No one knows exactly how many south Asian miniature paintings are held in public and private collections in the UK, but Hammad Nasar, co-curator of a new exhibition at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, estimates it is at least 100,000. “As a sort of a thought exercise: imagine if there were 20,000 works by, say, Turner sitting in museums in Lahore or New Delhi,” he says. “What would that mean? And to whom?”

Beyond the Page will feature more than 170 artworks, including miniature paintings going back to the mid-16th century and the responses of 20th- and 21st-century artists – from south Asia and beyond – to these works, and to the form in general. Not that “miniature” is a “terribly agreed term”, says Nasar. “It’s a bit like when people say ‘the Middle East’: the middle of where? East of what?” While the works are generally small, “they don’t need to be the size of your thumbnail. They more share an approach to materials, a rigour of application and a kind of intimacy of encounter, no matter what the scale.”

First emerging about 1200 to illustrate Buddhist and Jain texts, miniature paintings went on to depict secular as well as religious subjects – domestic, courtly and ceremonial moments. The works tend to be small because they were usually bound together, making a hybrid form of art and book. “The first audience wasn’t people filing past museum walls,” says Nasar, “instead they were gathered together, maybe after dinner, and the works would be passed from one to another, held in people’s hands and brought close to their eyes to better see the intricate details. It’s that kind of intimacy artists are still attracted to.”

The works on display have been imported to the UK for more than 400 years, acquired through gifts, purchases, commissions and less scrupulous methods. There is even an important branch of miniatures called the Company School of painting, in which colonial patrons commissioned local artists to capture themselves, their families and their surroundings, resulting in a remarkable record of the British in India.

But the traffic has not been entirely one way. In the 1960s, artists Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh studied at the Royal College of Art in London and, independently, found themselves walking through the miniatures collection of the V&A on their way to classes. “Of course, they were already familiar with miniature paintings,” says Nasar, “but the intensity of these everyday encounters, and the opportunity to engage with scholars, saw them look anew at the work and expand their visions. They returned home to arguably the most important art schools in Pakistan and India respectively, and their influence over artists and institutions is still being felt today.”

Over the centuries, the miniature has symbolised many things: the vast wealth and power of those who commissioned the work; the impact of colonialism; and also of anti-colonialism, when adopted by local artists as an indigenous artform.

“It can symbolise different things, depending on which century and in which place you happen to be,” says Nasar. “The miniature is one of those Rorschach tests that allows different people to see different things.”

Small wonders: five key works from Beyond the Page

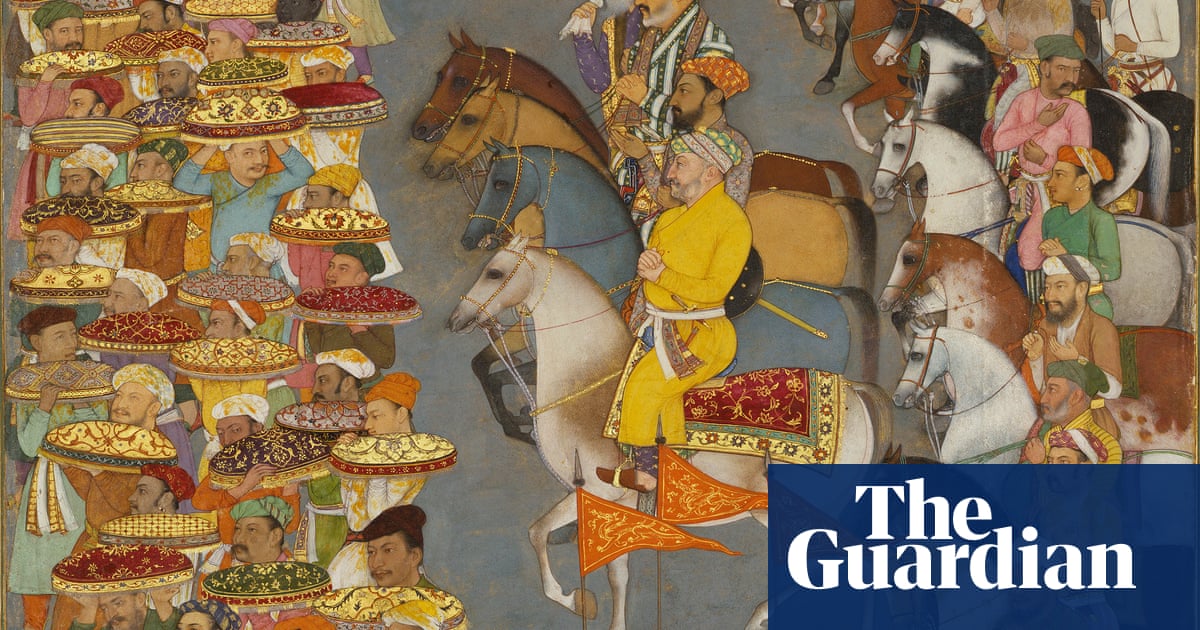

The delivery of presents for Prince Dara Shikoh’s wedding in December 1632, c 1640 (main image)

This image from the Padshahnama, a history of a Mughal emperor, was presented to George III and is still held in the Royal Collection. It depicts a lavish wedding complete with splashes of bright yellow turmeric used in wedding rituals to this day. Its use as the cover for a 1997 edition of the Padshahnama saw it become an important source for south Asian artists.

Hamra Abbas – All Rights Reserved, 2004

This is one of four digital prints responding to the image of Prince Dara Shikoh’s wedding. Abbas, in a nod to the painting’s physical removal from India, here removes the gifts from the wedding guests. In another panel she depicts only the gifts, and in the other two she reproduces the copyright terms and title page from an art catalogue, underlying not just how important the actual objects are, but also how access to them is contained.

Dip Chand – Portrait of William Fullerton, c 1764

The Company School of painting has been described as the Instagram of its day. Here, Fullerton, a Scottish doctor who had made his fortune in India, is seen adopting an aristocratic Bengali lifestyle while retaining a British sense of dress. Company School artists were often among the finest of the time, employed by the British after the decline of local royal patronage.

Nusra Latif Qureshi – Did You Come Here to Find History?, 2009

These digital portraits, on a nine metre-long film scroll, include both the artist as well as historical figures. The transparency of the material emphasises the palimpsestic nature of both art and history.

Women in outdoor cloaks, c 1720–40

This work first appeared in book form, as a copy of an image on the reverse painted in the century before. Patrons would encourage their artists to copy older work, as well as alter the presentation of the art, in an ongoing process of curation, addition and subtraction.