“Drawing, always, was the through line.” So concludes Whitney curator Kim Conaty in her introductory essay to the catalogue for the exhibition Ruth Asawa Through Line, which she co-curated with the Menil Drawing Institute in Houston. Among other things, Ruth Asawa Through Line seeks to demonstrate the centrality of the daily practice of drawing to both Asawa’s life and her artistic world.

Asawa is best-known for her elaborate hanging wire sculptures – sinuous, organic-like forms that stretch on and on in intricate, interleaved chambers, bearing a mysterious presence and casting extraordinary shadows. She began experimenting with them in the 1940s while a student at Black Mountain College, studying under the likes of Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham and Buckminster Fuller, and she began earning substantial attention for her sculptures throughout the 1950s.

By the late 60s, however, Asawa’s star was declining – there was little room for an Asian American mother of six in the art world of the era. She fell into relative neglect until very late in her life, and finally began to receive her due after her death in 2013. As part of that re-evaluation, Through Line is an attempt to open up a new side of Asawa’s art, one that meshes with a central aspect of her art practice. “Drawing was her center of gravity,” Conaty told me during an interview. “It was this critical part of her life, a place where she was able to play out so many ideas.”

Conaty has long been a fan of Asawa’s drawings: one of the first prints she purchased as a curator when she arrived at the Whitney was one that Asawa made by stamping it out with a potato as her implement. For Conaty, this print was a way into Asawa’s world, and more and more she began to appreciate Asawa as an imaginative creator and fierce advocate for the arts. As Conaty got to know two of Asawa’s children, she was able to see her drawings firsthand, and what she saw amazed her. “At that moment, I just thought, ‘this is just beyond my wildest expectations!’” she said. “Being a drawings curator, when you see someone with such simplicity and yet technical dexterity – the playfulness, the life in her drawings, it all really bowled me over.”

Through Line grounds itself in Asawa’s time at Black Mountain College, where she both began experimenting with wire sculpture and absorbed lessons about art that she would carry through her life. “Albers taught his students not how to draw but how to see,” said Conaty. “As Asawa once explained, it wasn’t about graduating from paper to sculpture, it was about graduating from paper to paper. A lot of these ideas were part of her learning environment at Black Mountain College. The resonance of the teaching at BMC was something we really wanted to bring out in the show. She took these lessons with her throughout her life.”

From this period comes an absorbing, stamped ink piece in which Asawa repeated a stamp reading “DOUBLE SHEET” up and down a piece of paper. In its cramped, tilting columns and its movement from compression to spaciousness, the work takes on a mesmerizing quality. According to Contany, Asawa found the stamp while working in the Black Mountain College’s laundry room; making art out of found objects was to become a lifelong practice that would see her also using potatoes, bike pedals, fish and leaves, among other things. “It’s part of Asawa’s penchant for scavenging, and for seeing things in the world around her and turning them into mark-making tools,” said Conaty.

Through Line is organized by theme, with “Learning to See” covering her time at school and “Found and Transformed” highlighting Asawa’s penchant for scavenging. Other themes include “Forms within Forms”, which offers insight into how Asawa’s sculptures fit within her drawing practice, “In and Out”, which examines Asawa’s paper folds, and “Curiosity and Control”, which showcases the artist’s watercolors and ink drawings. For Conaty, the richness of the multitudes of art on display is magical. “All of us in the galleries are walking from space to space, just lifted up,” she said. “There’s something very viscerally powerful about this work.”

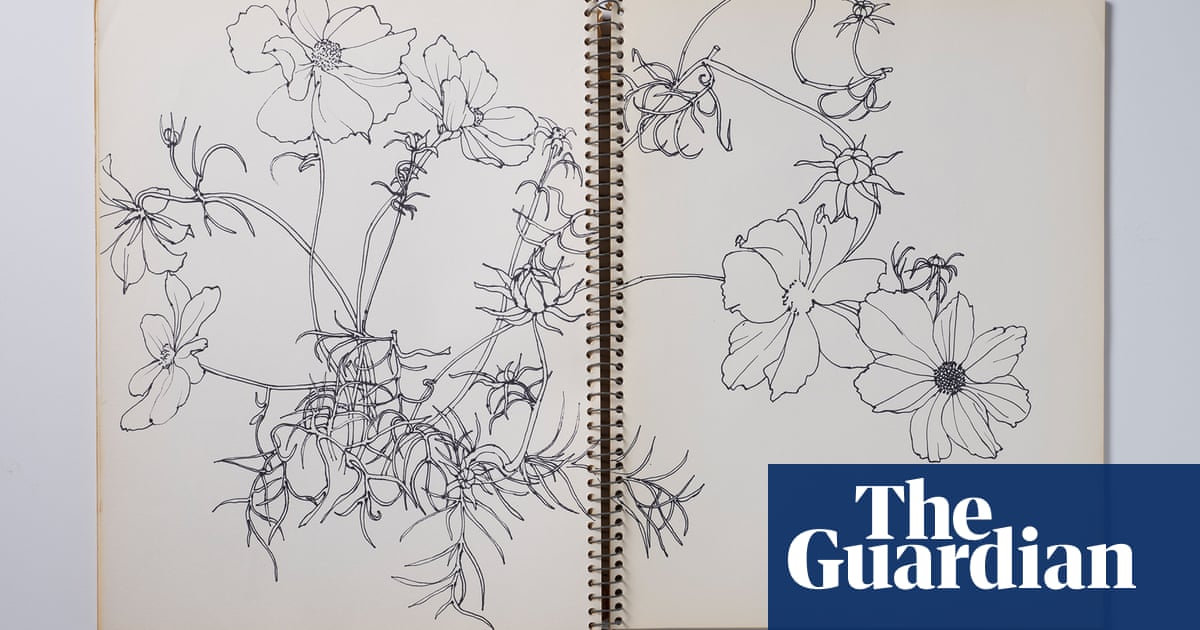

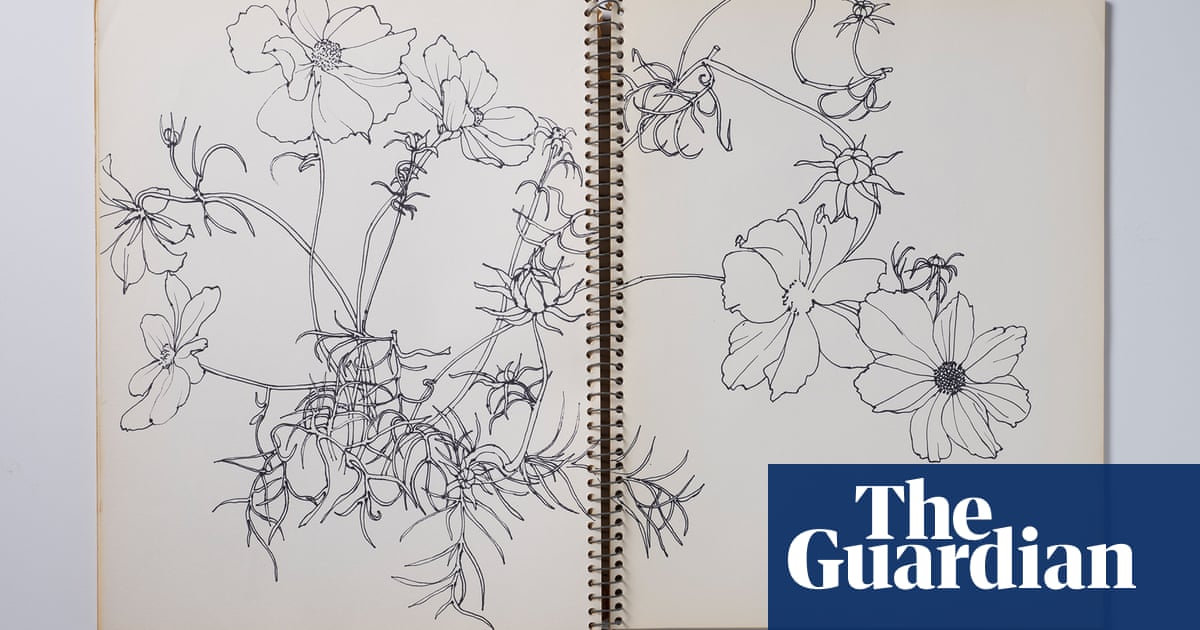

Asawa’s drawings tend toward opposites, some appearing mysterious and abstract while others engaging the quotidian and concrete. On one end, her papers are suffused with amoeba-like blobs and tentacles as well as strict geometric form, either wandering out across the page or stamped obsessively in colony-like forms. On the other end are portraits of whatever happened to be at hand – Asawa’s husband, her children, friends, even politicians on TV talk shows. Some of Asawa’s drawings also transcend the divide between abstract or not: forms like chairs or trees or a watermelon are pushed into the realm of abstraction, still retaining something of their original form but more suitably viewed as pure shape and color. This is all part of the dailiness of her drawing practice, which saw the artist coming back to the page time and again, like a touchstone, using whatever was at hand to create with.

Through Line focuses mostly on Asawa’s more abstract art, keeping her portraiture to just one section entitled Life Lines. That would seem to be a good decision, as the non-representational art feels more alive and inspiring. The abstracted drawings tend to have an intricacy that is truly amazing – in their variability and their obsessions they create a sense of vibrancy and vitality, and over time they come to offer much insight into the creative brain of the woman whose sculptures have established their own territory in the art world.

Conaty shared that curating Ruth Asawa Through Line was not just about interfacing with wonderful artwork, but also about engaging with an inspiring life. She told me by curating this exhibition, “I learned about the power of an individual. It very much feels that everyone in her world that she touched was changed by that encounter in a positive way.” Asawa’s life was by no means an easy one, as she and her family lost very much as a result of being forced into a concentration camp for Japanese Americans during the second world war, but art really did offer a lifeline. “She found salvation in art-making,” said Conaty. “She chose to work at home with her family, and everyone would be a part of this work. Her hand was always moving. She would always be drawing, and that was really her way of listening.”

Ruth Asawa Through Line is on view at the Whitney in New York until 15 January 2024