Korean contemporary history. The military service was compulsory, so I had no choice. I have to say it was quite challenging. It was a very difficult time in my life. But I also have to say that it was nothing compared to the challenges that I had to undergo as an artist.”

Sung joined the avant-garde group Space and Time, an art and research collective that was swimming against the tide. “In Korea at least, conceptual art was not necessarily popular,” he recalls. “In fact, people looked down on you if you said you were a conceptual artist. Around that time in the 1970s, the creative art scene was trying to carry on the eastern tradition, so artists would only be regarded as bona fide legitimate artists if they incorporated ancient Chinese scholarly scriptures and ideologies coming from Buddhism or the teachings of Lao Tzu or Sun Tzu.

“What I tried to do was probe into my own existence using conceptual art as the perspective and that kind of art was looked down upon. What I was trying to do was go off the beaten track, go where no one has gone before. These are the artistic meanderings that inspire my work and are what I wanted to do, because ultimately I feel that I am me, I have always been truthful to myself and I have not been swayed or influenced by any different kinds of trends over the years.”

Sung was also trying to find his voice under the stifling dictatorship of Park, credited for leading the country’s economic rise but condemned for widespread abuses of human rights. Park’s 18-year rule ended after he was gunned down by his intelligence chief in 1979, five years after his wife was killed during an assassination attempt that targeted Park.

The artist says: “I remember at the time many literary authors were subjected to arrests and detentions by the regime but not necessarily painters and artists. Because their means of expression is more indirect not many of them, compared to poets and writers, were arrested by the political regime.

“It’s also due to the fact that these artists and painters would self-censor themselves from voicing anything that could be read as social or political. That was why the artists would turn to other means of expression. So this was around the time that Dansaekhwa, the monochromatic paintings, and dimensional art became popular. If you think about it, it was even worse and more scary because nobody had to tell the artists or censor them from the outside. They would just censor themselves.”

Sung’s first major work was Newspapers: from June 1st 1974 during which he hung each day’s Dong-a Ilbo newspaper on a gallery wall, carefully removed each block of printed text with a razor blade and put them in a box. “It was an act that I engaged in personally to try to resist the politically and socially oppressive atmosphere that was prevalent in Korean society around the time due to the Park Chung Hee regime.

“In fact those years of the Park Chung Hee regime were the starting point of my art practice. Those years inspired me to take an interest in dissolving or dismantling the editorial authority or power that many newspapers and the media wielded over Korean society at the time.

“The piece involved my having to clip out articles that were featured in daily newspapers. I wanted to ask these questions. What is the identity of a newspaper with all of these omissions in them? When these newspaper articles have been clipped out, then you see these blanks in the newspaper pages, what does that represent? What do these blanks represent? I just wanted to ponder and question the underlying potential meaning in all that.”

Sung then pivoted from the political to the personal. His next work, S. at Mid-Life, featured photos he had taken from boyhood up to the age of 35. They included closeup shots of his own face blown up into big prints, with silk-screen printing over them. “Looking at the pictures, you would feel as if you were looking into these blacked-out faces of criminals almost, and I do believe that this work is without precedent in Korea.

“In effect you would see that the work Newspaper: from June 1st 1974 is a very public piece wheras S. at Mid-Life is a very private piece. They’re contradictory to each other in some ways. However, the S. in Mid-Life piece, while being very personal in nature, was exhibited in a public space. With that I was trying to blur the boundaries between the public and the private and erase the gaps that existed between the public and the private sphere.”

In a 1976 work, Apple, Sung produced sepia-tinted black-and-white photographs of himself biting into an apple and traced its changing shape with a marker pen. He says cheerfully that it follows a thread from Adam’s apple to scientist Isaac Newton’s apple to a Korean poet whose description of an apple falling and hurting the world seemed to foretell the climate crisis.

“I would like to think that I was also helpful in drawing this demarcation line where there was conceptual art before me and then there was conceptual art after me in the Korean art scene. Perhaps I was also contributing to predicting this change that was going to happen in Korea, specifically in the art scene, and then my apple was followed by a Steve Jobs’s Apple, which completely revolutionised the world.”

Sung’s performance art often features self-exaggeration, loud noises and outrageous clothing such as a bathing suit and shower cap. For Aluminum-Foil Man in 2001, he worked with a photographer to represent himself with varying martial art poses dressed in underpants, sunglasses and skimpy swaths of aluminum foil. He will perform at the Guggenheim on 17 and 18 November.

He muses: “One of the key advantages of performance art is you engage the audience in a relationship. This is a relationship that you cannot build with existing artistic genres. When I engage in performance art, I’m able to see this corridor through which I can take the audience with me and we can enter into the same artistic world together.

“But I feel that, for many artists, performance art is something they pursue when they’re young and then they discard later on in life. It has to do with the forces of capital markets and art entering into the territory of capital earning. It’s all about making money, so then it becomes difficult to pursue performance art later in life. Whereas for me, I found it difficult to give it up because performance art has the ability to bridge invisible gaps between the artistic genres.

He adds with a twinkle: “If I were a smarter man, if I were a wiser man, then I probably would have taken a different path in life, in my artistic career. But I am quite dull, not the smartest person, so I just remain confined to what I like doing. This dull-wittedness of mine has been a constant companion throughout my life.”

Sung thinks about art all day and all night and never stops experimenting. He holds up his phone to the Zoom camera and swipes through some colourful digital works that he made while sitting on the toilet. He explains his thought process: “I’m not very fluent in English; I’m terrible at it. But I looked up the word ‘anthology’ once because in Korea it is used to represent collections of written works or, with many of the K-pop boybands or girlbands, anthology refers to their whole collection.

“The origins of the word ‘antho’ means flowers and ‘logy’ means collect, so basically it’s like a collection of flowers, a bouquet. This is what people would lay before the altar of the gods that they worship. For me, because I do this work on a toilet, it would be ‘shitology’. I thought to myself, what represents the altar of beauty in the modern-day world? Oh, art museums, galleries. So I am presenting this work of shitology to this altar of beauty and, with that in mind, I have been working on this since 2020. This is a bouquet of shit that I am presenting and holding up and before the altar of capitalism.”

When all is said and done, does Sung regard himself as a political artist or an apolitical one? He replies through his interpreter: “It is my belief that all art is fundamentally at least a little bit political and because of that, inherently, my art is also slightly political. It just so happened that in the ’70s it was a little bit more overtly political. When it comes to the fact that art delves into the existence, the raison d’être of these artists, it becomes political fundamentally. I feel that is what art is all about.”

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s is on display at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York until 7 January 2024