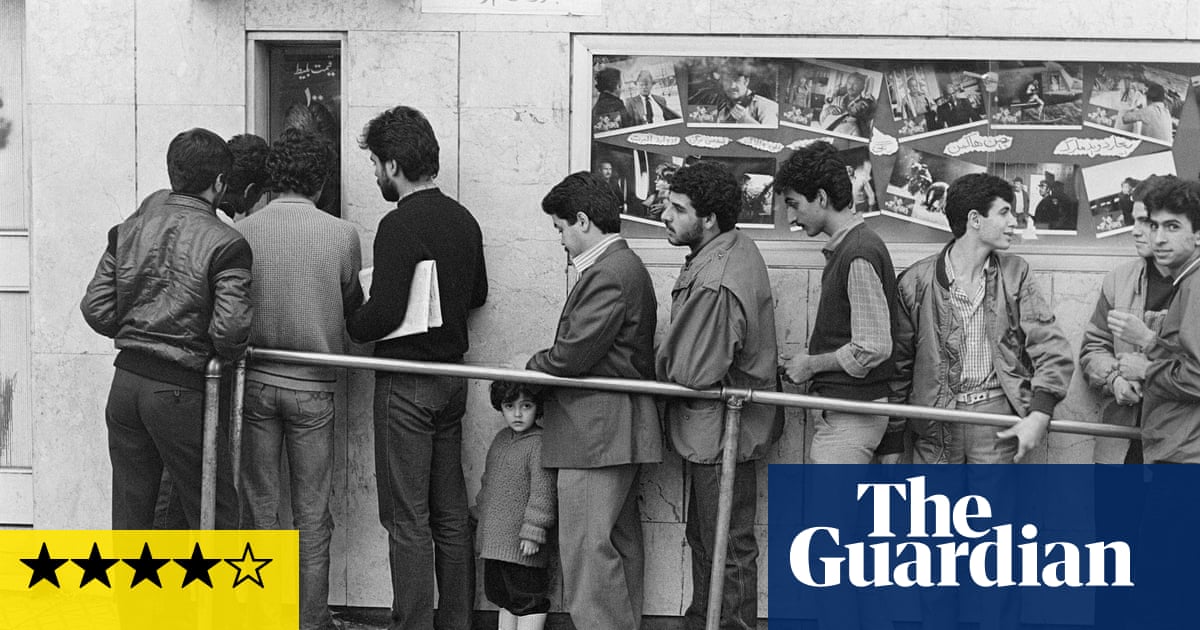

Passion for movies has hardly ever been more political than in Iran. Over the past century, drastic political change in certain countries has split the personality of the country’s film culture into two distinct halves. Usually, the new ideology ostracised and undermined the one that it had displaced. But in scarcely any other country has extreme change – a revolution – worked to make access to the past virtually impossible. The Islamic regime in Iran made watching any type of film outside strictly defined codes an illegal activity; doing so shunted the act of loving cinema into counterculture.

The regime’s aim, though never explicitly pronounced, was to destroy images of alternative realities and worlds. It is not yet clear how many films went up in smoke during the film incineration campaign of the early 1980s, a tragic episode still denied by the regime. This is the point when cinephilia became a hazardous occupation.

What the regime underestimated was the power of memory to piece together the fragments of film culture. Films were discussed but could not be seen. My father used to recount their plotlines as bedtime stories. Later, when I managed to see some of them, the version I had imagined was better.

The rich and diverse film culture of Iran continued to live on miraculously through the underground circulation of bootleg copies of films, old and new. Families and friends gathered to watch banned films, the closest they could get to reliving the collective experience they had taken for granted. But there were people for whom a memory was not enough.

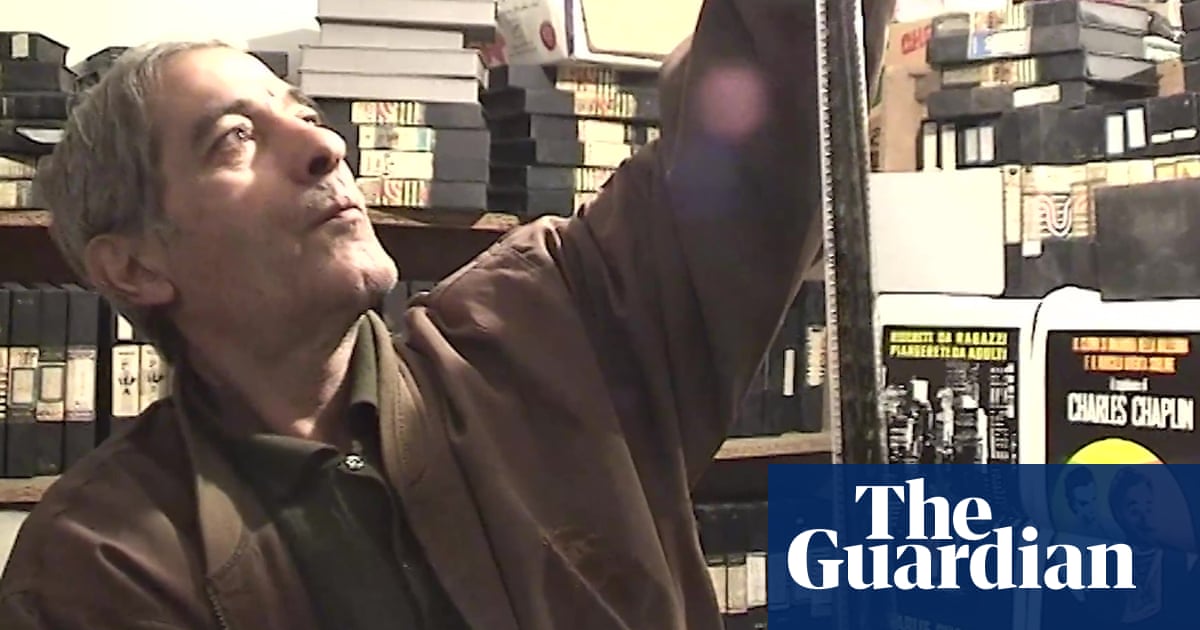

Ahmad Jorghanian was a legend who had organised film screenings at universities before the revolution, setting up a one-man operation to circulate arthouse films and major classics. To some, he was an opportunist but to many, a man totally immersed in cinema, and perhaps because of that, cut off from any other reality.

Having started collecting 35mm prints in the 1960s, by the time of the 1979 revolution he had on his hands thousands of films that all of a sudden were illegal possessions. Forced to go underground, he famously saved films from destruction for commercial and later ideological reasons.

Prior to the revolution, due to the cost of shipping them back to their western distributors, prints were crudely destroyed, chopped up with an axe. Jorghanian used every possible means to salvage the titles that he knew were under threat, secretly infiltrating storage houses and swapping prints of his favourite classics by Nicholas Ray or John Huston with disposable prints. The next day, unbeknown to the officials, the print of some insignificant film was being guillotined so Johnny Guitar could live on.

After the revolution, however, he faced a more brutal struggle. Deeming cinema a decadent art, the new regime aimed for the root of that presumed decadence: the 35mm film prints. Jorghanian started collecting films from distribution companies and production studios whose fearful owners, sensing potential trouble, were getting rid of their products. This 35mm Robin Hood grabbed what he could and hid his booty in the outskirts of Tehran, just as Henri Langlois did during the second world war occupation of France.

I first heard of the elusive Jorghanian in the mid-1990s and chased him as though he were Harry Lime in The Third Man. When I eventually found him and gained his trust, he took me to his secret vaults, often derelict basements of the old buildings in downtown Tehran. Shabby staircases led me down to a world where dreams were made. And they were made of celluloid.

Countless numbers of films were piled up. Gems from the entire history of cinema were there, sometimes in pristine conditions, very often battered and scratchy. He also had a priceless collection of thousands of original movie posters from the silent era through to 1979, an art collection that could not be put on public display.

Ahmad told me stories about his brief, if painful, prison stints. The first one was in 1983 when cinema was nationalised and the grip of the new regime on culture became total. He was arrested and tortured to reveal the hiding place of his films. Cinema was his idea of freedom, so when asked to give up his collection in exchange for release from prison, he faced the biggest dilemma of his life. He fooled them by revealing only one of his multiple storage locations, in the process losing hundreds of films. When released, he continued to safeguard what he had with even more determination. I have never seen fetishism and obsessive cinephilia morph with such intensity into a type of cultural resistance.

When some of that early revolutionary fervour died down, and certain cultural activities started to be tolerated again, he came out of hiatus and decided to loan out films again. It was never easy though. If a film was to be shown in public, certain scenes, including sex or even kissing, had to be removed. That kept Jorghanian on his toes. He cautiously let me screen his classics in semi-official or unofficial film clubs. It was so thrilling that often instead of watching the films I looked at the people who were watching them.

A generation learned their film history through Jorghanian’s prints. He died unexpectedly in 2014. His treasure, and what happened to it, became the subject of another legend that I am still trying to unravel. We often rightly celebrate people like Langlois in France, Ernest Lindgren in Britain, and PK Nair in India for their remarkable efforts to preserve film heritage. But we need to open a new chapter about those who kept the flame of cinema burning in the heart of tyranny. Ahmad proved that viewing and loving films could be a subversive act.