In 1969, Samuel Beckett and his wife learned that he had won the Nobel prize in literature in a telegram from his publisher. “Dear Sam and Suzanne,” it read. “In spite of everything, they have given you the Nobel prize. I advise you to go into hiding.” Both were notoriously celebrity averse. Suzanne described it as a “catastrophe”. Beckett declined to give a Nobel lecture, and refused to talk when a Swedish film crew tracked him down to a hotel room in Tunisia, leaving them with a surreal mute interview.

Into this temporal void, a new psychological biopic has poured a monumental reckoning, in which the 63-year-old playwright scrambles out of the Nobel ceremony to find himself in a rough-hewn underworld. In Dance First a small masterpiece that premieres next month at the San Sebastian film festival, Beckett confronts the events and the people that shaped him, from his domineering mother to his experience with the French resistance, his brief dalliance with James Joyce’s daughter, Lucia, to his later inability to choose between Suzanne and the radio producer and translator Barbara Bray.

“You know this is going to be a journey through your shame,” he solemnly informs himself. “Isn’t everything?” he replies. It’s interior monologue played as dialogue, presenting an unusual challenge for the actor Gabriel Byrne, who found himself in an old quarry outside Budapest for three days, speaking to a broom.

“Well yes, that was difficult,” he says over video from his farmhouse in Maine. It wasn’t that the idea of speaking to himself was alien – far from it. “I’d spent my entire life talking to myself: even when I was a child in Dublin, I used to walk around the streets doing it, and if somebody walked past me, I’d pretend I was singing. But technically it was difficult because you had to do one guy here. And then you had to turn around and become the other guy. So the brush was standing there and you had to talk to the brush. And then you stood where the brush was and talked to … a brush.”

It’s as if the ghost of Beckett himself is hovering over Byrne’s shoulder as he describes the scene, a genuine desire to explain meeting the comedy of exasperation, as he realises that the only way to get his meaning across is to repeat the word brush. It is a small failure of verbal economy that is rendered both funny and telling, in an entirely Beckettian way, by a momentary pause. These things matter to Byrne, who proved himself a writer as well as an actor with a lyrical memoir, Walking With Ghosts, followed by a solo show he based on it, which transferred from Dublin to London’s West End last year.

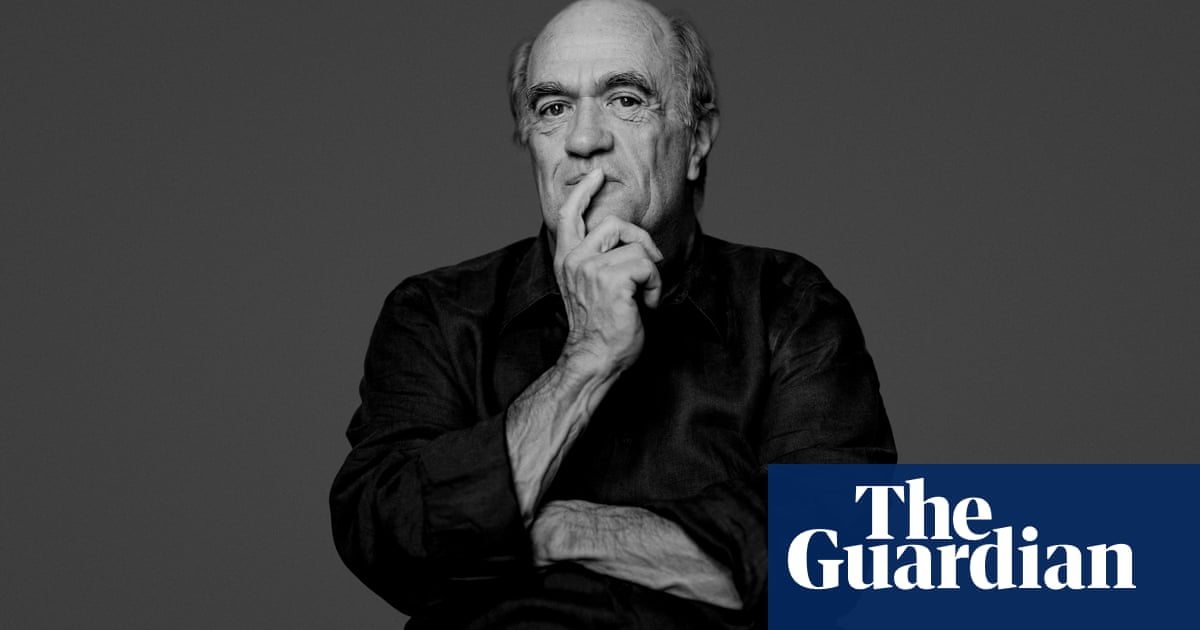

Apart from a “thrice broken nose”, which gives him a passing resemblance in profile to beaky Beckett, the genial, award-winning actor looks nothing like the creased and gimlet-eyed seer that the playwright had become by the time of his Nobel win. “I was really happy when I read the script, because it’s not trying to present a cradle-to-grave biography. I didn’t have to do it with wire glasses, and grey hair standing up on end, and lose maybe 30 pounds,” says Byrne. And yet such is the power of the storytelling that within minutes you believe in him entirely.

“Gabriel was the first choice I made. He’s had a very interesting career and hasn’t pigeonholed himself at all,” says director James Marsh, who began following Byrne’s career years before The Usual Suspects made him a Hollywood star – starting with his role as an ambitious young journalist in the 1985 parliamentary conspiracy thriller Defence of the Realm.

Dance First takes its name from a line in Waiting for Godot that has passed not quite correctly into literary lore as “Dance first, think later.” (The exact formulation, articulated by the tramp Estragon about Pozzo’s slave Lucky, is “Perhaps he could dance first and think afterwards.”) It is the first feature of Scottish screenwriter Neil Forsyth – best known recently for the TV heist series The Gold – and arrived, unsolicited, on Marsh’s desk, during the pandemic.

“As soon as I read it, I saw Gabriel in it,” says Marsh, whose Oscar-winning biopic The Theory of Everything, concerned another chewy genius – Stephen Hawking. “Obviously to play Beckett is quite daunting for an Irish actor, because he is so much part of their literary canon, but he didn’t need persuading and immediately approached it with great seriousness. He was a very nice presence on the set.” Sandrine Bonnaire joined Byrne as Suzanne and Maxine Peake as Bray, with Fionn O’Shea as the oldest of Beckett’s three younger selves. “It is a small art movie, but they all came with ideas and enthusiasm,” says Marsh.

All but the last of the film’s five episodes are played in statuesque black and white, echoing and – in one memorable scene in which Beckett is stabbed by a pimp with a wall of prostitutes looking on – directly replicating the work of Brassaï. The Hungarian photographer snapped the playwright at the height of his fame for Harper’s Bazaar, but it is his earlier pictures of Parisian nightlife that set the tone, capturing Beckett’s wayward early years, and his shadowy life with the French resistance, when he met up with Suzanne and life took a more dangerous turn, albeit often characterised by the enemy’s failure to turn up as expected.

In all his decades as one of Ireland’s most successful acting exports, this is the first time Byrne has had anything to do professionally with Beckett’s work, and he is dismissive of some of the productions he has seen, notably Waiting for Godot in New York in 1988, starring Robin Williams and Steve Martin: “There was one moment when I thought, this is meant to be funny. Yet here are two of the funniest men on the planet, and they haven’t raised a laugh between them.”

There’s a reverence for Beckett that gets in the way of the humanity of his work, he believes. “It happens with Eugene O’Neill too” – whose plays have been something of a Byrne speciality. “People are so in awe of what they represent, that they surrender to that awestruck notion that these men are speaking from the top of a mountain. But Beckett was not speaking from the top of a mountain but from the depths of his soul. And the way he expressed himself was through this pared down, essential simplicity of language, expressing the deepest and most complex of feelings and thoughts about what it means to be human.”

He wouldn’t have done the film if it had been a conventional autobiography, he says: “How do you tell somebody’s life in an hour and a half? It’s not possible. A lot of these biopics depend on the likeness of the actor to the person they’re playing. And it becomes about an impersonation, structured around the highlights of the person’s life. There’s nothing wrong with trying to do a film like that. But I think the braver course was to do something that tried to encapsulate what Beckett was as a human being.”

He applied the same principles to his own life in his memoir. “Memory is so unreliable,” he says. “It doesn’t have a structure to it. It doesn’t have a linear quality. It comes for a couple of seconds and disappears. And you’ve no idea when it’s going to come again. The present and the past are always overlapping. I was interested in finding out: what were the moments? What were the feelings that I felt defined the journey of my life?”

One such moment was at the Cannes premiere of The Usual Suspects, which threw him into an existential crisis from which he awoke in a hotel room many miles away, after praying for days to a God in whom he no longer believed.

The terror of finding himself catapulted into the celebrity stratosphere chimed with a conversation he recalled with Richard Burton from years earlier on the set of a starry television miniseries about the composer Richard Wagner. Byrne – an unknown, fished off the dole to deliver “10 lines in six countries” as the composer’s despised patron – had suffered the indignity of a cut lip when a makeup assistant attempted to adjust his glued-on moustache on board a rowing-boat. “‘Hey lippy,’ said Burton, afterwards, ‘come and have a drink’”.

Fame, Burton told him, doesn’t change who you are. It changes others. “He was talking about the existential malaise of success, what it means that you come to the brink, and there’s nothing but this huge cliff that brings you to nowhere,” says Byrne now.

A less promising encounter with Laurence Olivier on the same set, when Byrne accosted the actor, unaware that he was trying to memorise his lines, led to another piece of wisdom that he has carried with him through his life. In apology for his brusque brush-off, Olivier sent him a note quoting lines from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 60, about minutes hastening to their end, “He was telling me about time. And of course, now I’m much more conscious of what he was talking about. As Beckett knew, how foolish it is to try to mark time, when time has no mercy whatsoever.”

Though he has been in the US longer than he ever lived in Ireland, he says “I’ve never belonged here”. He spent several years in Hollywood, “and while it was lovely to reach out the window and pick an orange off a tree, and that every day the sun was shining, after a while that became suffocating, because there was no sense of time, and all anybody ever talked about was movies.”

He didn’t feel at home in New York, either. “There’s such an emphasis in America on happiness,” he grumbles, “that the entire society feels sometimes to me has gone completely inward, and is fixated now on the self, and on all these billions of dollars of self-help books. And that’s one of the things that Beckett was talking about. He said, you can imagine that you’re part of the world, and you are up to a certain point. But essentially, you are alone. But the answer isn’t in self-help books. The answer is in facing, as he did, the reality of life as it is, not how we would want it to be.”

In Maine, where he now lives with his wife Hannah Beth King, and their daughter, among fields that remind him of the rolling countryside of his youth, he is happy to report that nobody is involved in films. “People fish for lobster, and they make tables. I can live a very peaceful life here.” His relationship with acting is itself ambivalent. “It reminds me a little of what somebody once said about Columbus: when he started out, he didn’t know where he was going. When he got there, he didn’t know where he was, and when he came back, he didn’t know where he had been.”

But there’s a strong sense as he speaks that his relationship with Beckett is not over; is it possible, now that the dance of filming is over, that he is thinking of taking it into his own hands – perhaps into another one-man show? “Yes”, he says, “I did think about that. Then I lay down again, and I dozed off. But it’s an interesting idea. And if it does happen, I blame you.”

I promise him that I’ll be there on the first night with a bunch of wilting roses. “You might be the only person in the audience,” he replies, striking the funny side of morose with the timing of a natural-born Beckettian.

Dance First premieres at the San Sebastian film festival on 29 and 30 September, is in UK cinemas in November, on Sky Cinema in December and on Sky Arts in 2024

This article was amended on 22 September 2023 to remove an inaccurate description of the nationality and occupation of Hannah Beth King. In addition, the quote from Waiting for Godot, “Perhaps he could dance first and think afterwards”, is not said about Godot, but refers to Lucky. This has been amended.