A large majority of Scottish voters support proposals to allow terminally-ill people to take their own lives, according to a poll released by campaigners for assisted dying laws.

A new bill to legalise assisted dying in Scotland is due to be published by the Scottish parliament later this year, in a fresh attempt by its supporters to get the measure enacted for the first time in the UK.

The YouGov poll for the campaign group Dignity in Dying found that 77% of Scots supported the measure, with 12% of those questioned opposing it.

Its findings also suggested attitudes have shifted in favour of the legalisation among those with a religious faith, even though it conflicted with most religious teachings.

Earlier this year the general assembly of the Church of Scotland, the country’s largest faith group, suspended its historic opposition to assisted dying. It voted to explore “the range of theological views and ethical opinions” on the issue before deciding on its stance at a later date.

The poll found majority support for the bill’s measures among Church of Scotland members, Anglicans and – in another potentially significant break with religious teachings – Roman Catholics, although those samples in the poll were small.

A majority of the 354 respondents who had some or “a lot” of life-limiting health or disability issues also backed it, with a small majority saying they would “possibly” or “definitely” consider travelling to an assisted dying clinic in Switzerland.

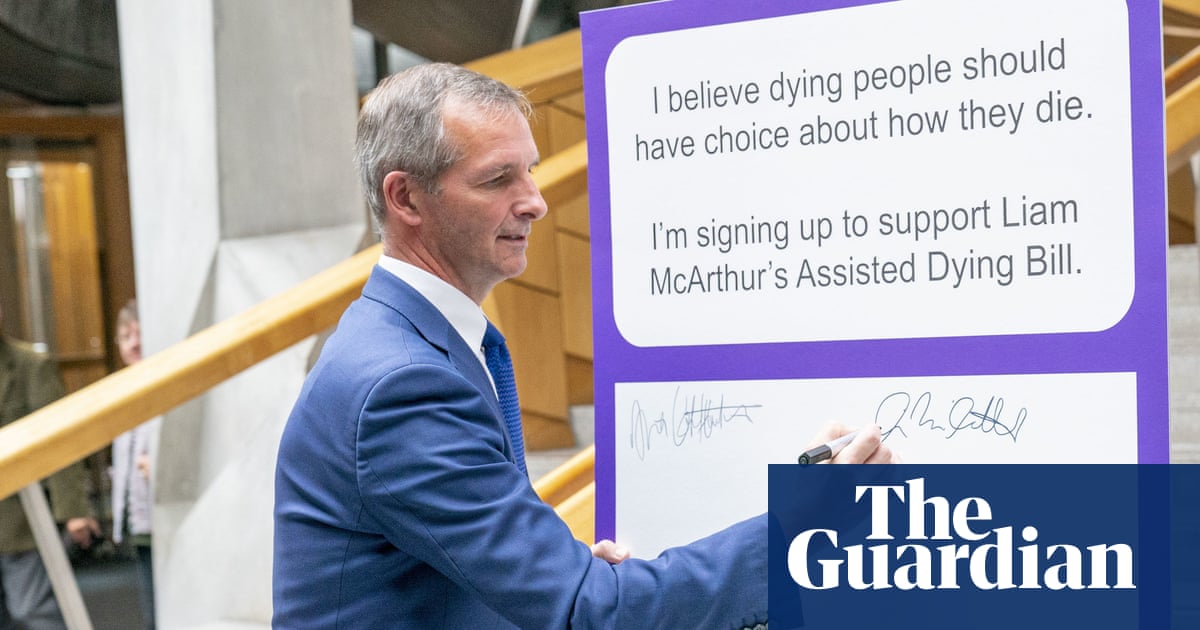

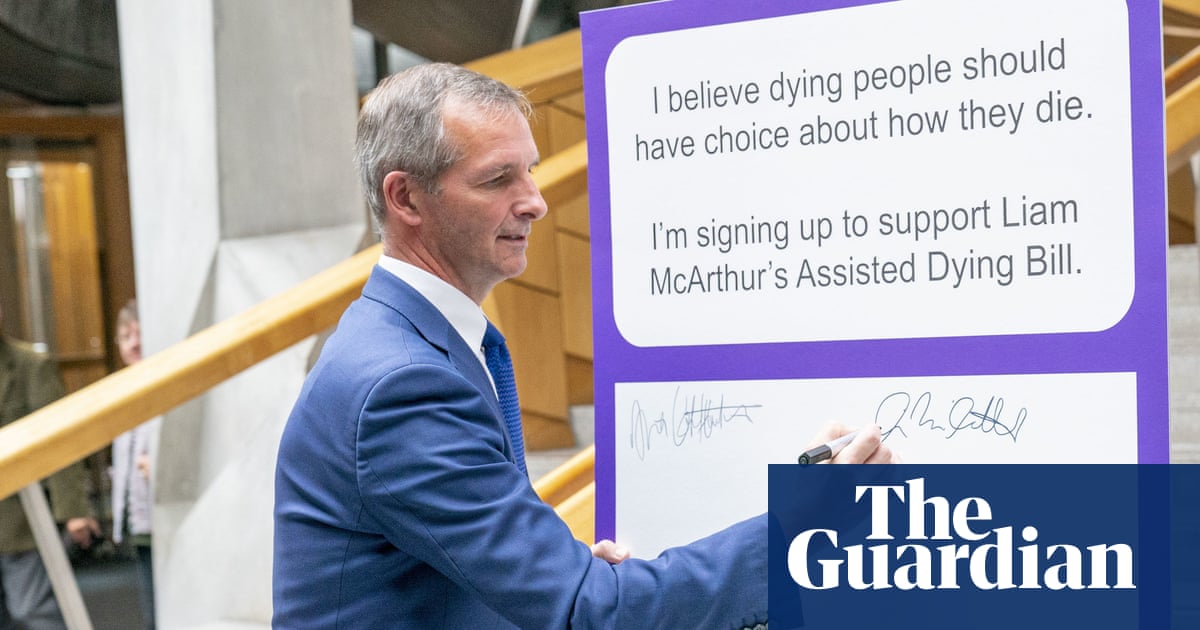

Liam McArthur, the Scottish Liberal Democrat MSP who is tabling the bill, said these findings, which echo other recent polls, proved the measures were widely supported.

“We know that excellent palliative care is the right path for the majority of dying people but there are also those who face a bad death, dying in great distress,” he said. “Tightly safeguarded and compassionate assisted dying laws not only give dying people what they need but protect all other groups as well.”

His bill has been supported by 36 MSPs from all parties – double the number needed to table a private members’ bill – but it is expected to be fiercely opposed by disabilities rights and faith groups.

Opponents argue it is ethically wrong for the state to approve suicide, and that once even limited rights to assisted dying are in law, the pressure to reduce the restrictions on eligibility will inevitably grow. They say it would put vulnerable, weak and poor people under greater pressure to choose assisted suicide.

Earlier this month Humza Yousaf, Scotland’s first minister, and the health secretary, Michael Matheson, said they were opposed to the measure, as has Anas Sarwar, the Scottish Labour leader.

Yousaf and Sarwar are practising Muslims; Matheson is Catholic. Islam, like Judaism and mainstream Christianity, proscribes suicide. The handful of Muslim, Baptist and evangelical voters polled by YouGov opposed assisted dying.

McArthur’s bill will be the fourth attempt to introduce assisted dying legislation at Holyrood, which controls the law in Scotland. None have yet been fully considered by MSPs.

In an effort to allay fears the measures will be too broad, McArthur’s bill will be more restrictive than previous proposals in Scotland.

It will only be open to those who have a certificate signed by two doctors stating they are terminally ill, of sound mind at the time of the procedure, and under no pressure. Doctors can seek specialist opinions about an applicant’s mental capacity.

Applicants must administer the life-ending drugs themselves, including using technological aids to trigger the injection. They must have lived in Scotland and been registered with a doctor for at least a year.

The British Medical Association and Royal College of Physicians have recently ended their historic opposition to assisted dying and instead adopted neutral positions, with increasing numbers of doctors now endorsing the measure.

Yousaf told the Daily Record his opposition had hardened after meeting disability rights activists in Glasgow. “They were incredibly strong in their opposition to assisted dying, given that they felt that they would be the ones, as they described it, that would be the thin end of the wedge,” he said.

Miro Griffiths, a research fellow in disabilities studies at Leeds university and a spokesperson for Better Way, a campaign group which opposes assisted dying, said helping people take their own lives would create “a really dangerous precedent for the role of the state in the way it protects life”.

In normal circumstances the police, social services and NHS worked to prevent people taking their own lives, yet here it was being facilitated, he said. The lessons from other countries where assisted dying was legal were that “once the legislation is passed, you will create pressure to widen the parameters of the legislation”.