Forty years ago, during the baking “long hot summer” immortalised by the Style Council’s song of the same name, my teenage body started to undergo a mysterious, unwelcome and life-upending transformation. I’d just finished my O-levels: as a treat my mother took me to Paris for a holiday.

One morning during our trip, I couldn’t get out of bed. My body felt as if it were pinned to the mattress by lead weights. There was also an unusual swelling forming at the front of my neck. My mother was concerned, and when the fatigue didn’t pass on our return home to Sheffield, she took me to the GP for a blood test.

Thyroid issues ran in the family; this was noted and checked out, but we were told that the test results were normal. By this time, it was autumn and I had started at a local comprehensive for sixth form. I began to make friends and enjoy the freedoms of sixth form – including spending Friday nights illicitly ordering half a cider and black at one of the many pubs on Sheffield’s West Street, and dancing at the legendary Limit nightclub.

But the tiredness increased and I was putting on weight, too. A lot of weight. From being slight, scrawny and always picking at my food, my appetite had grown colossal. By spring the following year I had gained five stone, was constantly breathless and falling asleep in class, with a rapid heartbeat, gripped by the fear of what, exactly, was waging war on my body. And that unnerving bulge in my neck was getting bigger.

Finally we went back to the doctor, where it was discovered that the blood tests I took six months earlier hadn’t been “normal” at all. Placed under the care of an endocrinology consultant, Graves’ disease, which causes hyperthyroidism, was diagnosed and I began to take daily medication.

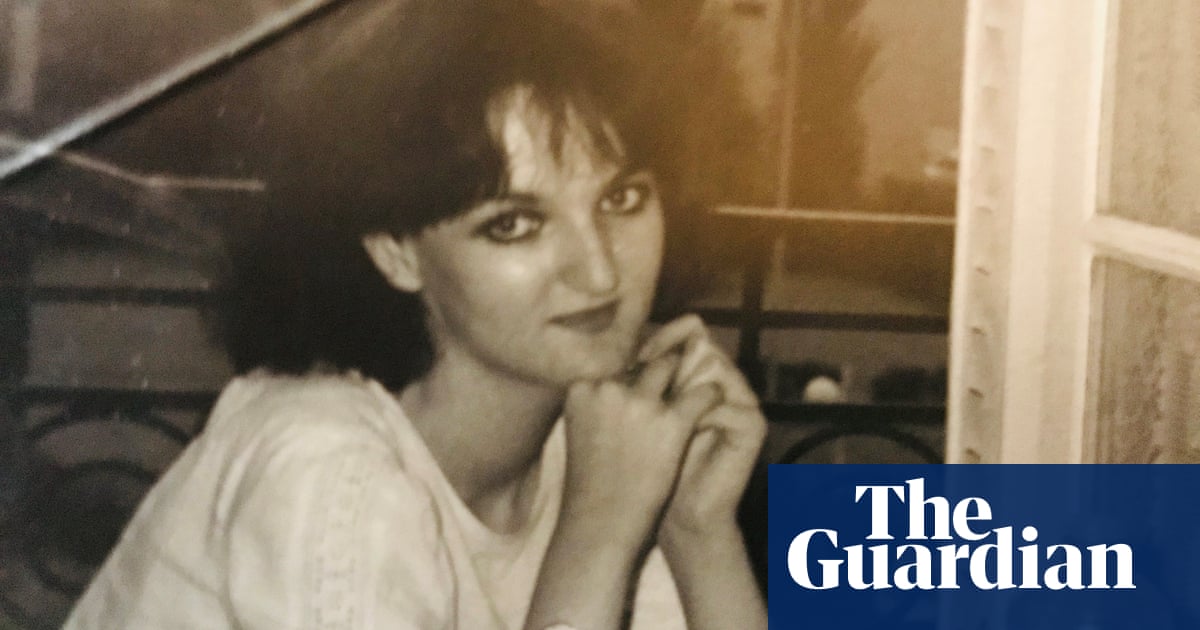

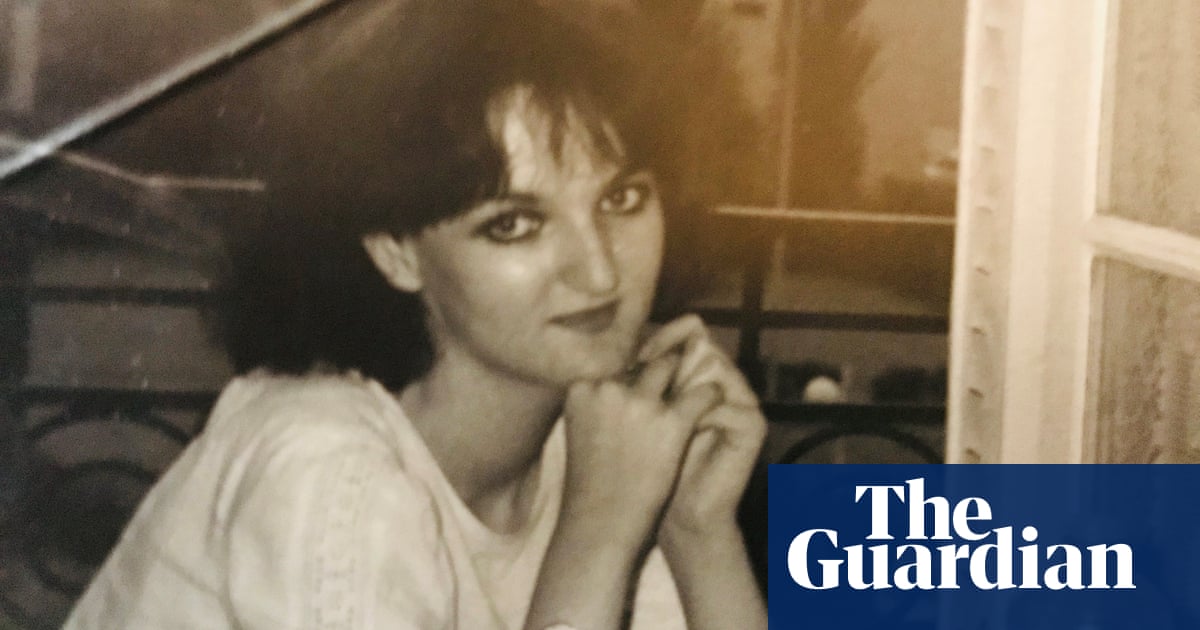

Each week I would attend a clinic where the evidence of what was known locally as “Derbyshire neck” (an enlarged goitre, the medical term for that lump at the front of my neck) was all around me. But despite losing weight as quickly as I had gained it, my year of bodily trauma left psychological as well as physical scars. Hating my appearance and now underweight again, I hacked off my hair and shrouded my form in oversized cardigans and voluminous dresses, even as my friends revelled in figure-hugging clothes. And while I longed to progress beyond vivid imagination to actual sexual experience, I despaired of anyone ever looking at me with desire.

Although the tablets kept the thyroid in check, they were only temporary: I would have to have an operation to remove most of the gland if I wanted a chance to function properly. By now I had failed my A-levels, having missed a lot of school and fallen behind my peers. The operation itself was not without complication – an unknown allergy to the anaesthetic almost finished me off. Yet in the long-term it saved my life: I would retake my exams and go on to university, although it would be years before I would feel confident or even comfortable in my body. It had let me down and I did not have any faith in its capacity not to do so again.

Because I had been informed that infertility was likely, my newfound sex life led to an unexpected pregnancy before I was ready for a baby. Much later, in my early 40s, I was diagnosed with a related autoimmune disease, the cause of repeated miscarriages in my 30s. Today, with the acceleration of age and the passing of years, I try to be more accepting of what I consider to be my body’s idiosyncrasies. There were occasions during that long-ago summer when I feared I would never get past adolescence; now I’m simply grateful to have made it this far.

The Stirrings: A Memoir in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in hardback, £16.99